Capitalism as a Mode of Power

Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan

interviewed by Piotr Dutkiewicz

Jerusalem, Montreal and Ottawa, July 2013

A shorter version of this interview is forthcoming in 22 Ideas to Fix the World: Conversations with the World’s Foremost Thinkers, edited by Piotr Dutkiewicz and Richard Sakwa (New York: New York University Press, WPF and the Social Science Research Council, 2013).

Piotr Dutkiewicz: In a unique two-pronged dovetailing discussion, frequent collaborators and coauthors Jonathan Nitzan and Shimshon Bichler discuss the nature of contemporary capitalism. Their central argument is that the dominant approaches to studying the market – liberalism and Marxism – are as flawed as the market itself. Offering a historically rich and analytically incisive critique of the recent history of capitalism and crisis, they suggest that instead of studying the relations of capital to power we must conceptualize capital as power if we are to understand the dynamics of the market system. This approach allows us to examine the seemingly paradoxical workings of the capitalist mechanism, whereby profit and capitalization are divorced from productivity and machines in the so-called real economy. Indeed Nitzan and Bichler paint a picture of a strained system whose component parts exist in an antagonistic relationship. In their opinion, the current crisis is a systemic one afflicting a fatally flawed system. However, it is not one that seems to be giving birth to a unified opposition movement or to a new mode of thinking. The two political economists call for nothing short of a new mode of imagining the market, our political system, and our very world.

1.

Piotr Dutkiewicz: Let’s start from a fairly general big picture of the economic system. Please look around and tell me what you see as the key features of the current market system.

Shimshon Bichler: Although it may not seem so at first sight, your question is highly loaded. For me to describe the current “economic system” and “market system” is to accept these terms as objective entities, or at least as useful concepts. But are they?

Piotr Dutkiewicz: So what terms would you use? Is there an alternative approach?

Shimshon Bichler: Yes, there is an alternative approach; but before getting to that approach, we need to sort out the problem with the conventional one.

In my view, terms such as the “economic system” and the “market system” are misnomers. They are irrelevant and misleading. Nowadays, they are employed more as ideological slogans than scientific concepts. Those who use them often end up concealing rather than revealing the capitalist reality.

Of course, this wasn’t always the case. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when capitalism was just taking hold, there was nothing apologetic about the market. On the contrary. The market was seen as the harbinger of progress – a powerful institution that heralded liberty, equality and tolerance. “Go into the London Exchange,” wrote Voltaire, “a place more dignified than many a royal court. There you will find representatives of every nation quietly assembled to promote human welfare. There the Jew, the Mahometan and the Christian deal with each other as though they were all of the same religion. They call no man Infidel unless he be bankrupt.”[1]

The market has had a dramatic impact on European history, partly because it emerged in a seemingly unlikely setting. After the nomadic invasions and the fall of the imperial civilization of the first millennium AD, Europe developed a highly fractured social regime we now call feudalism. This regime was based on self-sufficient rural estates, cultivated by peasant-serfs and ruled by a violent aristocracy. Technical knowhow during that period was limited, the agricultural yield meager and trade almost non-existent. The power relations were legitimized by the sanctified notion of a “triangular society,” comprising prayers, warriors and tillers (or, in a more political lingo, priests, nobles and peasants). Merchants and financiers had no place in that scheme.

But not for long. The feudal order began to disintegrate during the first half of the second millennium AD, and this decline was accompanied – and to some extent accelerated – by the revival of trade and the growth of merchant cities such as Bruges, Venice and Florence. These developments signaled the beginning of a totally new social order: an urban civilization that gave rise to a new ruling class known as the “bourgeoisie,” an unprecedented civilian-scientific revolution and a novel culture we now call “liberal.”

Because of the specifically European features of this process, the market came to symbolize the negation of the ancien régime: in contrast to the feudal order which was seen as collective, stagnant, austere, ignorant and violent, the market promised individualism, growth, well-being, enlightenment and peace. And it was this early conflict between the rule of feudalism and the aspirations of capitalism that later galvanized into what most people today take as a self-evident duality: the contrast between the state, or “politics,” and the market, or the “economy.”

