Capital as Power

Toward a New Cosmology of Capitalism

Shimshon Bichler & Jonathan Nitzan

Transcript of a presentation at New Marxian Times | The Seventh International Rethinking Marxism Conference

University of Massachusetts, Amherst | November 5-8, 2009

Introduction

Let’s begin with cosmology.

• As Marx tells us, the capitalist regime is inextricably bound up with its theories and ideologies.

• These theories and ideologies, first articulated by classical political economy, are much more than a passive attempt to explain, justify and critique the so-called “economic system.”

• Instead, they constitute an entire cosmology: a system of thinking that is both active and totalizing.

• In ancient Greek, Kosmeo has an active connotation: it means “to order” and “to organize,” and political economy does precisely that:

• It explains, justifies and critiques the world; but it also actively makes this world in the first place.

• And it pertains not to the narrow “economy” as such, but to the entire social order, as well as to the natural universe in which this social order is embedded.

The purpose of my presentation is to outline an alternative cosmology – to outline the beginning of a totally different framework for understanding capitalism.

• Of course, to suggest an alternative, we first need to know the thing that we contest and seek to replace.

• Therefore, I’ll begin my talk by spelling out what Shimshon and I consider as the hallmarks of the present capitalist cosmology.

• Following this initial step, I’ll enumerate the reasons why, over the past century, this cosmology gradually disintegrated – to the point of being unable to understand and recreate its world.

• Finally, I’ll articulate some of the key themes of our own theory – the theory of “capital as power.”

Part 1: The Capitalist Cosmology

Political economy, liberal as well as Marxist, stands on three key foundations that I’ll first list and then unzip.

• The first foundation is a separation between “economics” and “politics.”

• The second foundation is a Galilean/Cartesian/Newtonian mechanical understanding of the “economy.”

• And the third foundation is a value theory that breaks the “economy” into two spheres – “real” and “nominal” – and that uses the quantities of the “real” sphere in order to explain the appearances of the “nominal” one.

Now, let’s examine each of these foundations more closely, beginning with the first one – the separation of “economics” and “politics.”

• During the 13th and 14th centuries, there emerged in the city states of Italy and the Low Countries an alternative to the rural feudal state.

• This alternative was the urban order of the capitalist Bourg.

• The rulers of the Bourg were the capitalists.

• They were the owners of money, trading houses and ships; they were the managers of industry; they were the enterprising pursuers of new social technologies and the seekers of innovative methods of production.

• These early capitalists offered an entirely new way of organizing society.

• Instead of the vertical feudal order, in which privilege and income were obtained by force and sanctified by religion, they brought a flat civil order, an order in which privilege and income derived from rational productivity.

• Instead of the closed loop of agricultural redistribution by confiscation, they promised open-ended industrial growth.

• Instead of ignorance, they brought progress and knowledge.

• Instead of subservience, they offered opportunity.

• Theirs was the future regime of capital, an “economic” order based on an endless cycle of production and consumption and the ever-growing accumulation of money.

Initially, the Bourg was subservient to the feudal order in which it emerged, but that status gradually changed.

• The Bourgs began to demand and obtain libertates – that is, differential exceptions from feudal penalties, taxes and levies.

• The bourgeoisie recognized the legitimacy of feudal “politics,” particularly in matters of religion and war.

• But it demanded that this “politics” not impinge on its urban “economy.”

• This early class struggle, the power conflict between the declining nobility and the rising bourgeoisie, is the origin of what we now consider as the separation of “economics” and “politics.”

The features of this separation are worth summarizing, beginning with the liberal view.

• Over the past half-millennium, liberals have grown accustomed to classifying production, technology, trade, income and profit as aspects of the “economy.”

• By contrast, entities like state, law, army and violence are classified as belonging to “politics.”

• The economy is taken to be the productive source:

• It is the realm of individual freedom, rationality, frugality and dynamism.

• It creates output, raises consumption and moves society forward.

• By contrast, politics is conceived as coercive-collective; it is corrupt, wasteful and conservative; it is a parasitical sphere that latches onto to the economy, taxing it and intervening in its operations.

• Ideally, the economy should be left on its own: laissez faire politics would produce the most efficient economic outcome.

• But, then, in practice this is never the case: political intervention, we are told, constantly distorts economics, undermining its efficient operation.

