Imperialism and Financialism: An Exchange

Joe Francis, Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan[1]

London, Jerusalem and Montreal, September 2009 – January 2010

Below is an exchange of letters between Joe Francis and Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan. The exchange concerns ‘Imperialism and Financialism: A Story of a Nexus’, an article that Bichler and Nitzan posted in September 2009.

September 9, 2009

Letter from Francis to Bichler & Nitzan

Dear Shimshon and Jonathan,

In the following notes I would like to offer a few comments on your recent paper ‘Imperialism and Financialism: A Story of a Nexus’. I’m motivated to do so because over the past few years my research has been influenced by the work of Giovanni Arrighi, as well as your own. It was quite disconcerting, therefore, to see you argue that his theory of ‘hegemonic transitions’ was redundant. Here I would like to point out a few problems with the data that you use to arrive at this conclusion.

You largely base your analysis on two data sources: (1) Obstfeld and Taylor’s data on foreign assets; and (2) Datastream’s aggregates of corporate financial data. I will offer some comments on each.

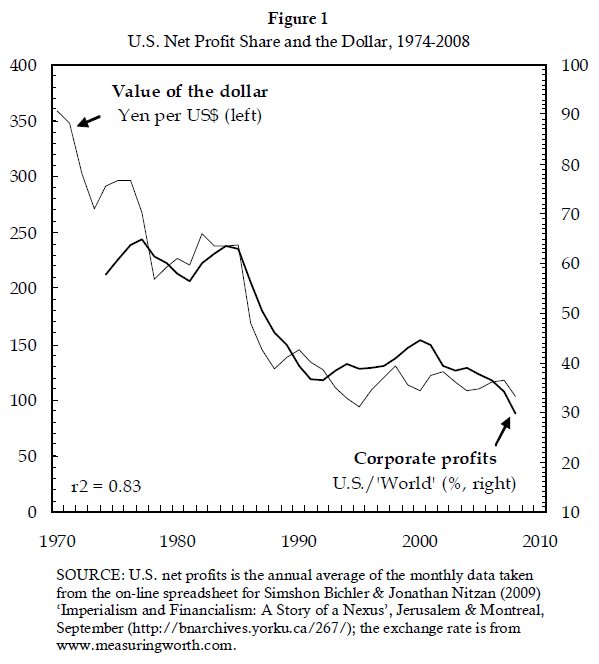

In Figure 1 in your paper, you use Obstfeld and Taylor’s data to demonstrate an unprecedented expansion of the ratio of global gross foreign assets to global GDP. As you note, the construction of these figures required ‘painstaking research to collate and heroic assumptions to calibrate’ (p. 11). Nevertheless, you seem to ignore this caveat in your analysis.

The main problem with the data is representativeness. There are only three countries that are constantly represented during the whole series (Netherlands, United Kingdom, United States). Up to 1960, various other countries are added when data become available. Then in 1980 the sample balloons as data from the IMF’s International Financial Statistics are incorporated. Crucially, it is at exactly this point in Figure 1 that the boom in transnational ownership begins. It seems likely that the boom has been significantly exaggerated by the addition of so many countries in that year.

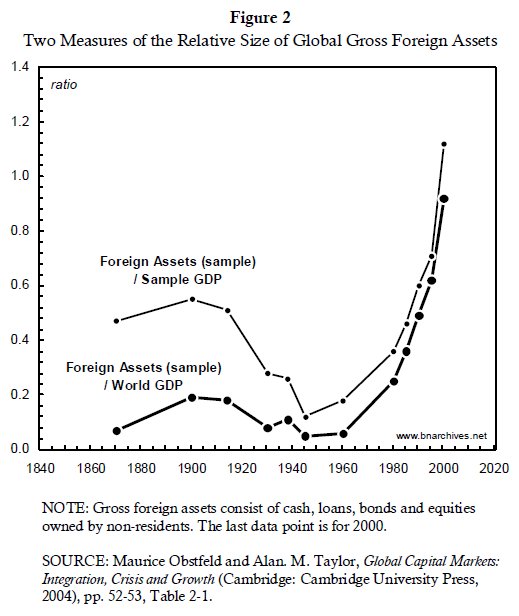

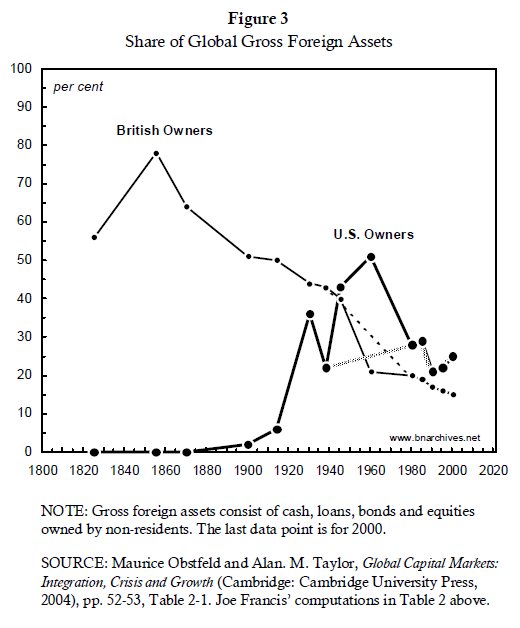

The problem of representativeness applies even more to Figure 2 in your paper. This tracks British and U.S. shares of gross global foreign assets. It appears to show a brief period of U.S. dominance after World War II, which was then ‘undermined the moment capital flow started to pick up’ in 1980 (p. 13). The problem with this image is that the figures for 1945 and 1960 are not comparable with that of 1980. For instance, the data for 1945 include just the three core countries, plus the category of ‘others’ (i.e. non-OECD countries). Thus, continental Europe (apart from the Netherlands) and Japan are excluded. In 1960, other than the addition of Germany, the situation is the same. The magnitude of U.S. dominance during these years is therefore something of a mirage, the result of the absence of other countries from the sample.

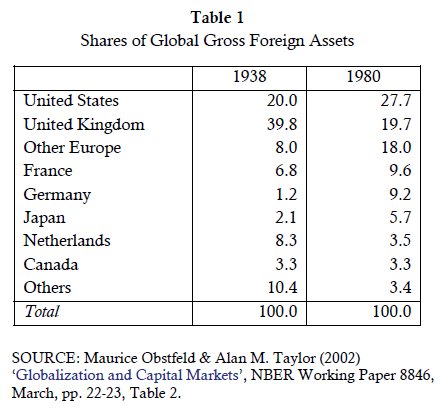

A more accurate comparison would be between 1938 and 1980, years for which there is more complete coverage (see Table 1 below). While there are some interesting observations that can be made about this comparison, a sharp decline in the U.S. share of global foreign assets isn’t one of them.

Table 2, meanwhile, illustrates what Obstfeld and Taylor’s data would look like if the same sample were used for the whole period 1938-1995. Here all the countries which are absent from 1945 have been excluded from every year. Once again, when comparable data are used, there doesn’t appear to have been a great reduction in the U.S. share of global gross foreign assets.

Regarding Datastream, I don’t currently have access to it, so there are limitations on what I can say. Nevertheless, there is one immediate observation that comes from my previous research on Argentina. According to Datastream, Argentina had no stock market prior to 1988. In other words, Datastream contains no data for Argentine stocks prior to that year. Only in the 1990s did it expand to include data on many Argentine corporations. This suggests an initial problem with Figure 3 in your paper. The apparent increase in the Third World’s share of global net profit in the 1990s may just be the result of the expansion of Datastream’s coverage.