According to this conventional bifurcation, the economy and politics are orthogonal realms, one horizontal and the other vertical. The economy is the site of independence, productivity and well-being. It is the clearing house for individual wants and desires, the voluntary arena where autonomous agents engage in production and exchange in order to better their lives and augment their utility. By contrast, the political system of state organizations and institutions is the locus of control and power. Unlike the flat structure of the free economy, politics is hierarchical. It is concerned with coercion and oppression and driven by command and obedience.

In this scheme, the economy – or more precisely, the “market economy” – is considered productive (generating wealth), efficient (minimizing cost) and harmonious (tending toward equilibrium). It is competitive (and therefore free). It seeks to increase well-being (by maximizing utility). And if left to its own device (laissez faire), it augments the welfare of society (by sustaining economic growth and increasing the wealth of nations). The political system, by contrast, is wasteful and parasitical. Its purpose is not production, but redistribution. Its members – the politicians, state officials and bureaucrats – seek power and prestige. They eagerly “intervene” in and “monopolize” the economy. They tax, borrow and spend – and in the process stifle the economy and “distort” its efficiency. Sometimes, “externalities” and other forms of “market failure” make state intervention necessary. But such intervention, the argument goes, should be minimal, transitory and subjugated to the overarching logic of the economy.

Piotr Dutkiewicz: So the “market” serves the role of a new ideology for the bourgeoisie?

Shimshn Bichler: Exactly. The portrayal I’ve just painted owes much to Adam Smith, the eighteenth-century Scotsman who turned the idea of “the market” into the key political institution of capitalism. Smith’s invention helped the bourgeoisie undermine and eventually topple the royal-princely state, and that was just for starters. Soon enough, the market became the chief ideology of the triumphant capitalist regime. It helped spread capitalism around the world, and it assisted in the fight against competing regimes, such as fascism and communism. In the Soviet Union, where production was besieged by chaotic planning and accompanied by tyrannical rule, organized violence, open corruption and restricted consumption, the market symbolized the “other life.” It was the alternative world of freedom and abundance. And this perception is still hammered home by the ideologues of capitalism. In the final analysis, we are told, there are only two options: the market or the Gosplan. If we don’t choose egocentrism and liberty, we end up with planning and tyranny. And that is it. There is no other alternative, or so goes the dogma.

The ideological basis of these arguments was bolstered in the late nineteenth century by the official split of classical political economy into two distinct academic disciplines – political science and economics. The term “economics” was invented by Alfred Marshall, the Cambridge University don who coined it to denote the new “marginalist,” or neo-classical, doctrine of political economy. Marshall, who wanted economics to be a real science, gave it the same suffix as that of physics and mathematics. He also wrote the first economics textbook (the definitive edition of which was issued in 1890), where he set the rigid boundaries of the discipline, elaborated its deductive format and articulated many of the examples that are still being used today.

Despite its aspirations, though, economics never became a real science, and for a simple reason: it couldn’t. Science is skeptical. Unlike organized religion, which is infinitely confident, science thrives on doubt. It relies not on static ritual and unchanging dogma, but on seeking novel explanations for ever-expanding horizons. It tries to understand, not to justify. Now, none of this could be said about economics. If anything, we can say the very opposite: the latent role of economics was not to explain capitalism, but to justify it. When economics first emerged in the late nineteenth century, capitalism was already victorious. But it was also highly turbulent and increasingly contested by critiques and revolutionaries, so it had to be defended; and the ideological part of that defense was delegated to the new priests of liberalism: the economists. In order to perform their role, the economists have elaborated an intricate system of mathematical models. This system, they claim, proves that a free, totally unregulated economy – if we could ever have one – would yield the best of all possible worlds, by definition.

The conventional counterclaim, marshaled by many heterodox critiques, is that neoclassical models may be elegant, but they have little or nothing to do with the actual world we live in. And there is certainly much truth in this observation. But the “science of economics” is besieged by a far deeper problem that rarely if ever gets mentioned: it relies on fictitious quantities.