• The liberal equation, then, is simple: the best society is one with the most “economics” and the least “politics.”

The Marxist view of this separation is different, but not entirely.

• For Marx, the liberal dichotomy between civil society and state is a misleading ideal, if not an outright self-deception.

• The political-legal structure, he says, is not separate from but integral to the material economy.

• The bureaucracy of the state legitimizes capital; it gives its accumulation a universal form; it maintains the overall framework of the capitalist system.

• However, when Marx comes to construct his own “capitalist system,” he retains the dual structure: there is a material economic base of exploitation, and that base is supported by state and legal institutions that rely on oppression.

Following the footsteps of his classical predecessors, particularly Smith and Ricardo, Marx, too, prioritized economics over politics.

• The productive sphere, and especially the labor process, he argued, is the engine of social development.

• This is where use value is created, where surplus value is generated, where capital is accumulated.

• Production is the fountainhead; it is the ultimate “source” from which the other spheres of society draw their energy – energy which they in turn use to help shape and sustain the sphere of production on which they so depend.

• And so, although for Marx capitalist economics and politics are deeply intertwined, their interaction is that of two conceptually distinct entities.

The second foundation of political economy is the Galilean/Cartesian/Newtonian model.

• The new capitalist order emerged hand-in-hand with a political/scientific revolution – a revolution that was marked by the mechanical worldview of Machiavelli, Kepler, Galileo, Descartes, Hobbes, Locke, Hume, Leibnitz and, most importantly, Newton.

• It is common to argue that political economists have borrowed their metaphors and methods from the natural sciences.

• But we should note that the opposite is equally true, if not more so; in other words, that the worldview of the scientists reflected their society.

Consider the following examples.

• Galileo and Newton were deeply inspired by Machiavelli’s Prince.

• The Prince relentlessly pursues secular power for the sake of secular power.

• His concern is not the general good, but order and stability.

• And he achieves his goals not with divine help, but through the systematic application of calculated rationality.

• Hobbes’ “mechanical human being” was modeled after Galileo’s pendulum, swinging between the quest for power on the one hand and the fear of death on the other; but, then, Galileo’s own mechanical cosmos was itself a reflection of a society increasingly pervaded by machines. . . .

• Newton could make up a world of independent bodies because he lived in a society that began to critique hierarchical power and praise and glorify individualism.

• He envisaged a liberal world in which every body was a lonely soul in the cosmos, inter-acting with but never imposing its will onto other bodies.

• There is no ultimate cause in Newton, only inter-dependence.

• Descartes could emphasize the immediacy of cause and effect – the leaves move only if the wind touches them – because he lived in a world that increasingly contested religious, church-invoked miracles that operated at a distance.

• Lavoisier was a royal tax farmer; he invented his law of conservation of matter while building a wall around Paris, seeking to create a “sealed container” within which he could capture the city’s mass of taxable income.

• Darwin’s “survival of the fittest” was modeled after Malthus’ population theory.

• And so on.

These examples shouldn’t surprise us.

• Human beings tend to impose on the cosmos the power structure that governs their own society.

• In other words, they tend to politicize nature.

• In “archaic” societies – for instance, those of nomads – the gods are usually numerous, relatively equal and hardly omnipotent.

• Hierarchical, statist societies tend to impose a pantheon of gods.

• And absolute rule tends to insist on a single god and a monotheistic religion.

• In each case, the forces that make up nature reflect – and in turn are reflected in – the forces that shape society.

Capitalism is no exception to this historical rule.

• Consider the mechanical worldview.

• The liberal God is nothing but absolute rationality, or natural law.

• The language of God is mathematical, and therefore the structure of the universe is numerical.

• The universe that God created is flat: it is filled with numerous bodies that are not subservient and dependent, but free and interdependent.

• These bodies are propelled not by differential obligations, but by the universal force of gravity.

• They are attracted and repelled to one another not by the will of the Almighty, but through the interaction of force and counterforce.

• And, finally, they are ordered not through decree, but through the invisible power of equilibrating inertia.

This flat universe mirrors the flat ideals of liberal society.

• A liberal society consists of equally small actors, or particles, none of which is large enough to affect the other particles/actors.