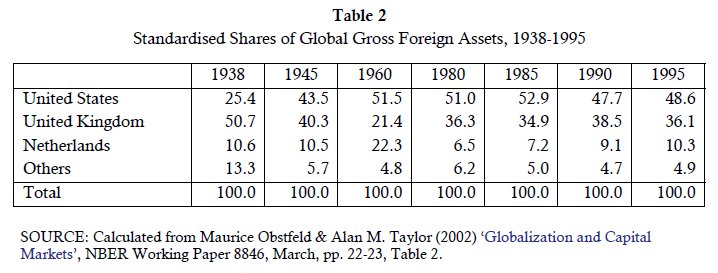

The other thing that struck me about Figure 3 is the sharp decline in the U.S. share of global net profit after 1985. As you put it, ‘During the second half of the 1980s, the net profit share of U.S.-listed firms plummeted, falling to 36% [from roughly 60%] in less than a decade’ (p. 15). This fall coincides with the devaluation of the U.S. dollar after the ‘Plaza Accord’ of September 1985. Indeed, Figure 1 below suggests that the decline in U.S. power (as measured by its share of global net profit) was largely brought about by this devaluation. That, at least, would be the implication of Figure 1 (assuming that net profit share is an accurate measure of global power).

The correlation between the decline of the U.S. profit share and the exchange rate raises questions that could have significant theoretical implications. One possibility is that the devaluation of the dollar actually increased the power of big business within U.S. society. The external assets and income flows of the larger, more transnationalised corporations would have increased in value relative to those of smaller, more domestically-based companies, as well as to the wages of labour. But this interpretation brings us quite a long way from the view that financialisation has damaged U.S. capital. Indeed, to paraphrase you (p. 17), it is precisely when we cease to take the ‘nationality of capital’ at face value that it becomes possible to see that ‘financialisation’ has worked for the hegemonic power, or at least its dominant capital.

Finally, there is little that I can currently say about the data in Figure 4 in your paper. Next month, when I have access to Datastream again, I will look at these figures, and try to identify which were the leading centres of ‘financialism’.

For now, suffice to say that the trend shown in Figure 4 may not be as problematic as you claim. The image of the United States being ‘dragged’ into financialisation by the rest of the world is quite compatible with Arrighi’s theory of hegemonic transitions. Arrighi does not claim that the ‘financial expansion itself is led by the hegemonic state in an attempt to arrest its own decline’ (p. 10). Rather, financial expansion is presented as something that the U.S. government was inextricably drawn into, through processes beyond its control:

The formation of the Eurodollar or Eurocurrency market was the unintended outcome of the expansion of the US regime of accumulation. An embryonic ‘dollar deposit-market’ first came into existence in the 1950s as a direct result of the Cold War. . . .

Communist dollar balances were very small and Eurocurrency markets would never have become a dominant factor in world finance were it not for the massive migration of US corporate capital to Europe in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Large US multinationals were among the most important depositors in the New York money market. It was only natural, therefore, that the largest among New York’s banks would promptly enter the Eurodollar market, not just to take advantage of the lower costs and greater freedom of action afforded by offshore banking, but also to avoid major losses in deposits. And so they did, controlling a 50 per cent share of the Eurodollar business by 1961.

… [T]his amassing of liquid funds in Eurodollar markets became truly explosive only from 1968 onwards. The question then arises of what provoked this sudden explosion, which quickly became the single most important factor in the destabilization and eventual destruction of the post-war world monetary order. Since at this time US transnational corporations probably were the most important depositors in Eurodollar markets, the explosion must be traced to some change in the conditions of their self-expansion.[2]

Arrighi’s answer is that the ‘financial expansion’ was a response to a profitability crisis that afflicted U.S. big business in the late 1960s and ‘70s. Rising wages and increased competition squeezed profits, leading transnational corporations to move away from ‘productive activities’ towards more speculative investments.

This account of financialisation is fully compatible with Figure 4 in your paper. The much higher share of listed FIRE corporations in net profit in the rest of the world could be a result of U.S. corporations’ earlier investments in these countries. Once again, much depends on how seriously one takes the ‘nationality’ of Datastream’s aggregates. Further analysis, and particularly disaggregation, of Datastream’s numbers is needed to determine the extent to which U.S. transnational corporations accounted for the profits of the FIRE sector in the rest of the world.

Saving that for the future, here I have tried to question some of the ‘inconvenient facts’ that you present in your paper. I have argued that some of them are not really that ‘inconvenient’ for the theory of hegemonic transitions, while others are not actually ‘facts’ at all. That said, I do agree wholeheartedly that radical scholars need to pay much more attention to the empirical evidence.

I hope you do not mind me offering these comments. If you like, I can send you my analysis of Datastream’s numbers once I have had a chance to look at them.

Regards,

Joe

September 13, 2009

Letter from Bichler & Nitzan to Francis

Joe:

Thank you for the very interesting and pointed critique. It was a real pleasure to read, and Shimshon and I discussed it at some length. Below I summarize some of our thoughts.

1. Preliminary considerations

These considerations may be obvious, but they are useful to reiterate nonetheless.

The article ‘Imperialism and Financialism: A Story of a Nexus’ does not constitute our own analysis of capitalist development. Instead, it offers a critical review of the conventional creed and how it evolved over time. In focusing on the nexus of imperialism and financialism, our purpose is not to pick and choose. We are not trying to decide which version is correct in some universal sense, and not even which version was correct for its time. Obviously, such discussion requires a much deeper engagement. Rather, our aim is to highlight the historical development of the nexus, and in particular the loose manner in which it has been altered – to the point of meaning everything and nothing.

In line with this broader purpose, our discussion of hegemonic transition isn’t meant to decide whether the U.S. is in decline or not; our goal is simply to show that the theory of hegemonic transition is yet another version of the nexus, and that this version too is now running into trouble.

Note that because we do not offer our own account, our critique sticks to the categories and units of the theories themselves. As you surely know, we ourselves are very critical of these units and categories. For us, the concepts of labour value, surplus value and unequal exchange; the dualities of finance-real and productive-unproductive; and the aggregate-statist bent of the entire framework are all questionable entities, to put it politely. Our comments below should be read with these qualifications in mind.

2. Figure 1 in ‘Imperialism and Financialism’

You are correct that the sample of countries is growing over time. This fact is discussed by Obstfeld and Taylor and is noted in footnote 17 of our article. And you are also correct that if we keep the sample of countries unchanged, the results are different from those presented in our article. But in our view, freezing the sample may not be the correct solution here.

The problem is simple: if the newly added countries were relatively insignificant in terms of inward and outward foreign capital stocks before they were included in the sample (which may be one reason why there were no data on them in the first place), and if the growth rate of their foreign capital stocks accelerated after they were added to the sample, then their exclusion would conceal the very process of change you wish to capture.

Obsfeld and Talyor take a different route to address this issue. Instead of freezing the sample of countries, they recalibrate global GDP as shown in Figure 2 here. The thick line is the ratio we show in Figure 1 of ‘Imperialism and Financialism’. This series compares the foreign capital stock of the changing sample of countries to global GDP. The thin line shows Obstfeld and Taylor’s recalibrated series. For each year, the line measures the foreign capital stock relative to the GDP of only those countries included in the sample.

Each measure has its own pros and cons. The first reflects the growth of the global GDP benchmark; the second limits the benchmark to the fluctuating sample. Regardless of this difference, however, the overall movement of the two series is the same – although the magnitudes are not, particularly in the earlier period when the sample of countries was smaller (see footnote 17 in ‘Imperialism and Financialism’). But according to both series, it seems that during the 1980s (early 1980s in the first case, late 1980s in the second) the ownership of capital became more transnational than ever before. (Note that the figure doesn’t include the 2003 update; this update shows a 20% jump in the ratio of the thick line and probably a similar increase in the thin one.)

3. Figure 2 in ‘Imperialism and Financialism’

Your claims regarding this figure are factually correct: freezing the sample changes the country shares. Figure 3 below shows the consequences of such a freeze. The black series are those presented in ‘Imperialism and Financialism’; the gray series (for the United States) and the dashed series (for Britain) are computed with the constant sample of countries listed in your Table 2.

The new data show a somewhat different picture, but the change doesn’t seem to alter the conclusions radically. Between 1938 and 1980, the U.K. is still in free fall. The U.S., as you suggest, seems to move sideways rather than up and down, but that sideways movement may simply be the result of missing data for the years between 1938 and 1980. Given the post-war outward investment boom of U.S.-based TNCs, it isn’t far fetched to think that during that period their world asset share reached 30-40%.