Every science rests on one or more fundamental quantities in which all other magnitudes are denominated. Physics, for example, has five fundamental quantities – length, time, mass, electrical charge and heat – and every other measure is derived from those quantities. For instance, velocity is length divided by time; acceleration is the time derivative of velocity; and gravity is mass multiplied by acceleration. Now, as a science, economics too has to have fundamental quantities – and the economists claim it does. The fundamental quantity of the neoclassical universe is the unit of hedonic pleasure, or “util.”

Piotr Dutkiewicz : Can you explain this idea in more detail? How does the “util” form the basis of the neoclassical economic universe?

Shimshon Bichler: The answer begins with the conventional bifurcation of the economy itself into two quantitative spheres: “real” and “nominal.” According to the economists, the key is the real sphere. This is the material engine of society, the realm of tangible assets and technical know-how, the locus of production and consumption, the fountain of well-being. The nominal side of the economy is secondary. This is the sphere of money, prices and finance, of inflation and deflation, of speculative bubbles and stock market crashes. Although highly dynamic, the nominal sphere doesn’t have a life of its own. Its money magnitudes are merely reflections – sometimes accurate sometimes inaccurate – of what happens in the real sphere. And the reflection is quantitative: the price quantities of the “nominal” spheres mirror the substantive quantities of the “real” sphere.

Now, in the final analysis, all economic quantities are reducible to utils. The util is the elementary particle of economic science. It is the fundamental quantity, the basic building block everything economic is made of. The utils themselves, like Greek atoms, are identical everywhere, but their combination yields infinitely complex forms that economists call “goods and services.” Every composite of the “real economy” – from the aggregate quantities of production, consumption and investment, to the size of GDP, to the magnitude of military spending and the scale of technology – is the sum total of the utils it generates. And the price magnitudes of the “nominal” economy – for instance, the dollar prices of an industrial robot (say $5 million) and a trendy iPhone ($500) – merely represent and reflect the util-denominated quantities of their respective “real” quantities (whose ratio, assuming the reflection is accurate, is 10,000:1).

And, yet, and here we come to the crux of the matter, this util – this basic quantum that everything economic is supposedly derived from – is immeasurable and in fact unknowable!

Nobody has been able to identify the quantum of a util, and I very much doubt that anyone ever will. It is a pure fiction. And since all “real” economic quantities are denominated in this fictitious unit, it follows that their own quantities are fictitious as well. To measure “real GDP” or the “standard of living” without utils is like measuring velocity without time, or gravity without mass. (I should note here that a similar critique can be leveled against classical Marxism. The elementary particle of the Marxist universe is socially necessary abstract labor. This is the fundamental quantity that all “real” magnitudes are made of and which the nominal spheres (should) reflect – and yet no Marxist has ever measured it.)

So, just like in Andersen’s The Emperor’s New Clothes, everyone pretends. The students, dazed by the endless drill of “practical” assignments, do not even suspect that their “computations” are practically meaningless. Most professors, having graduated from the meat grinder of neoclassical training, have had all traces of the problem safely erased from their memory (assuming they were aware of it in the first place). And the statisticians, whose job is to measure the economy, have no choice but to concoct numbers based on arbitrary assumptions that nobody can either validate or refute. The entire edifice hangs in thin air, and everyone keeps quite lest it collapse.

Piotr Dutkiewicz: So what you are saying is that one of the very few supposedly solid foundations of our life – the notion that something “economic” is measurable and thus “objective” – is a fiction?

Shimshon Bichler: Yes. And this, mind you, is the dominant ideology that rules the world.

Every cog in the corporate-government-military megamachine – from business managers and state planners, through army officers and central bankers, to financial analysts, accountants and tax experts – is hardwired to the conventions and rituals of this doctrine. They are all conditioned by the same never-to-be-questioned mantras of the capitalist matrix: that the economy is productive and politics parasitic; that the market is equilibrating and the state destabilizing; and, of course, that we constantly need to check the excesses of government, deregulate the economy and increase competition.