• These particles/actors are energized not by patriarchal obligations, but by scarcity – the gravitational force of the social universe.

• They are attracted to and repelled from one another not by feudal obligations, but through the universal functions of demand and supply.

• And they obey not a hierarchical rule, but the equilibrating forces of the invisible hand of perfect competition.

The third foundation of political economy is the economic duality of “real” and “nominal” and the value theory that links them.

• Capitalism is a system of commodities, and as such it is denominated in the universal units of price.

• To understand the nature and dynamics of this architecture, we need to understand prices, and that is why both liberal and Marxian political economies are founded on theories of value: the utility theory of value and the labor theory of value.

Value theories begin by splitting the “economy” itself into two parallel, quantitative spheres: “real” and “nominal.”

• The key is the “real” sphere.

• This is where production and consumption take place, where supply and demand interact, where utility and productivity are determined, where power and equilibrium compete, where well-being and exploitation take place, where surplus value and profit are generated.

Now, on the face of it, it seems difficult to quantify the “real” sphere.

• Why is that?

• Because the entities of this sphere are qualitatively different, and that qualitative difference makes them incommensurate.

• But this problem, say the economists, is more apparent the real.

• Physicists and chemists express all measurements in terms of five fundamental quantities: distance, time, mass, electrical charge and heat.

• In this way, velocity can be defined as distance divided by time.

• Acceleration is the time derivative of velocity.

• Force is mass times acceleration, etc.

• And according to themselves, economists are able to do the very same thing.

• They, too, have fundamental quantities: the fundamental quantity of the liberal universe is the util, and the fundamental quantity of the Marxist universe is socially necessary abstract labor.

• With these fundamental quantities, every “real” entity – from concrete labor, to the full range of commodities, to the capital stock – can be reduced to and expressed in the very same units.

• And with “real” entities all having a common denominator, the system can be fully specified.

Now, parallel to the “real” sphere stands the “nominal” world of money and prices.

• This sphere constitutes the immediate appearance of the commodity system.

• But that is merely a derived appearance.

• In fact, the “nominal” sphere is nothing but a giant, symbolic mirror.

• It is a parallel arena, an arena whose universal dollar magnitudes merely reflect – sometimes accurately, sometimes not – the underlying “real” util and labor quantities of production and consumption.

So we have a quantitative correspondence.

• The “nominal” sphere of prices reflects the “real” sphere of production.

• And the purpose of value theory is to explain this reflection/correspondence.

How does value theory sort out this correspondence?

• In the liberal version, the double-sided economy is assumed to be contained in a Newtonian-like space: a container that comes complete with its own invisible laws – or “functions” – that equilibrate quantities and prices.

• The Marxist version is very different, in that it emphasizes not equilibrium and harmony, but the conflictual/dialectical engine of the economy.

• However, here, too, there is a clear bifurcation between the “real” and the “nominal.”

• And here, too, there is an assumed set of rules – the historical laws of motion – that govern the long-term interaction of these two spheres.

Now, the role of the political economist is merely to “discover” these principles, or laws.

• The method of discovery builds on the research paradigm of Galileo, Descartes and Newton on the one hand, and on the application of probability and statistics on the other.

• In this method, discovery takes place through the fusion of experimentation and generalization – a method that liberals carry through “testing” and “prediction” and that Marxists undertake through the “dialectics” of theory and praxis.

Finally, unlike economics, politics doesn’t have its own intrinsic rules.

• This difference has two important consequences.

• In the liberal case, the self-optimizing nature of the economy means that political intervention can only lead to sub-optimal outcomes.

• In the Marxist case, politics and state are inextricably bound up with production and the economy.

• However, since politics and state in the Marxist case have no rules of their own, they have to derive their logic from the economy – either strictly as argued by “structuralists,” or loosely as argued by “instrumentalists.”

To sum up, then, the cosmology of capitalism is built on three key foundations.

• The first foundation is the separation between “economics” and “politics.” The economy is governed by its own laws, whereas politics is either derived from these economic laws or distorts them.

• The second foundation is a mechanical view of the economy itself, a view based on action and reaction, flat functions and the self-regulating forces of motion and equilibrium. The role of the political economist is merely to discover these mechanical laws.