One way or the other, it seems reasonable to conclude (1) that U.S. owners have never reached the dominance of their U.K. counterparts; and (2) that, after the 1980s, the capital flow boom hasn’t boosted their position (and may even have undermined it). Of course, these conclusions remain consistent with hegemonic decline.

4. Figure 3 in ‘Imperialism and Financialism’

Your suggestion that the declining profit share of the U.S. was disproportionately affected by the devaluating dollar is very interesting and rather plausible. But why would this effect invalidate our claims? Doesn’t hegemonic transition theory consider the long-term decline of the dollar as a key manifestation of the decline of U.S. hegemony? In principle, devaluation could have helped U.S.-based firms to increase their foreign market share and, by extension, their share of global profit. But that increase hasn’t happened – another indication for the relative weakness of these firms.

You also argue that devaluation may have boosted the differential power of dominant capital relative to their smaller U.S. counterparts because the former’s profits benefitted disproportionately from appreciating foreign earnings. This claim may or may not be correct. But how does it affect the broad question of hegemonic transition and the issue of whether the U.S. has risen or declined in the aggregate?

Finally, you mention that the Datrastreem universe is changing, and that some markets were included only very late – for instance, Argentina only in 1988. Again, this claim is correct and worth making; it is equivalent, on a larger scale, to the process of private firms going public for the first time and in so doing inflating the sample of listed firms. But then, why were these markets excluded until the 1980s? In most cases, the answer is simple: they had an insignificant market capitalization and therefore little data infrastructure (in most cases they were also relatively or completely closed to foreigners). Had Datastream included these markets in its universe from the early 1970s, the profit share of firms listed in our ‘Rest of the World’ category would have been higher by definition – but probably by no more than a notch.

5. Arrighi

The underlying claim of hegemonic transition theory (Arrighi’s as well as others) is that eventually the hegemon gets eviscerated for various reasons, and that this evisceration always drives the hegemon, consciously or unconsciously, toward the temporary ‘solution’ of financialization. The quotation you cite from Arrighi seems rather consistent with this view: accumulation regime reaching its limits → profitability crisis → financialization → migration of U.S. capital → U.S. TNCs being the largest depositors, etc. Whether or not this process was explicitly articulated by government officials is rather irrelevant (note that in ‘Imperialism and Financialism’ we use the vague concept of the hegemonic state, not of its government).

Finally, you claim that the higher FIRE share of corporate profit outside the United Sates may have been due to earlier U.S. foreign investment there. The logic of this claim is unclear: why would such U.S. investment make the share of foreign FIRE firms greater than the share of U.S. FIRE firms?

6. Conclusion

This exchange is stimulating and fruitful. We greatly appreciate it.

Jonathan and Shimshon

September 15, 2009

Letter from Francis to Bichler & Nitzan

Dear Jonathan and Shimshon,

Thanks for your response. You ask various questions that I will try to answer here.

Unfortunately, I still haven’t been able to access Datastream, so I can’t elaborate much on that subject. Partly for that reason, here I will focus less on the numbers and more on the ideas contained in your paper ‘Imperialism and Financialism’.

1. A disappearing nexus

In the paper, you argue that in conventional Marxist theory there is a nexus between ‘imperialism’ and ‘financialism’. This nexus has not, however, been constant, and has evolved over time. Indeed, you argue that the nexus has been altered so much that it now appears to explain everything and nothing.

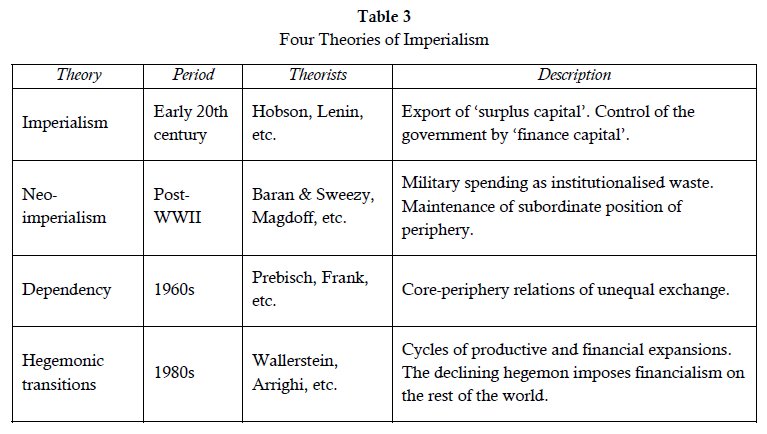

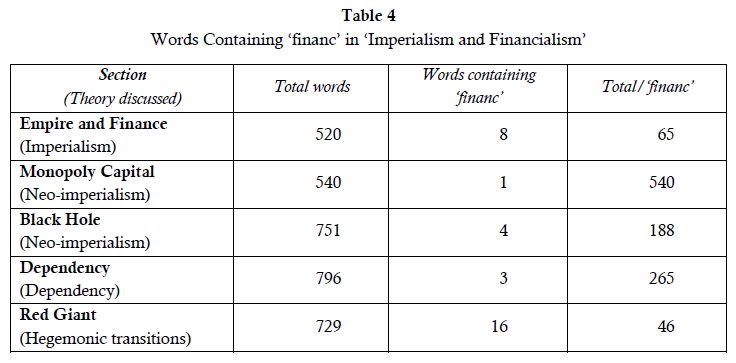

You claim to trace this nexus across four theories of imperialism. These are summarised in Table 3.

Immediately, it is possible to see a problem with your narrative: in two out of four theories there is no nexus between imperialism and financialism. Specifically, in the theories of neoimperialism and dependency, financialism plays little part. Here I will illustrate this by describing each theory in turn.

According to the original theory of imperialism, there clearly was a nexus. As John Hobson put it, ‘Aggressive Imperialism, which costs the tax-payer so dear, which is of so little value to the manufacturer and trader, which is fraught with such grave incalculable peril to the citizen, is a source of great gain to the investor who cannot find at home the profitable use he seeks for his capital, and insists that his Government should help him to profitable and secure investments abroad’.[3] British imperialism was driven by a small financial oligarchy that was unable to find profitable investments in its own country. It therefore took to lending to foreign governments, using the military might of its own government to ensure that the debts were repaid. Here, then, was a clear nexus between imperialism and financialism.

However, that nexus is much less evident in the theories of neo-imperialism and dependency. In both cases, financialism is given little attention. For instance, Harry Magdoff, provides the following summary of imperialism:

(1) The most obvious first requirement to assure safety and control in a world of tough antagonists is to gain control over as much of the sources of raw materials as possible – wherever these raw materials may be, including potential new sources. . . .

(2) The pattern of most successful manufacturing businesses includes conquest of foreign markets. This is so even where there is as large an internal market as in the United States. . . .

(3) Foreign investment is an especially effective method for the development and protection of foreign markets. . . .

(4) The drive for foreign investment opportunities and control over foreign markets brings the level of political activity on economic matters to a new and intense level . . . Other political means – threats, wars, colonial occupation – are valuable assistants in clearing the way to exercise sufficient political influence in a foreign country to obtain privileged trade positions, to get ownership of mineral rights, to remove obstacles to foreign trade and investment, to open the doors to foreign banks and other financial institutions which facilitate economic entry and occupation.[4]

Here, then, the emphasis is on securing supplies of raw materials and capturing foreign markets. Finance is given a facilitating role, but it is not seen as driving the process.

In theories of both neo-imperialism and dependency, imperialism is portrayed as a result of the exigencies of production (securing raw materials) and trade (capturing foreign markets). ‘Finance’, ‘financialisation’, et cetera are virtually absent.

Indeed, an indication of this can be found in your own description of these theories. Table 4 illustrates this by counting the number of words containing ‘financ’ in the five sections of your paper that describe the four theories. As can be seen, words containing ‘financ’ appear quite frequently in your outline of the original theories of imperialism; but they become much less common in your discussion of neo-imperialism and dependency theories. This is because financialism hardly features in those theories; hence the nexus disappears when you discuss them. It only reappears when you move on to the theory of hegemonic transitions.