So if we come back to your original question, I cannot characterize contemporary reality in terms of its “economy” and the “market system.” These are misleading categories to begin with. They force us into a rigid neoclassical template, block our vision and stifle our imagination. They make creative thinking all but impossible. If we want to transcend these barriers and think openly, the first thing we need to do is dispense with these categories altogether.

And this is the time to do so. We live in a deep crisis, and deep crises can sometime lead to an intellectual renaissance. They tend to foster critical thinking, generate novel methods of inquiry and help us devise alternative forms of action. The Great Depression of the 1930s triggered such a revival. That crisis transformed the way we understand and critique society: it gave birth to liberal “macro” economics and anti-cyclical government policy; it rejuvenated Marxist and other streams of radical thinking in areas ranging from political economy to philosophy to literature; and, by shattering many of the prevailing dogmas, it allowed the mutual insemination of ideologically opposing approaches.

Piotr Dutkiewicz: Some say that the 2007-2009 crisis was indeed a trigger for such a reevaluation, but are we actually seeing any real change in the way the economy is perceived?

Shimshon Bichler: I don’t think so. One would have expected a revival similar to that which followed the Great Depression in the current crisis, but so far the signs of such a revival are nowhere to be seen. A small chorus of mainstream economists such as Nouriel Rubini, Joseph Stilglitz and Paul Krugman have criticized their discipline. But besides moral indignation and contrarian predictions, their critiques offer nothing that is fundamentally new. The real disappointment, though, is the theoretical weakness of the left. During the 1930s, radical movements and organizations were energized by novel theories of capitalism and detailed platforms for its replacement. That isn’t the case today. The anti-globalization, ecology and Occupy movements lack this source of energy. They don’t have a new theoretical foundation to build on – and without such a foundation, they find it hard to develop an effective critique of capitalism, let alone a clear alternative that would come in its stead.

This weakness creates a vacuum that is increasingly filled by religious and radical right movements. And with the global crisis ongoing and the ruling class tittering on the verge of panic, there is a real possibility of a massive shift to the right, not unlike that of the 1930s. I think that such a shift will be difficult to prevent, let alone counteract and reverse, without a totally new theoretical alternative.

2.

Piotr Dutkiewicz: In light of Shimshon Bichler’s insights into the ideological role of economic theory, is it still relevant to talk about capital, capitalism, and capitalist culture? It sounds as if we are back in the nineteenth century.

Jonathan Nitzan: I think these terms remain relevant. Our world, of course, is rather different from that of the nineteenth century, but it is still very much capitalistic. In fact, it is more capitalistic that it ever was.

When we were growing up in the 1950s, we rarely heard words such as “capitalist”, “capitalism” and the “capitalist regime.” They sounded like anachronistic remnants of a bygone era. They might have been relevant to the cruel reality of Victorian England that Marx experienced and analyzed, or to old communist propaganda banners, but not to the middle of the twentieth century. By the 1950s, Victorian England was a very distant memory, and communist parties seemed to be losing their proletarian appeal to the tide of rising wages. The terminology of classical political economy, having become useless, sank into oblivion.

This was the heyday of the Cold War, and the dominant ideology emphasized the wonders of “modernization.” The old colonial system was disintegrating, the Western welfare-warfare state was expanding, and many workers no longer lived at subsistence levels. Instead of the “class struggle,” the pundits started talking about an “affluent society.” There was no longer any need, they argued, for the dialectics of Marx’s historical materialism. The positivist path of Auguste Comte offered a much more efficient and just method of managing industrial society.

It was therefore surprising to witness the recent revival of “capital” and “capitalism.” The terms first reappeared in mainstream lingo after the collapse of communism in the late 1980s, and within less than a decade they were already commonplace in academic writings and popular discourse. This time around, though, they were used not as ideologically contestable concepts, but as part of the natural order of things. As Michel Houellebecq observes in The Possibility of an Island, for most of those born into the neoliberal order, protesting layoffs or economic policy, let alone the regime itself, seems as absurd as protesting weather changes or locust infestations. The contemporary global natives can imagine no meaningful alternative to the capitalist order, and the rulers know it. Their oppressive tolerance has helped assimilate the critique of capitalism into its own mass culture, as Herbert Marcuse so eloquently anticipated in his One-Dimensional Man.