• The third foundation is the bifurcation of the economy itself into two quantitative spheres – “real” and “nominal.” The “real” sphere is enumerated in material units of consumption and production (utils or socially necessary abstract labor). The “nominal” sphere is counted in money prices – but these prices merely mirror the quantities of the “real” sphere. And the role of value theory is to explain this correspondence.

Part 2: The Rise of Power and the Demise of Political Economy

Now, these foundations of the capitalist cosmology started to disintegrate in the second half of the 19th century.

• The key reason for this disintegration was the very victory of capitalism.

• Note that political economy differed from all earlier cosmologies in that it was the first to substitute secular for religious force.

• But this secular force was assumed to be heteronomous; i.e., it was an objective entity, external to society.

The victory of capitalism changed this perception.

• With the feudal order finally giving way to the capitalist regime, it became increasingly apparent that force is imposed not from without, but from within.

• In other words, instead of heteronomous force, there emerged autonomous power, and this shift changed everything:

• With autonomous power, the dualities of economics/politics, the separation of real/nominal, and the mechanical worldview of political economy were all seriously undermined.

• With these categories undermined, the presumed automaticity of political economy no longer held true.

• And with automaticity gone, political economy ceased being a science.

The recognition of power was affected by four important developments.

• The first development was the emergence of totally new units.

• By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the notion of atomistic interdependent actors had declined in the face of large hierarchical organizations – from big business and large unions to big government and large NGOs.

• The second development was the emergence of many new phenomena, phenomena that were largely unknown to the classical political economists.

• By the beginning of the 20th century, “total war” and a so-called “permanent war economy” had been established as salient features of modern capitalism, features that seemed no less important than production and consumption.

• Governments started to actively engage in massive industrial and macro stabilization policies, policies that completely upset the presumed automaticity of the so-called “economic sphere.”

• Capitalists incorporated their businesses and in the process bureaucratized and socialized what had previously been considered “private” accumulation.

• The singular act of labor grew not simpler and more homogenous, but ever more complex, and workers no longer lived at subsistence. There emerged a “labor aristocracy”; workers’ standard of living in the main capitalist countries soared; and with rising disposable income, issues of culture grew in importance relative to work.

• Finally, the nominal processes of inflation and finance assumed a “life of their own,” following a trajectory that no longer seemed to reflect the so-called “real” sector.

• The third development was the emergence of totally new concepts.

• With the rise of fascism and Nazism, the primacy of class and production was challenged by a new emphasis on “masses,” “power,” “state,” “bureaucracy,” “elite” and, eventually, “social systems.”

• Fourth and finally, the objective/mechanical cosmology of the first political-scientific revolution was challenged by uncertainty, relativity and the entanglement of subject and object.

• Science was increasingly challenged by anti-scientific vitalism and postism.

• Francis Bacon was pronounced dead, and ignorance has become strength.

The combined result of these developments was a growing divergence between universality and fracture.

• On the one hand, the regime of capital has become the most universal system ever to organize society. Its rule spread to every corner of the world and incorporated more and more aspects of human life.

• On the other hand, political economy – the cosmology of that order – was fatally fractured. In the place of what was once an integrated science of society, there emerged a collection of partial and exclusionary social “disciplines.”

The mainstream liberal study of society was split into numerous “social sciences.”

• These social sciences – the “disciplines” of economics, political science, sociology, anthropology, psychology, and now also culture, gender and other such offshoots – are each treated as a “closed system.”

• They come with their own unique jargon, proprietary principles, and a bureaucratic-academic hierarchy that excludes outsiders and wards off competitors.

But this fracturing didn’t save economics.

• The rise of autonomous power destroyed the fundamental quantities of economics.

• First and foremost, it made it patently clear that utils and abstract labor were both logically impossible and empirically unknowable.

• And, indeed, no liberal economist has ever been able to measure the util content, and no Marxist has ever been able to calculate the abstract labor content, of commodities.

• This inability is existential.

• With no fundamental quantities, value theory becomes impossible.

• And with no value theory, economics disintegrates.

The neoclassicists responded to this threat by turning their economics into a null domain.

• In order to avoid the destructive effects of power, they have withdrawn into the heavily subsidized fantasy of perfectly competitive equilibrium, where everything still works as it should.