This disappearance of the nexus from Marxist theories of imperialism has a simple explanation. During the 1940s-60s, ‘finance’, as commonly defined, played a less important role in capitalism. It was the era of ‘embedded liberalism’ and ‘financial repression’. It was only in the 1970s-80s that finance became liberated, as unembedded ‘neoliberalism’ entered the picture.

In other words, for Marxist writers of the 1940s-60s there appeared no need to incorporate an analysis of financialism into their theories of imperialism. Indeed, the nexus between the two, which had been such a prominent feature of the earlier theories of imperialism, now seemed redundant – an obstacle to understanding the international relations of the day.

By contrast, for those writing during the 1970s-80s, it became necessary to revisit the nexus. Giovanni Arrighi’s theory of hegemonic transitions was one of the most original attempts to do so.

Building on the original work of Fernand Braudel and other historians, Arrighi provided a grand overview of capitalist development since the 16th century. He argued that there had been ‘three hegemonies of historical capitalism’, first the Dutch, then the British, and most recently the U.S. Each began with a ‘material expansion’ and ended with a ‘financial expansion’:

These are cycles of the world capitalist system—a system which has increased in scale and scope over the centuries but has encompassed from its earliest beginnings a large number and variety of governmental and business agencies. Material expansions occur because of the emergence of a particular bloc of governmental and business agencies which are capable of leading the system towards wider or deeper divisions of labour. These divisions of labour, in turn, increase returns to capital invested in trade and production. Under these conditions, profits tend to be ploughed back into further expansion of trade and production more or less routinely, and knowingly or unknowingly, the system’s main centres cooperate in sustaining one another’s expansion. Over time, however, the investment of an ever-growing mass of profits in the further expansion of trade and production inevitably leads to the accumulation of capital over and above what can be reinvested in the purchase and sale of commodities without drastically reducing profit margins. Decreasing returns set in; competitive pressures on the system’s governmental and business agencies intensify; and the stage is set for the change of phase from material to financial expansion.[5]

Arrighi’s narrative provides a bridge between the original theories of imperialism and the more recent theories of neo-imperialism and dependency. Raw materials and foreign markets are the priority during the material expansion, while capitalists look abroad for financial instruments to invest in during the financial expansion. In this way, Arrighi reconciled Magdoff with Hobson.

It would seem logical to extend Arrighi’s analysis by arguing that there have been two types of imperialism, corresponding to the cycle’s two phases. ‘Material expansion’ requires ‘material imperialism’, focused on foreign markets and raw materials, while ‘financial expansion’ requires ‘financial imperialism’, characterised by Third World debt crises and booms in ‘emerging market’ portfolios. It is only in the latter that the nexus between imperialism and financialism exists.

2. False dichotomies?

A possible riposte to this argument would be that material/financial is a false dichotomy. From a business perspective, it doesn’t matter whether you invest in a factory or speculate on exchange rates. What matters is profit, and that is inherently financial.

While I have some sympathy for this argument, it does seem that from a non-business perspective, there has been a huge difference between the phases of material and financial expansion. This can be clearly seen in the case of Argentina, the subject of my own research.

To begin with, I have to note that the case of Argentina seems to contradict your claim that ‘the flow of capital is financial, and only financial. . . . There is no flow of material or immaterial resources, productive or otherwise. The only things that move are ownership titles’ (p. 11, emphasis in original). This statement seems odd because in Argentina in the 1960s direct investment mainly took the form of importing used machinery from the First World and installing it in factories in Argentina. Thus, during the phase of material expansion identified by Arrighi, foreign investment literally took the form of moving machinery from one country to another.[6]

By contrast, from the military dictatorship of 1976-1983 onwards, foreign investors, and investors in general, increasingly engaged in speculative activities. As you suggest, foreign investors were now buying existing assets, transferring titles of ownership, generally with the intention of selling them later for a profit. In Arrighi’s terms, this was the phase of ‘financial expansion’, characterised by IMF-imposed ‘financial imperialism’.

For big business the shift from material to financial expansion came quite naturally. As a prominent Argentine historian put it, the country’s largest industrial corporations simply became ‘financial agents that had a factory’.[7] Yet for the rest of society, the change was catastrophic. There was deindustrialisation, and the country entered a prolonged period of decline in its relative wealth. From 1950 to 1975 the country’s GDP per capita had remained stable at 45-50% of U.S. GDP per capita, but it then shrank to just 30% by 1990.

Arrighi’s theory of hegemonic transitions provides a useful framework for understanding these transformations. During the phase of material expansion, Argentina was able to maintain its level of relative wealth, but it then went into a sharp decline during the phase of financial expansion. I suspect that the story is similar for numerous Third World countries.

The dichotomy of material/financial does, therefore, have some relevance for helping us understand the course of capitalist development. It may be false from a purely business perspective, yet it appears highly relevant from a broader, more social point of view.

3. Global gross foreign assets

Regarding Obstfeld and Taylor’s data, firstly I should apologise for being so pedantic about the numbers, especially since I missed footnote 17, in which you had already noted some of my misgivings. I think you are quite right that the trend in Figure 1 in ‘Imperialism and Financialism’ is correct, even if it has been exaggerated slightly by the lack of data for the earlier years.

That said, I do still have a minor problem with Figure 2 in ‘Imperialism and Financialism’. Britain’s share of global foreign assets in 1855 appears hugely exaggerated due to the omission of France, its main competitor. If the data for France were available, I suspect that Britain would be around 60% of the total, rather than the 78% given by Obstfeld and Taylor. This is, however, further pedanticism on my part.

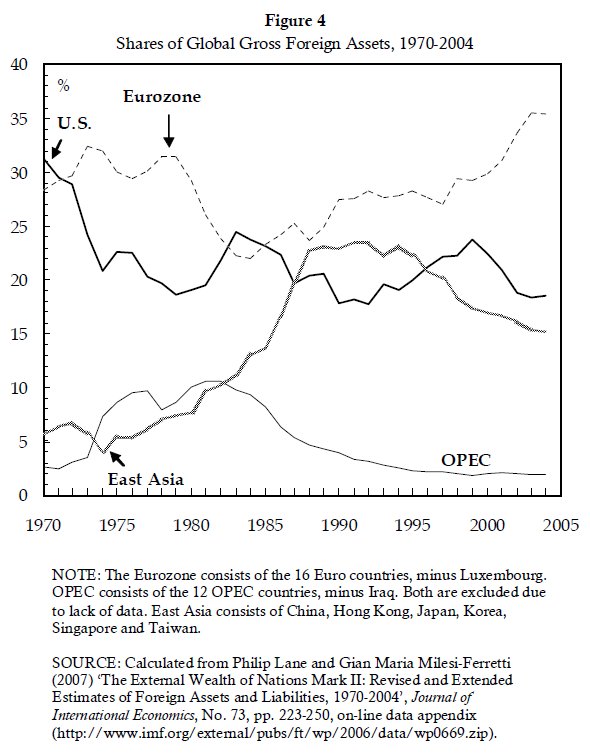

Nitpicking aside, Figure 4 below presents a more nuanced view of the distribution of global gross foreign assets since 1970. It is based on the IMF data that you use to extend Obstfeld and Taylor’s series. Here global gross foreign assets are calculated as the total of all the available data. Again this will have distorted the numbers in the early years due to the absence of some countries. Nevertheless, the distortion is probably insignificant.

Several things can be noted about Figure 4 here:

(1) The decline of the United States is still evident. However, the worst of this decline appears to have occurred in the first half of the 1970s, i.e., before the financial expansion began in earnest. Indeed, the turn towards financialism in the second half of the 1970s/early 1980s appears to have stopped the decline in the U.S. share. Moreover, if we assume that the United States had previously achieved a 40% share around 1960, it must also have experienced a significant decline in the 1960s, during the phase of material expansion.

(2) For most of the 1970s, U.S. decline was paralleled by the rise of the OPEC countries. However, the negative correlation between the two series ends around 1980. The OPEC share then peaks and declines.

(3) The new ‘contender’ then becomes East Asia, which sees its share increase from 4% in 1974 to 23% in 1994. This process received a boost from the revaluation of the yen in 1985, which allowed Japan to buy up considerable foreign assets. It came to a halt, however, as Japanese capitalism entered its lost decade of the 1990s.