Piotr Dutkiewicz: So does that mean that capitalism has somehow become a misleading slogan?

Jonathan Nitzan: Not at all. The term still represents the world we live in. When Marx invented the notion of the “capitalist regime,” he referred not to the narrow economic domain or even to liberal ideology more broadly. For him, the capitalist regime denoted a new totalizing logic, a material-ideal system that dominates society and governs its historical trajectory. Individuals in this scheme, whether they are workers or capitalists, are secondary. Regardless of where they are situated in society, they all obey the same supreme subject: capital itself. The logic of capital affects everything. It dictates the nature of ownership, power and authority, it influences the technological process and it shapes human consciousness. It seems to me that this broad description of the rule of capital, a condition that Marx was the first to identify and describe, is more valid today than it ever was.

Piotr Dutkiewicz: So is capitalism a constant, making evolution a frivolous concept? In the dynamic picture of European politico-social systems you have written about with Bichler, is capitalism the only “unchangeable element”?

Jonathan Nitzan: What has changed, I think, and dramatically so, is the specific nature of capitalism. Marx’s science and the bourgeois political economy he criticized were creatures of their time. Both were informed by the apparent separation of the sweatshops, factories and “civil society” of merchants and industrialists on the one hand from the ancient statist-political regime on the other. Both were impressed by the atomistic nature of capitalism, its anarchic competition, the disciplinary role of technology and the apparent automaticity of the system’s cyclical gyrations and long-term tendencies. And both were marked by the scientific revolution from which they emerged: the demand and supply of the liberals reproduced Newton’s forces of attraction and repulsion, while Marx’s historical laws of motion paralleled the new cosmology of the heavenly bodies; their equilibrium and disequilibrium tendencies replicated Newton’s duality of inertia and force; and their analytical methods employed the new techniques of calculus, probability and statistics.

However, by the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the classical portrayal and analysis of capitalism no longer seemed valid. There were several reasons for this growing mismatch. First, the rise and expansion of large organizational units – from big business to big government to big unions – made it difficult to speak of an atomistic society, let alone of its automatic regulation. Second, there emerged a whole slew of new processes – from total war and the permanent war economy, through large-scale government policies, to the growth of a “labor aristocracy” and leisure time, corporate management, inflation and large-scale financial intermediation – that the classical political economists were completely unfamiliar with and that their old theoretical schemes could not accommodate. Third, with the rise of fascism and Nazism, the primacy of class and production was challenged by a new emphasis on masses, power, state, bureaucracy, elites and systems. And fourth, the objective/mechanical cosmology of the first political-scientific revolution was undermined by uncertainty, relativity and the entanglement of subject and object. Science, including the science of society, was increasingly challenged by anti-scientific vitalism and postism.

These developments resulted in a deep rupture: while capitalism has become ever more universal, the unified theory that once explained it has disintegrated. Bourgeois political economy has been divided and subdivided. Instead of a single study of capitalism, we now have a multitude of distinct disciplines – economics, politics, sociology, psychology, anthropology, international relations, management, finance, culture, gender, communication and what not – all trying to barricade their own turf and protect their proprietary categories. The same has happened with classical Marxism: what once stood as a totalizing critique of capitalism has been fractured into a tripod of neo-Marxian economics, a neo-Marxian critique of culture and neo-Marxian theories of the state. And if this wasn’t bad enough, in between all the cracks emerged the rapidly multiplying anti-science dogmas of “post-modernity” that deny the possibility of a universal logic altogether.

Piotr Dutkiewicz: What would your solution be to these fragmented approaches toward something that governs the very way we live, earn, spend, and accumulate?

Jonathan Nitzan. I think we can no longer rely on the prevailing theories and dogmas. They are fractured and exhausted. If we wish to change society, we ought to embark on a totally new path. And the first step in that path is to revolutionize the way we understand capitalism. The grip of capital is universalizing, and so should our attempt to comprehend and counteract it be. We need theories and research methods that are not disjoined and fractured, but encompassing and totalizing. And in devising these theories and methods, we should focus not on the world of yesterday, but on the capitalist reality of today and, indeed, tomorrow.