• To achieve this end, though, they had to exclude from their domain almost every meaningful phenomenon – and they have done their job so thoroughly that their theory now perfectly explains next to nothing.

• And when the reality still clashes with the theory – which is nearly always the case – the solution is to blame it all on either micro “distortions” and “imperfections” or macro “interventions” and “shocks.”

Unlike the neoclassicists, Marxists have addressed power head on – but this trajectory destroyed the original unity of Marx’s theory.

• To recognize power meant to abandon the labor theory of value.

• But since Marxists never came up with another theory of value, their worldview lost its main unifying force.

• The net result was a neo-Marxist fracture.

• The neo-Marxism of today consists of three sub-disciplines, each with its own categories, logic and bureaucratic demarcations.

• The first sub-discipline is neo-Marxist economics, based on a juxtaposition of “monopoly capital” and permanent “government intervention.”

• The second sub-discipline comprises neo-Marxist critiques of capitalist culture.

• And the third sub-discipline consists of neo-Marxist theories of the state.

Now, I should stress here that both Marx and the neo-Marxists have had very meaningful things to say about the world.

• Let me list a few.

• The comprehensive view of human history – an approach that negates and supersedes the particular histories dictated by elites.

• The notion that ideas are dialectically embedded in their concrete material history.

• The link between theory and praxis.

• The notion of capitalism as a totalizing political-power regime.

• The universalizing-globalizing tendencies of this regime.

• The dialectics of the class struggle.

• The fight against exploitation, oppression and imperial rule.

• The emphasis on autonomy and freedom as the motivating force of human development.

• These ideas are all indispensable.

• Moreover, the development of these ideas is deeply enfolded, to use David Bohm’s term, in the very history of the capitalist regime, and in that sense these ideas can never be discarded as “erroneous.”

But all of that still leaves the most important question unanswered.

• In the absence of a unifying value theory, there is no logically coherent and empirically meaningful way to explain the so-called “economic” accumulation of capital – let alone to account for how culture and the state presumably affect such accumulation.

• In other words, we have no explanation – and in fact no clear definition – for the most important process of all: the accumulation of capital.

Capitalism, though, remains a universalizing system, and a universalizing system calls for a universal theory.

• So maybe it’s time to stop the fracturing.

• We don’t need finer and finer nuances.

• We don’t need new sub-disciplines that then get connected through inter-disciplinary links.

• We don’t need imperfections and distortions to tell us why our theories do not work.

• What we do need is a radical Ctrl-Alt-Del.

• As Descartes tells us, to be radical means to go to the root, and the root of capitalism is the accumulation of capital.

• This, then, should be our new starting point.

Part 3: Toward a New Cosmology of Capitalism

In the remainder of my presentation, I’ll try to outline briefly some of the key elements of our own approach to capital.

• This outline isn’t comprehensive; it’s merely suggestive.

• It is meant simply to tickle your imagination, to lure you to the rest of our panels, and perhaps to give you a reason to read further.

Our starting point is power.

• We argue that capital is not what political economists say it is.

• Capital isn’t means of production; it isn’t the ability to produce hedonic pleasure; it isn’t a quantum of dead productive labor.

• Rather, capital is power, and only power.

Further, and more broadly, we argue that capitalism is not a mode of production or consumption, but a mode of power.

• Machines, technology, production and consumption of course are part of capitalism, and they certainly feature in accumulation.

• But the role of these entities in the process of accumulation – whatever that role may be – is significant only through the way they bear on power.

To explicate our argument, we begin with two related entities: prices and capitalization.

• Capitalism – as we already noted, and as both liberals and Marxists correctly recognize – is organized as a commodity system denominated in prices.

• Capitalism is particularly conducive to numerical organization because it is based on private ownership, and anything that can be privately owned can be priced.

• This feature means that, as private ownership spreads spatially and socially, price becomes the universal numerical unit through which the capitalist order is organized.

Now, the concrete pattern of this order is created through capitalization.

• Capitalization, to paraphrase physicist David Bohm, is the generative order of capitalism.

• It is the flexible/encompassing algorithm that creorders – or continuously creates the order of – capitalism.

What exactly is capitalization?

• Capitalization is a symbolic financial entity, a computational ritual that capitalists invoke when they exercise their power.

• As a technical procedure, capitalization is the discounting to present value of risk-adjusted expected future earnings.