(4) Europe then replaced East Asia as the most dynamic region. This was the result of unification, and raises the important question of whether German investment in France should really be considered foreign investment, or whether both now share a sufficiently European identity to be considered part of the same state. . . .

In conclusion, Figure 4 throws some doubt on your argument that financialism decreased U.S. power (as measured by its share of global gross foreign assets). It would be interesting to update Figure 4 to include the last few years and the effects of the war in Iraq and the banking crisis. I will try to do so in the future.

4. Devaluation and U.S. power

In your reply, you asked me several questions related to the effects of dollar devaluation on the power of U.S. business. I presented a graph that appeared to show that devaluation was the primary cause of the decline of the global profit share of U.S.-listed corporations. You then asked how this related to the theory of hegemonic transitions. ‘Doesn’t hegemonic transition theory consider the long-term decline of the dollar as a key manifestation of the decline of U.S. hegemony?’

By demonstrating the relation between the exchange rate and the U.S. profit share, I wanted to suggest two things.

Firstly, that any new (or just improved) theories of imperialism and international relations should pay substantial attention to exchange rates. Up to now, I would say that all Marxist theories of imperialism have paid insufficient attention to this issue, principally because they are too concerned with the ‘real’ sphere of production.

Secondly, I tried to raise the question of what exactly the U.S. bourgeoisie wants. On the one hand, dollar devaluation appears to have harmed U.S. power vis-à-vis the rest of the world. However, I also argued that devaluation must have increased the power of U.S. big business over the rest of U.S. society. Large companies are generally much more transnationalised than their smaller counterparts, so more of their income comes in foreign currencies. This means that devaluation must have increased their dollar incomes simply through an adjustment in the exchange rate. By contrast, smaller companies and labour would not have seen such an increase. Therefore, devaluation could have increased the power of U.S. big business over domestic society, while simultaneously weakening it vis-à-vis foreign competitors.

This raises the question of what the priorities of the U.S. bourgeoisie are: power within the United States or world power? Given my European stereotypes about the insularity of North Americans, I would suggest the former. . . .

But what does all this mean for theories of hegemonic transitions? Again, I’m not sure. An answer will have to wait until my ideas are less half-baked.

5. The nationality of capital

One of the problems that prevents me from coming to any firm conclusions on the issue of devaluation is that I’m still unsure about how much devaluation actually decreased the net profit share of U.S. corporations. Note that I refer here to ‘U.S. corporations’ rather than ‘U.S.-listed corporations’. The ‘nationality of capital’ is of prime importance.

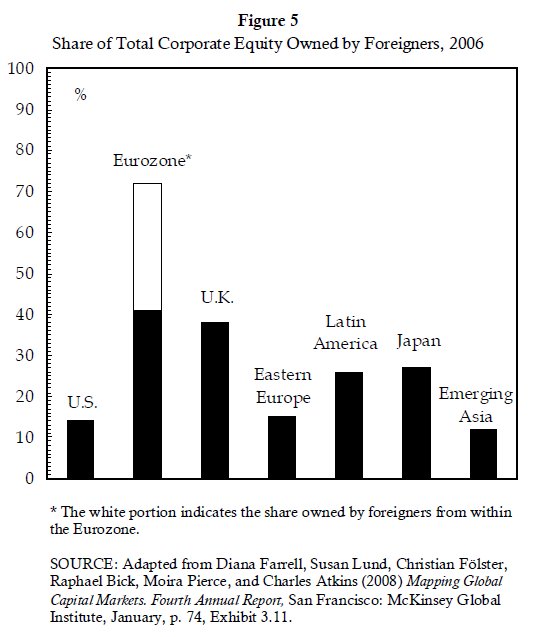

The McKinsey Global Institute report that you cite in ‘Imperialism and Financialism’ contains a very interesting graph that I have adapted in Figure 5 below. According to these data, the U.S. domestic corporate universe was one of the least transnationalised in the world. Only 14% of the equity of U.S.-listed corporations was held by foreigners in 2006. By contrast, in the Eurozone 41% of equity was held by foreigners, increasing to 72% if you include foreigners from within the zone. Indeed, even Japan, a country that is notoriously difficult to penetrate for foreign investors, had a much higher level of foreign ownership than the United States.

This raises various questions, three of which I will mention here:

(1) Regarding devaluation. The profit share of U.S.-listed corporations may have decreased with dollar devaluation, but was that compensated for by an increased profit share of U.S. corporations operating abroad? Figure 5 makes this question particularly urgent because of the extremely high level of foreign ownership in the European Union. Collectively, E.U.-listed companies increased their share of global net profit from 16% in 1984 to 30% in 2005.[8] If a substantial chunk of this share was claimed by U.S. corporations listed in Europe, it would have at least partially compensated for the fall in the profit share of U.S. listed corporations.

(2) Regarding the FIRE sector. Your main argument against the theory of hegemonic transitions is that the United States was not ‘the engine of ‘financialization’’, and that it was actually ‘‘dragged’ into the process by the rest of the world’ (p. 20). You illustrate this argument with Figure 4 in your paper, which shows that the FIRE sector has consistently accounted for a higher share of profits in the rest of the world than in the United States. This argument becomes questionable when you consider that so much of the rest of the world is foreign-owned. To what extent are the rest of the world’s FIRE profits shown in Figure 4 in your paper accounted for by U.S. corporations operating abroad? Did the arrival of these U.S. corporations in the 1960s lead to the relatively high level of FIRE profits indicated in Figure 4? Was financialisation actually driven by U.S. corporations operating outside of the United States?

(3) Regarding theories of imperialism. What does it mean for the global distribution of power that so much of corporate equity in the rest of the world is owned by foreigners, while U.S. corporations remain more or less nationally owned?

6. Five assertions

In these notes I have offered further reflections on your paper ‘Imperialism and Financialism’. In doing so, I have made five assertions:

(1) In two out of the four theories that you describe there isn’t a nexus between imperialism and financialism. Financialism hardly enters the picture in theories of neo-imperialism and dependency because they were formulated during a phase of ‘material expansion’. It was only during the more recent phase of ‘financial expansion’ that it became necessary to resurrect the nexus.

(2) We should maintain some dichotomies, particularly material/financial. These dichotomies may not be ‘real’ from a business perspective, but from a social perspective there is a huge difference between the different phases of capitalist development.

(3) U.S. decline was checked by the financial expansion. This assertion is based on the revised figures for the share of global gross foreign assets.

(4) In order to improve our understanding of international relations we need to consider what exactly it is that the U.S. bourgeoisie wants. Is it primarily concerned with power over U.S. society or over foreign competitors? Does the urge to dominate transcend national boundaries?

(5) We need to look at the ‘nationality of capital’, particularly as U.S. corporations appear to have remained relatively national. I believe this issue creates major problems for your argument that financialisation was not driven by the United States.

More generally, I have argued that Arrighi’s theory of hegemonic transitions remains a useful framework for understanding the present conjuncture. No doubt, attempting to combine it with your own theories will give me no end of headaches over the coming years. Finally, I am not particularly convinced by any of my assertions, and I would have to elaborate substantially to turn them into convincing arguments. That said, I have enjoyed putting them out there. I too have found this exchange stimulating and fruitful.

Best,

Joe

September 22, 2009

Letter from Bichler & Nitzan to Francis

Joe:

Thanks for your rejoinder. Below are some of our thoughts on your arguments. It would be good to explore these issues further when we meet at Amherst in early November.

1. Historical embeddedness

In some sense you are bursting into an open door. The theories we cover contain logical and empirical shortcomings, but these shortcomings lie largely outside the scope of our paper (these and other failings of political economy are assessed in our 2009 book, Capital as Power). As noted in our first letter, the article ‘Imperialism and Financialism’ doesn’t argue for or against the different theories it reviews, at least not in any strict sense. Our purpose, rather, is to point out what happens when theorists use the same concepts to describe radically different realities. Every one of the theories we cover is a creature of its time, so to speak; and for a while each one of them made sense and provided a coherent perspective. However, much like their neoclassical counterparts, Marxists have attempted to retain the pristine elegance of their nineteenth century concepts; and as the world continued to change, their concepts, inevitably, started to mismatch reality.