3.

Piotr Dutkiewicz: Even neoliberals agree that we need to reinvent or reinforce political economy, as we have lost a vital link between politics and the market. So what should be the centerpiece of today’s political economy?

Shimshon Bichler: The centerpiece is still capital, but we have to think about it in a totally new way. Capital is not means of production that generate hedonic pleasure as the liberals argue, and it is not a quantum of abstract labor as the Marxists claim. Rather, capital is power, and only power.

Note the emphasis on the word “is.” Capital, Jonathan Nitzan and I claim, should be understood not in relation to or in association with power, but as power. This figurative identity is very different from the conventional creed. Marxist and mainstream analysts often connect capital with power. They say that capital “affects” power, or that it is “influenced” by power; that power can help “augment” capital, or that capital can “increase” power, etc. But these are all external relations between distinct entities. They speak of capital and power, whereas we talk about capital as power.

Further, and more broadly, we argue that capitalism is best viewed not as a mode of production or consumption, but as a mode of power. Machines, production and consumption of course are part of capitalism, and they certainly feature heavily in accumulation. But the role of these entities in the process of accumulation, whatever it may be, is significant only insofar as it bears on power.

To explain our argument, let me start with two basic entities: prices and capitalization. Capitalism – as both liberals and Marxists recognize – is organized as a numerical commodity system denominated in prices. The capitalist regime is particularly conducive to numerical organization because it is based on private ownership, and anything that can be privately owned can be priced. This basic feature means that, as private ownership spreads spatially and socially, price becomes the universal numerical unit with which the capitalist order is organized.

Now, the actual pattern of this numerical order is created through capitalization. Capitalization, to paraphrase physicist David Bohm, is the “generative order” of capitalism. It is the flexible, all-inclusive algorithm that continuously creorders – or creates the order of – capitalism.

Piotr Dutkiewicz: What exactly is capitalization?

Shimshon Bichler: Considered most broadly, capitalization is a symbolic financial entity; it is the ritual that capitalists use to discount risk-adjusted expected future earnings to their present value. This ritual has a very long history. It was first invented in the proto-capitalist bourgs of Europe during the fourteenth century, if not earlier. It overcame religious opposition to usury in the seventeenth century to become conventional practice among bankers. Its mathematical formulae were first articulated by German foresters in the mid-nineteenth century. Its ideological and theoretical foundations were laid out at the turn of the twentieth century. It started to appear in textbooks around the 1950s, giving rise to a process that contemporary experts refer to as “financialization.” And by the early twenty-first century, it has grown into the most powerful faith of all, with more followers than of all the world’s religions combined.

Nowadays, capitalists – as well as everyone else – are conditioned to think of capital as capitalization, and nothing but capitalization. The ultimate question here is not the particular entity that the capitalist owns, but the universal worth of this entity defined as a capitalized asset.

Piotr Dutkiewicz: And how does this mechanism of capitalization actually work?

Shimshon Bichler: Take the example of a capitalist who considers buying (or selling) an Exxon share with expected annual earnings of $100. If the discount rate is 10%, or 0.1, the capitalist will capitalize the asset at $1,000 (to verify, expected earnings of $100 on a $1,000 investment represent an expected return of 10%, or 0.1). The expected earnings themselves are partly objective, partly subjective. The objective part is the actual earnings that will become known in the future, say $50. But the capitalist in our example expects $100, meaning that he or she is overly optimistic. We call this over-optimism “hype,” and this hype has a quantity – in this case, 2 (=$100/$50). If the capitalist were overly pessimistic, with a hype of say ½, the expected earnings would be only $25. The discount rate is also made of two components: the normal rate of return – say the yield on relatively safe Swiss governments bonds – and a risk assessment. In our case, the normal rate of return may be 5%, but if Exxon is assessed to be twice as risky as Swiss government bonds, the discount rate will be twice as high, at 10% (=2 x 5%).