• The principles of capitalization have had a long gestation period.

• They first emerge in the Italian Bourgs of the 14th century.

• They were systematically articulated about a century ago.

• And they became the all-dominant ritual of capitalism around the 1950s.

Now, as Ulf Martin will explain in his presentation later today, capitalization is an operational-computational symbol.

• Unlike ontological symbols, capitalization isn’t a passive representation of the world.

• Instead, it is an active, synthetic calculation.

• It is a symbol that human beings create and impose on the world – and in doing so, they shape the world in the image of their symbol.

Capitalists – as well as everyone else – are conditioned to think of capital as capitalization and nothing but capitalization.

• The ultimate issue here is not the particular entity that the capitalist owns, but the universal worth of that entity defined as a capitalized asset.

• Neoclassicists and Marxists recognize this symbolic creature – but given their view that capital is a “real” economic entity, they don’t quite know what to do with its symbolic counterpart.

• The neoclassicists bypass the impasse by saying that, in principle, capitalization is merely the image of “real” capital – although, in practice, this image gets distorted by unfortunate “market imperfections.”

• The Marxists approach the problem from the opposite direction.

• They begin by assuming that capitalization is entirely “fictitious” – and therefore unrelated to “real” capital.

• But then, in order to sustain their labor theory of value, they also insist that, occasionally, this “fiction” must crash into equality with “real” capital.

In our view, these attempts to make capitalization fit the box of “real” capital are exercises in futility.

• As we already saw, not only does “real” capital lack an objective quantity, but the very notion that there exists a capitalist “economy” distinct from “politics” is no longer defensible.

• And, indeed, capitalization is hardly limited to the so-called “economic” sphere.

• In principle, every stream of expected income is a candidate for capitalization.

• And since income streams are generated by social entities, processes, organizations and institutions, we end up with capitalization discounting not the so-called “sphere of economics,” but potentially every aspect of society.

• Human life, including its social habits and its genetic code, is routinely capitalized.

• Institutions – from education and entertainment to religion and the law – are habitually capitalized.

• Voluntary social networks, urban violence, civil war and international conflict are regularly capitalized.

• Even the environmental future of humanity is capitalized.

• Nothing escapes the eyes of the discounters: if it generates future income, it can be capitalized.

The encompassing nature of capitalization calls for an encompassing theory, and the unifying basis for such a theory, we argue, is power.

• The primacy of power is built right into the definition of private ownership.

• Note that the English word “private” comes from the Latin privatus, which means restricted, and from privare, which means to deprive.

• In this sense, private ownership is wholly and only an institution of exclusion, and institutional exclusion is a matter of organized power.

• Of course, exclusion does not have to be exercised: what matter here are the right to exclude and the ability to exact pecuniary terms for not exercising that right.

• This right and ability are the foundations of capital accumulation.

Capital, then, is nothing but organized power.

• This power has two sides: one qualitative, the other quantitative.

• The qualitative side comprises the institutions, processes and conflicts through which capitalists constantly creorder society, shaping and restricting its trajectory in order to extract their tributary income.

• The quantitative side is the process that integrates, reduces and distils these numerous qualitative processes down to the symbolic magnitude of capitalization.

Now, what is the object of capitalist power? How does it creorder society?

• The answer begins from a conceptual distinction between the creative/productive potential of society – the sphere that Thorstein Veblen called industry – and the realm of power that, in the capitalist epoch, takes the form of business.

• Using as a metaphor the concept of physicist Denis Gabor, we can think of the social process as a giant hologram, a space crisscrossed with incidental waves.

• Each social action – whether an act of industry or of business – is an event, an occurrence that generates vibrations throughout the social space.

• But there is a fundamental difference between the vibrations of industry and the vibrations of business.

• Industry, understood as the collective knowledge and creative effort of humanity, is inherently cooperative, integrated and synchronized. It operates best when its various events resonate with each other.

• Business, on the other hand, isn’t collective; it is private. And it works best through conflict.

• The goals of business are achieved through the threat and exercise of systemic prevention and restriction – that is, through strategic sabotage.

• The key object of this sabotage is the resonating pulses of industry – a resonance that business constantly upsets through built-in dissonance.

Let’s illustrate this interaction of business and industry with a simple example.