During the early part of the twentieth century, for example, it seems plausible to understand the Standard Oil of New Jersey and the U.S. State Department as organs of imperialism (see for instance the memoirs of Marines Major General Smedley Butler, War is a Racket). By the mid-twentieth century, however, this picture no longer made sense. So instead radicals started to speak of a neo-imperial order, dominated by the U.S. power elite and organized through a system of Monopoly Capital – a framework that was taken more or less as given by dependency writers. But these theories and ideologies, being historically embedded, have now run their course. They can tell us very little about the contemporary reality of Exxon and the U.S. government – or the reality of PetroChina and the Chinese government for that matter.

Similarly, in the nineteenth century, when financial intermediation appeared more or less delineated from factory production, speaking about ‘fractions’ of capital seemed to make sense. But today, when this delineation means little in practice, not to say in principle, theories that contrast ‘financial’ and ‘industrial’ capitalists look like bad caricatures.

Note that we do not advocate discarding the earlier theories. These theories were relevant when they were first articulated, and in that sense they remain a permanent part of our understanding. Moreover, they often continue to make sense at a certain level of analysis (on this issue, see the discussion in our book, Capital as Power, of the politics-economics duality on page 30, and of enfoldment in footnote 1 on page 307).

However, historical embeddedness suggests that we should be careful when trying to fuse theories from different epochs. You argue that hegemonic transition theory ‘bridges’ old- and neo-imperialist theories by linking different phases of ‘production’ and ‘finance’ – and on the face of it this bridging seems tempting. But if the concepts and realities underlying these two approaches are no longer the same – or worse still, if they are contradictory – their fusion could be very misleading.

2. The disappearing nexus

Sleazy trick there with word counting . . . and you are correct that the ‘strength’ of the nexus hasn’t been constant. However, your thematic breakdown of our argument is misleading. As noted above, theories of neo-imperialism and dependency are not really separate from but inextricably bound up with Monopoly Capital. The shift toward neo-imperialism was predicated on Monopoly Capital domesticating surplus absorption (partly through finance), while dependency was enabled by the concentrated power of Monopoly Capital to steer the foreign policies of core states. In this sense, the role of ‘finance’ remains deeply embedded in both of these theories.

3. False dichotomy

You are correct that one can identify and distinguish between periods of growth and stagnation, even if their measurement is problematic, and that the difference between such periods is crucial for the underlying population and for social development more generally. But in our view, this distinction does not imply a parallel duality between ‘material’ and ‘financial’ phases of capital accumulation (the reasons for this latter claim, too long to spell out here, are articulated in our book, Capital as Power).

Regarding your points about foreign investment in Argentina, we believe that your argument is wrong. Capital inflows to Argentina – or to any other country – are always financial, by definition. The fact that these inflows are sometimes followed by the importation of machines (a change in the asset side of the balance sheet from cash to equipment) is irrelevant to the act of foreign investment (a change in the liabilities side, shifting equities from one owner to another) (see footnote 16 in ‘Imperialism and Financialism’). More generally, investors are always forward looking, and in that sense they always speculate. This conclusion holds regardless of whether they buy a bank or a company than owns factories. Finally, for capitalists, the ultimate purpose of purchasing an asset is not to sell it, but to have it appreciate in value relative to other assets; the asset will be sold only if the owner feels that other assets promise a better risk/return combination.

4. The nationality of capital and the ‘goals of U.S. capitalists’

You are correct in pointing out that foreign ownership of U.S. corporations – 14% in 2006 – is lower than foreign ownership in other leading countries. One important reason is that the U.S. corporate asset base remains the largest in the world, even in dollar terms. Note however that the foreign ownership of U.S. assets more generally – including both equity and bonds – isn’t that low: in 2006, it amounted to nearly 20% -- compared to 30% in the U.K. (see the McKinsey publication you cite, Exhibit 3.12). If we think of capital as an undifferentiated ‘income-yielding asset’ (rather than ‘income yielding corporate equity’), it seems that a sizeable chunk of U.S. capital is foreign owned.

But in our opinion, the crucial question here isn’t the precise percentage of foreign investment or even its overall trajectory, but the general disposition toward it. And this disposition seems to have changed fundamentally. In 1987, Kuwait Investment Office (KIO) took advantage of the privatization of British Petroleum to buy 22% of the company’s outstanding shares. At the time, the neoliberal Thatcher government was so horrified by this attack on its national ‘crown jewel’ that it forced KIO to reduce its stake to a more acceptable 9.9 per cent (see our 1989 working paper ‘The Armadollar-Petrodollar Coalition: Demise or New Order?’ pp. 5-6). By contrast, when in 2008 Sheikh Mansoor of Abu Dhabi bought 16% of Barclays Bank – and then sold it less than a year later for a 70% profit – nobody even blinked. The difference? Capital has become totally vendible, within and across borders. There are no crown jewels any more. With the exception of ‘national security’ companies, every asset is now fair game. During the recent crisis, the U.S. authorities literally begged sovereign wealth funds to buy U.S. assets.

Finally, we don’t know how to answer your question, ‘what is it that the U.S. bourgeoisie wants?’ But given the argument in the preceding paragraph, we don’t feel that this is the right question to ask. For capitalists, more power means beating the average; but capitalists don’t have the luxury to pick which average to beat. They are compelled to try to beat the most general benchmark available; and nowadays, when the entire world is open to investment, the most general benchmark is global. Local is less and less of an option.

Best,

Jonathan and

Shimshon

December 5, 2009

Letter from Francis to Bichler & Nitzan

Dear Jonathan and Shimshon,

Thanks once more for your reply. And apologies for the delay. Finally, I had the chance to look at the Datastream numbers, which I will comment upon in a moment.

First, though, I would like to point out an issue that possibly separates us. I am training to be an historian, currently looking at Argentina in the 20th century. I am principally concerned with understanding the past, whereas I think your principal concern is to understand the present and, if possible, the future. This means that some theories will still seem relevant to me, whereas they will appear hopelessly outdated to you. Perhaps being a historian necessarily involves bursting in through a lot of open doors.

For instance, when I ask ‘what is it that the U.S. bourgeoisie wants?’, I am thinking about the objectives of U.S. transnationals investing in Argentina in the 1960s, when the entire world wasn’t open to investment. What criteria for success did they use during this period? How did it differ from the criteria used by Argentine investors? What was their objective? I don’t think I can answer these questions by appealing to a ‘global benchmark’, given that such a thing didn’t exist in the 1960s, even if it does nowadays. Maybe dependency theory and the monopoly capital school will help me understand what was going on when these theories were created.

In what follows I would like to make a few more critical comments about your paper ‘Imperialism and Financialism: A Story of a Nexus’.

1. Financialism and imperialism in Argentina

Firstly, apologies for wordcounting you. It was a sleazy trick. Nevertheless, I think it did demonstrate that if we stick to the standard definitions of ‘finance’ and ‘capital’, there wasn’t a nexus between financialism and imperialism in the theories of neo-imperialism and dependency.