Neoclassicists and Marxists recognize the existence of capitalization – but given their view that capital is a “real” economic entity, they don’t quite know what to do with its symbolic appearance. The neoclassicists bypass the impasse by saying that, in principle, capitalization is merely the mirror image of real capital – although, in practice, this image gets distorted by unfortunate market imperfections. The Marxists approach the problem from the opposite direction. They begin by assuming that capitalization is entirely fictitious – and therefore unrelated to the actual, or real capital. But, then, in order to sustain their labor theory of value, they also insist that, occasionally, this fiction must either inflate or crash into equality with real capital.

It seems to me that these attempts to make capitalization fit the box of real capital are an exercise in futility. First, as I already noted, “real” capital lacks an objective quantity. And, second, the very separation of economics from politics – a separation that is necessary to make such objectivity possible in the first place – has become defunct. And, indeed, capitalization is hardly limited to the so-called economic sphere.

Every stream of expected income is a candidate for capitalization. And since income streams are generated by social entities, processes, organizations and institutions, we end up with capitalization discounting not the so-called sphere of economics, but potentially every aspect of society. Human life, including its social habits and its genetic code, is routinely capitalized. Institutions – from education and entertainment to religion and the law – are habitually capitalized. Voluntary social networks, urban violence, civil war and international conflict are regularly capitalized. Even the environmental future of humanity is capitalized. Nothing escapes the eyes of the discounters. If it generates expected future income, it can be capitalized, and whatever can be capitalized sooner or later is capitalized.

The encompassing nature of capitalization calls for an encompassing theory, and the unifying basis for such a theory is power. The primacy of power is built right into the definition of private ownership. Note that the English word “private” comes from the Latin privatus, which means “restricted.” In this sense, private ownership is wholly and only an institution of exclusion, and institutionalized exclusion is a matter of organized power.

Of course, exclusion does not have to be exercised. What matters here are the right to exclude and the ability to exact pecuniary terms for not exercising that right. This right and ability are the foundations of accumulation.

Capital, then, is nothing other than organized power. This power has two sides: one qualitative, the other quantitative. The qualitative side comprises the institutions, processes and conflicts through which capitalists constantly creorder society, shaping and restricting its trajectory in order to achieve their redistributive ends. The quantitative side is the process that integrates, reduces and distils these numerous qualitative processes down to the universal magnitude of capitalization.

4.

Piotr Dutkiewicz: Let me raise a very broad question: What is power? Can power be an economic force? What is the link between power and capital? We are used to thinking about capital as an exclusively economic category, but you seem to understand it differently. How exactly do you understand it? What are the more practical consequences of your approach to understanding current economic-cum-political systems?

Jonathan Nitzan. As Hegel tells us in The Phenomenology of Mind and elsewhere, and as Max Jammer shows in his Concepts of Force, power is not a thing in itself. It is a relationship between things. Consequently, power cannot be observed as such. We know it only indirectly, through its effects. In religion, the power of the gods is revealed through their alleged deeds and miracles, while in science power is revealed through its measureable consequences. We know of gravity not by observing it directly, but by measuring the quantitative relationship between mass and acceleration. Similarly with capital as power: we know the power of owners indirectly, by the numerical magnitude of their capitalization and the way in which it creorders society.

Piotr Dutkiewicz: And how does capitalist power creorder society?

Jonathan Nitzan: To answer this question, we first need to make a distinction between the creative/productive potential of society – the sphere that the American political economist Thorstein Veblen called industry – and the realm of power that, in the capitalist epoch, increasingly takes the form of business. This distinction is crucial not least because it goes counter to the conventional creed: in common parlance, industry and business are synonyms, whereas for Veblen they were antonyms.

Using as a metaphor the concept of physicist Denis Gabor, we can think of the social process as a giant hologram, a space crisscrossed with incidental waves. Each social action – whether an act of industry or of business – is an event, an occurrence that generates vibrations throughout the social space. However, there is a fundamental difference between the vibrations of industry and the vibrations of business. Industry, understood as the collective knowledge and creative effort of humanity, is inherently cooperative, integrated and synchronized. It operates best when its various events resonate with each other. Business, in contrast, isn’t collective; it’s private. Its goals are achieved through the threat and exercise of systemic prevention and restriction – that is, through what Veblen called strategic sabotage. The key object of this sabotage is the resonating pulses of industry – a resonance that business constantly upsets through built-in dissonance.