• Political economists, both mainstream and Marxist, postulate a positive relationship between production and profit.

• Capitalists, they argue, benefit from industrial activity – and, therefore, the more fully employed their equipment and workers are, the greater their profit.

• But if we think of capital as power, exercised through the strategic sabotage of industry by business, the relationship becomes non-monotonic and possibly inverse.

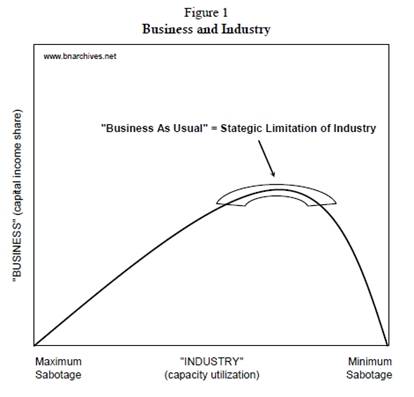

• This latter relationship is illustrated, hypothetically, in Figure 1.

• The chart contrasts and relates the utilization of industrial capacity, on the horizontal axis, with the capitalist share of income on the vertical axis.

• Now, up to a point, the two measures move together; after that point, the relationship becomes negative.

• The reason for this inversion is easy to explain by looking at extremes.

• If industry came to a complete standstill at the bottom left corner of the chart, capitalist earnings would be nil.

• But capitalist earnings also would be zero if industry always and everywhere operated at full socio-technological capacity – depicted by the bottom right corner of the chart.

• Under this latter scenario, industrial considerations rather than business decisions would be paramount, production would no longer need the consent of owners, and these owners would be unable to extract their tribute earnings.

• For owners of capital, then, the ideal Goldilocks condition lies somewhere in between.

• This condition is indicated by top of the arc in the chart, with high capitalist earnings being received in return for letting industry operate – though only at less than full potential.

Now, having laid out the theory, let’s look at the facts.

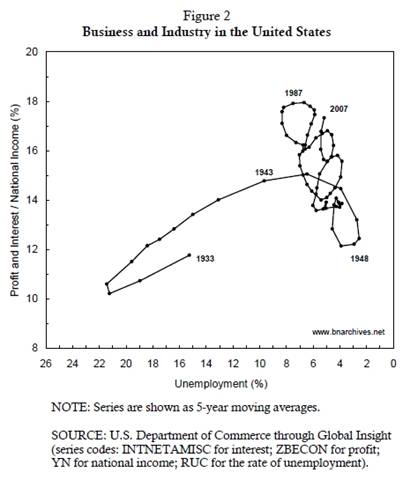

• Figure 2 shows this relationship for the United States since the 1930s.

• The horizontal axis approximates the degree of sabotage by using the official rate of unemployment, inverted (notice that unemployment begins with zero on the right, indicating no sabotage, and as it increases to the left so does sabotage).

• The vertical axis, as before, shows the share of capitalists in national income.

• And lo and behold, what we see is very close to the theoretical claims represented in Figure 1.

• The best position for capitalists is not when industry is fully employed, but when the unemployment rate is around 7 percent.

• In other words, “business as usual” and the so-called “natural rate of unemployment” are two sides of the same power process: a process in which business accumulates by strategically sabotaging industry.

Now, power is never absolute; it’s always relative.

• For this reason, both the quantitative and qualitative aspects of capital accumulation have to be assessed differentially – that is, relative to other capitals.

• Contrary to standard political economy, both liberal and Marxist, capitalists are driven not to maximize profit, but to “beat the average” and “exceed the normal rate of return.”

• Their entire existence is conditioned by the need to outperform, by the imperative of achieving not absolute accumulation, but differential accumulation.

• And that makes perfect sense.

• To beat the average means to accumulate faster than others; and since capital is power, capitalists who accumulate differentially increase their power.

Let’s illustrate this process with another example, taken from our work on the global political economy of the Middle East.