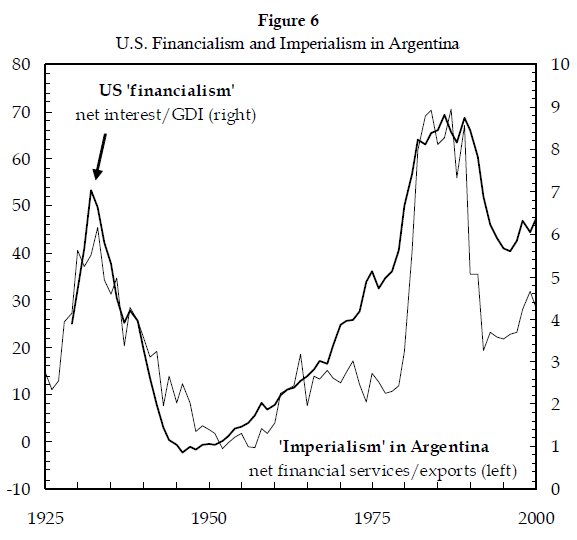

Bearing that in mind, I’d like to offer a little illustration of why the nexus between financialism and imperialism still seems relevant for developing countries. Figure 6 below presents a proxy for the degree of financialism in the core of the global political economy (net interest/gross domestic income in the United States) with another for the degree of imperialism in Argentina (net financial service transfers/exports, from the balance of payments). As can be seen, during the twentieth century high degrees of financialism in the core were associated with more of Argentina’s foreign exchange earnings being siphoned off abroad. A nexus between financialism and imperialism therefore seems like quite a relevant concept. Moreover, Arrighi’s dichotomy of ‘productive’ and ‘financial’ expansion also seems quite relevant, given that the 1940s-70s were a relative ‘golden age’ for Latin America, only ending with the rise of financialism in the 1970s and ‘80s.[9]

2. The United States and financialism

I had a chance to look at the Datastream numbers on global profit shares. Unfortunately, analysing the data didn’t produce any great new revelations. I have made the dataset available on-line at http://www.joefrancis.info/databases/worldpowerdata.xls in case you or anyone else can spot anything that I missed.

While looking at the data, three things came to mind:

(1) I had an idea as to why FIRE sector profits are a smaller percentage of total profits in the United States. It could be because, in historical terms, FIRE sector companies have tended to be listed before other sectors. If this were the case, the lower share of the FIRE sector in total corporate profits would be because the process of capitalisation started earlier there.

(2) Consequently, it would be unfair to compare the absolute level of the FIRE sector’s profits in the United States with that in the rest of the world, so it is impossible to conclude that the United States was ‘catching up’ during that period.

(3) That said, the rapid growth of the FIRE sector’s share of profits in the United States does remain very interesting. Such high rates of growth – much higher than in the rest of the world – suggest that the U.S. FIRE sector was more dynamic than in other countries, possibly driving the processes of financialism across the world. This would, moreover, be more in line with the common sense perception of Wall Street driving ‘financial globalisation’ since the 1980s.

3. Profit shares and world power

The other thing I would like to question is your use of global profit shares to measure world power: Is this really sufficient? There are facets to world power other than profits and ownership. Was China powerful before it had a stock market? Of course: It had a billion people and a nuclear bomb. Therefore, although capitalist power may be captured by this measure, we do not yet live in a ‘purely capitalist’ world, so other facets of power need to be considered.

Moreover, were you to take this as the major determinant of world power, it would mean taking exchange rate policy as the key battleground of global power struggles, since, as I suggested before, the U.S. global profit share appears to have been largely determined by the exchange rate of the dollar. Looking at the Datastream numbers has partially confirmed this claim. Using monthly data smoothed as 12-month moving averages, there is still a close correlation between the U.S. share of global profits and the exchange rate vis-à-vis the Japanese yen (r2 = .85), although it is less clear vis-à-vis the German mark (r2 = .72). I think to test this claim properly, one would need to calculate the U.S. dollar exchange rate vis-à-vis a sample of major currencies weighted according to their share of global profits. For me this is too much work, given that I have further reservations about this whole debate.

4. Three bald men?

Up to now, it is quite possible that we have been like three bald men arguing over a comb. I don’t think any of us is particularly interested in quantitatively measuring the extent of ‘US power’; yet it is precisely over such measurements that we have been arguing. None of us, I believe, is particularly concerned with the ‘nationality of capital’.

In Argentina, for much of the post-war era there was a great concern to create a ‘national bourgeoisie’. The idea was that foreign capital was ‘imperialist’ and only concerned with ‘exploiting’ Argentina, whereas national capital would pursue ‘development’. And so, beginning in the early 1970s, numerous measures were adopted to promote the formation of large Argentine-owned companies: public funds were invested in them, public companies were obliged to buy from them, public credit was redirected towards them. The irony of this story is that the Argentine conglomerates that benefited from this government largesse had little interest in ‘development’. After various financial reforms in the late 1970s, they turned their hand toward currency speculation while overseeing the country’s deindustrialisation. Later these same conglomerates would participate in the privatisation of the public sector, then sell their Argentine assets to foreign investors and send their capital abroad.

This story suggests that over the past 30 years or so, the nationality of capital has become decreasingly relevant for understanding Argentina. Perhaps a more relevant conceptual framework would be something closer to Hardt and Negri’s Empire (Harvard, 2000), although without so much overblown verbiage and some (!) empirical content. Moreover, such an approach is much more in line with Marx and Engels’ original view of capitalism as a totalising order, using prices to batter down Chinese walls.

In conclusion, I have criticised various aspects of your paper ‘Financialism and Imperialism’. I think that some of my criticisms were sound, while others were less so. The U.S. share of global foreign assets did stabilise with the take-off of financialism in the mid-1970s; however, given my reservations about the concept of the ‘nationality of capital’, I’m not sure this measure is particularly meaningful. Ditto the evolution of global profit shares.

On the other hand, I believe that Arrighi’s distinction between ‘productive’ and ‘financial’ expansions remains a useful one. Moreover, I have demonstrated that during the twentieth century, at least in Argentina, financial expansions were associated with higher degrees of ‘imperialism’. Therefore, the nexus still stands.

Finally, I would like to thank you for this correspondence, especially for your willingness to respond to my criticisms – openness to debate is not a virtue shared by all academics. This is a shame because for me this has been a highly enjoyable and productive exchange.

Warm regards,

Joe

January 15, 2010

Letter from Bichler & Nitzan to Francis

Dear Joe:

Thank you for your letter of December 5, 2009. It seems that we have sufficiently clarified our respective positions, and that the time has come to wrap up the exchange, at least for the time being. Before signing off, though, we would like to make one last point.

The key purpose of our article was to illustrate how the terms ‘imperialism’ and ‘financialism’ – and the nexus between them – have been altered and reinterpreted to the point of meaning everything and nothing. The consequence of this dilution is illustrated in the way you explain your Figure 6 on ‘U.S. financialism and imperialism in Argentina’.

Your figure shows a tight historical correlation between the U.S. share of net interest in GDP, on the one hand, and the Argentinean ratio of net financial services to exports, on the other. You interpret the first series as a proxy for U.S. ‘financialism’ and the second series as a proxy for ‘imperialism’, and you argue that their correlation shows that the nexus between them is still relevant.

We find this to be a very neat chart. However, elegance notwithstanding, your interpretation of this chart and the conclusions you draw from it seem unwarranted.

1. Terminology

Begin with the term ‘financialism’. This term is rooted in the classical debate on the source of productivity, a controversy that began with the French Physiocrats, if not earlier, and that continues to haunt economists till this very day. Situated in this larger debate, Marxists tend to identify economic activity as productive if it generates surplus value. Industry, they say, generates such surplus value and therefore is productive; by contrast, commerce and finance do not generate surplus value, which makes them unproductive. The concept of financialism draws on this distinction. It denotes a shift of emphasis from productive industrial activity to unproductive financial activity – a process that is dominated by financiers, directed by financial organizations and governed by the logic of financial intermediation.

Now, as you surely know, we reject the basic terms of this debate and, by extension, the very concept of financialism. Regardless of our own view, though, your data in Figure 6 do not seem to say much about financialism. These data do not show the growing importance of financiers; they do not show the greater role of financial intermediation; and they do not show the increasing subjugation of society to the principles of financial calculations. All they do is plot the share of net interest in GDP.

To be sure, the net interest share of GDP is an important ratio. But, taken on its own, it has little to do with financialism. In the national accounts, the magnitude ‘net interest’ denotes the interest payments that private enterprises make to their creditors less the interest payments that private enterprises receive from their debtors. This net interest, like profit, is a legal classification of capitalist income. In this classification, net interest is the return on debt, whereas profit is a return on equity. And that’s basically it.