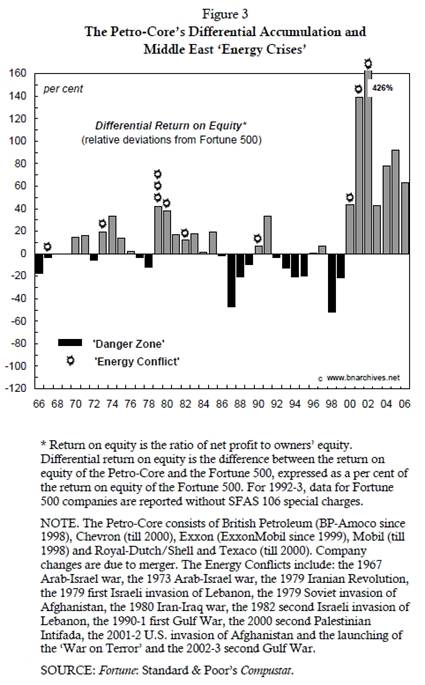

• Figure 3 shows the differential performance of the world’s six leading oil companies relative to the Fortune 500 benchmark.

• Each bar in the chart measures the extent to which the oil companies’ rate of return on equity exceeded or fell short of the Fortune 500 average.

• The gray bars show positive differential accumulation – i.e. the percent by which the oil companies exceeded the Fortune 500 average.

• The black bars show negative differential accumulation – that is, the percent by which the oil companies trailed the average.

• Finally, the explosion signs in the chart show the occurrences of “Energy Conflicts” – that is, regional energy-related wars.

Now, conventional economics has no interest in the differential profits of the oil companies, and it certainly has nothing to say about the relationship between these differential profits and regional wars.

• Differential profit is perhaps of some interest to financial analysts.

• Middle-East wars are the business of international relations experts and security analysts.

• And since each of the two phenomena belongs to a completely separate realm of society and a distinct academic “discipline,” no one has ever thought of relating them in the first place.

• And yet, as it turns out, these phenomena are not simply “related.”

• In fact, they could be thought of as two sides of the very same process – namely, the global accumulation of capital as power.

We started to study this subject when we were still graduate students, back in the late 1980s, and we’ve published quite a bit about it since then.

• This research opened our eyes – first, to the encompassing nature of capital; and second, to the insight that one can gain from analyzing its accumulation as a power process.

• Notice the three remarkable relationships depicted in the chart.

• First, every energy conflict was preceded by the large oil companies trailing the average. In other words, for an energy conflict to erupt, the oil companies first had to differentially decumulate – a most unusual prerequisite from the viewpoint of any social science.

• Second, every energy conflict was followed by the oil companies beating the average. In other words, war and conflict in the region – processes that social scientists customarily blame for “distorting” the aggregate economy – have served the differential interest of certain key firms at the expense of other key firms.

• Third and finally, with one exception, in 1996-7, the oil companies never managed to beat the average without there first being an energy conflict in the region. In other words, the differential performance of the oil companies depended not on production, but on the most extreme form of sabotage: war.

Needless to say, these relationships, and the conclusions they give rise to, are nothing short of remarkable.

• First, the likelihood that all three patterns are the consequence of statistical fluke is negligible. In other words, there must be something very substantive behind the connection of Middle East wars and global differential profits.

• Second, these relationships seamlessly fuse quality and quantity. In our research on the subject, we show how the qualitative aspects of international relations, superpower confrontation, regional conflicts and the activity of the oil companies on the one hand, both explain and are explained by the quantitative global process of capital accumulation on the other.

• And, third, all three relationships have remained stable over nearly half a century, allowing us to predict, in writing and before the events, both the first and second Gulf Wars. This stability suggests that the patterns of capital as power – although subject to historical change from within society – are anything but haphazard.

This type of research has gradually led us to the conclusion that political economy requires a fresh start.

• At about the same time, in 1991, Paul Sweezy, one of the greatest American Marxists, wrote a piece that assessed his co-authored book on Monopoly Capital, published 25 years earlier.

• In that piece, Sweezy admitted that there is something very big missing from both the Marxist and neoclassical theories of capital, and that until that problem was solved, political economy would remain stuck.

• Sweezy, locked into the old framework, admitted quite openly the he had had no idea how to get political economy unstuck.

• But we were younger, and we didn’t carry the old theoretical baggage, and that light-headedness enabled us to apply the Cartesian Ctrl-Alt-Del.

• In our view, the solution to the problem is to view capitalism not as a mode of production and consumption, but as a mode of power.

• And that is what we try to do in our new book.

• Thank you.