There is no correspondence between interest and profit on the one hand and the type of production on the other. All corporations – whether they are an Exxon (typically classified as ‘industrial’), a Mitsubishi Trading (classified as ‘commercial’), or a JPMorgan-Chase (classified as ‘financial’) – are capitalized through both debt and equity and therefore pay both interest and profits. The result is that, all else being equal, the higher the debt/equity ratio in a society, the greater the ratio of net interest to profit – regardless of what is being produces or how it is produced. And since both debt and equity are ‘financial’ entities to begin with, the ratio of net interest to profit (or the share of net interest in national income more broadly) can tell us nothing about the degree of ‘financialism’.

Next, consider your proxy for ‘imperialism’. As noted in our original article, the meaning of this term changed several times over the past century. Initially, it was associated with the core states exporting their excess surplus to the periphery (old imperialism); then it was used to describe the core sucking in surplus from the periphery (dependency and world systems); and most recently it has been linked to the core using the financialized liquidity of the periphery to fuel its own asset markets (hegemonic transition).

Obviously, these are very different if not mutually exclusive views. Your own measure – the ratio of net financial services to export earnings – seems consistent, at least nominally, with the dependency/world systems interpretation; that is, with surplus being sucked in from the periphery to the core. This measure, though, doesn’t describe the old imperial investment of core surpluses in the periphery, and it doesn’t account for the hegemonic transition argument in which liquid assets flow from the periphery to the core.

2. Interpretations

Now, in your Figure 6, the two series – U.S. net interest as a share of GDP and the ratio of Argentina’s net financial services to export – follow a pronounced cyclical pattern. If we accept your argument and take the first ratio as a proxy for imperialism and the second for financialism, we would conclude that the two processes crumbled during the 1930s-1940s, soared during the 1950s-1970s and receded again beginning in the 1980s. On the face of it, this description seems consistent with the collapse of colonialism and high finance in the first half of the century, and it certainly sits well with the growth of neo-imperialism since the 1950s and the sprouting of neoliberalism in the 1970s.

But what about the period since the 1980s? According to the theory of hegemonic transition, this period is the pinnacle of financialism – yet your chart shows that both financialism and imperialism have declined.

In our view, the explanation is much simpler. The correlation of the two ratios in your Figure 6 arises not because ‘imperialism’ drives ‘financialism’ or vice versa, but because both ratios are determined by the same underlying processes: (1) the numerators of the two ratios – net interest in the United States and Argentina’s net financial services – move up and down with the rate of interest; and (2) the denominators of the two ratios – U.S. GDP and Argentine exports – move up and down with global growth and contraction.

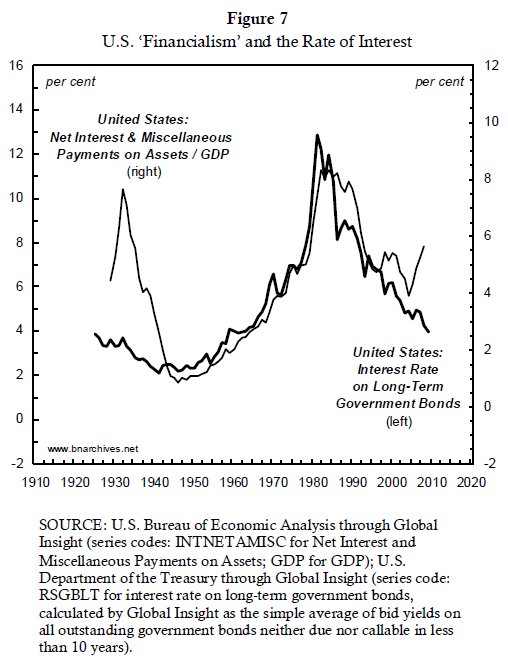

The importance of the rate of interest here is illustrated in Figure 7 and Figure 8. The first of these charts contrasts the U.S. share of net interest and miscellaneous payments on assets in GDP with the long term rate of interest on U.S. government bonds (a proxy for the average rate of interest). The correlation is obvious and trivial: since the amount of outstanding debt changes relatively slowly, the net interest share of GDP tends to be heavily influenced by the rate of interest. Note that the correlation is less pronounced for the 1930s and 1940s. During that period, the depression and subsequent war-induced boom caused GDP to collapse and then soar, and that sharp cycle made the net interest share of GDP fluctuate by much more than the rate of interest.

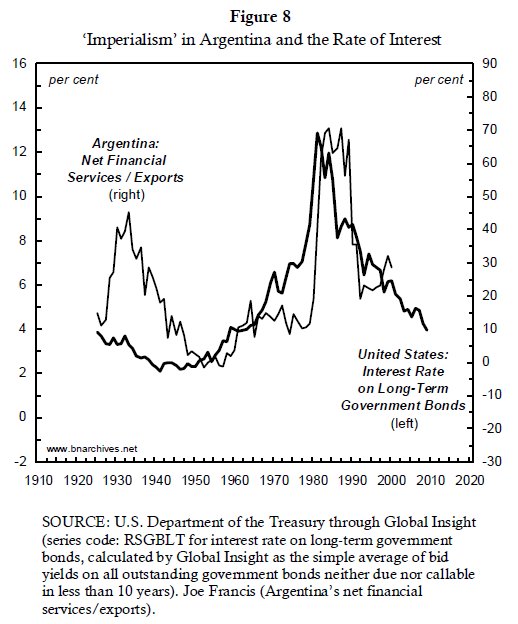

Figure 8 illustrates the same logic with respect to the Argentinean ratio of net financial services to exports (using your own data). During the 1930s and 1940s, Argentinean exports collapsed and boomed with the global cycle, making the ratio of net financial services to export follow the same up and down cycle as the U.S. net interest share of GDP. In the subsequent period, however, the relative changes in interest rates tended to be much larger than the relative changes in both exports and the magnitude of foreign debt; hence the tight correlation between the two series in the chart.

Of course, one could argue that the ups and downs of interest rates, GDP and exports are all facets of imperialism and/or financialism – but that claim would only demonstrate our point that the nexus between them now means everything and nothing. . . .

If we are to preserve Marx’s radical spirit – as both you and we do – then we must be willing to jettison outdated categories, ideologies and methods. We don’t need faith, ritual and myth à la Sorel, and we certainly don’t need habits, conventions and dogmas, whether structuralist or postist. What we do need is a daring, critical science, an open-ended democratic endeavour to re-examine and re-search the capitalist reality – including our own conceptions.

Many thanks for your engagement. It has been a pleasure.

Shimshon and Jonathan

Endnotes

[1] Joe

Francis is a PhD candidate at the London School of Economics (joefrancis505@yahoo.co.uk; http://www.joefrancis.info/). Shimshon

Bichler teaches political economy at colleges and universities in Israel (tookie@barak.net.il; http://bnarchives.net). Jonathan Nitzan

teaches political economy at York University![]() in Toronto (nitzan@yorku.ca; http://bnarchives.net).

in Toronto (nitzan@yorku.ca; http://bnarchives.net).

[2] Giovanni Arrighi (1994) The Long Twentieth Century: Money, Power, and the Origins of Our Times, London & New York: Verso, pp. 301-303.

[3] John Hobson (1902) Imperialism: A Study, 1st edition, New York: James Pott & Co, part 1, ch.4.

[4] Harry Magdoff (1969) The Age of Imperialism: The Economics of U.S. Foreign Policy, New York & London: Monthly Review Press, pp. 35-38, emphasis in original.

[5] Giovanni Arrighi (1997) ‘Financial Expansions in World Historical Perspective: A Reply to Robert Pollin’, New Left Review, Vol.1, No.224, July-August, p. 155.

[6] According to government data, around 80% of foreign investment in Argentina came in the form of imported goods (machinery and unassembled parts) during the first half of the 1960s (Fabricaciones Militares [1965] Síntesis Estadística de Radicaciones de Capitales Extranjeros al 30-6-64, 2nd edition, Dirección de Movilización Industrial).

[7] Jorge Schvarzer (1996) La Industria que Supimos Conseguir, Buenos Aires: Editorial Planeta, p. 290, my translation.

[8] Based on Datastream data that I downloaded towards the end of that year.

[9] See P. Astorga, A.R. Bergés & E.V.K. FitzGerald ‘The Standard of Living in Latin America during the Twentieth Century’, Economic History Review, LVIII, 4 (2005) pp. 765-96.