Business sabotage affects both the direction and pace of industry. The impact on the direction of industry is so prevalent that we often don’t see it. The most obvious effect is the progressive subjugation of billions of minds and bodies to the single-minded Moloch of profit-making and the consequent stifling of individual and societal creativity. And that is just the beginning. Consider the following examples: the systematic destruction of public transportation in the United States and elsewhere in favor of the ecologically disastrous private automobile; the development by pharmaceutical companies of expensive remedies for concocted “medical conditions” instead of drugs to cure real diseases that mostly afflict those who are too poor to pay for treatment; the promotion by global conglomerates of junk food in lieu of a healthy diet; the imposition of intellectual property rights on societal knowledge instead of the free diffusion of such knowledge; the invention by high-tech companies of weapon technologies instead of alternative clean and renewable energies; the development by chemical and bio-technology corporations of one-size-fits-all genetically modified plants and animals instead of bio-diversified ones; the forced expansion by governments and realtors of socially fractured suburban sprawl instead of participatory and sustainable urbanization; the development by television networks of lowest-common-denominator programming that sedates the mind rather than stimulates its critical faculties; the list goes on.

These and similar diversions permeate the entire structure of capitalism. They can be seen everywhere – that is, provided we are willing take off our neoclassical blinkers. And if we accounted for them all, we would have to conclude that a significant proportion of business-driven “growth” is wasteful, not to say destructive, and that the sabotage that underlies this waste and destruction is exactly what makes it so profitable.

The other form of business sabotage is the impact it has on the pace of industry. Conventional political economy, both neoclassical and Marxist, postulates a positive relationship between production and profit. Capitalists, the argument goes, benefit from industrial activity and, therefore, the more fully employed their equipment and workers, the greater their profit. But if we think of capital as power, exercised through the strategic sabotage of industry by business, the relationship should be nonlinear – positive under certain circumstances, negative under others.

And that is exactly what the historical data tell us. In the United States, Great Britain and Canada, for example, the share of capitalists in national income (measured by profit plus interest) has tended to rise as growth accelerated and the rate of unemployment declined – but only up to a point. After that point, rising growth and declining unemployment – in other words, less sabotage – have tended not to increase but to reduce the income share of capitalists!

The case of the United States is illustrative. In the 1930s, when the sabotage of industry by business was extreme and official unemployment hovered around 25%, the share of capitalists in national income stood at around 11%. Then came the Second World War, employment and production soared, and the income share of capitalists rose to nearly 16%. But that was the peak. As the war effort continued, business sabotage of industry was almost eliminated and unemployment fell to less than 2%. However, the share of capital in national income, instead of rising as conventional political economy would have predicted, dropped sharply, reaching a low of 12%, barely above its depression level. This situation was obviously unacceptable to capitalists; so after the war, sabotage was reinstated, unemployment rose to between 5 and 7%, and capitalists’ share in national income soared to an all-time high of nearly 19%. It seems that “business as usual” (high capitalist income) and the “natural rate of unemployment” (the strategic level of industrial sabotage) are two sides of the same capitalist coin. Perhaps this combination is what economists have in mind when they speak about equilibrium.

Piotr Dutkiewicz: Can you further concretize the notion of capital as power? How is this concept related to what economists call “profit maximization”? What does it tell us that standard economics and other social sciences do not?

Jonathan Nitzan: Power is never absolute; it’s always relative. For this reason, Shimshon Bichler and I argue, both the quantitative and qualitative aspects of capital accumulation have to be assessed differentially, relative to other capitals. Contrary to the claims of conventional economics, capitalists are driven not to maximize profit, but to “beat the average” and “exceed the normal rate of return.” Their entire existence is conditioned by the need to outperform, by the imperative to achieve not absolute accumulation, but differential accumulation. And this differential drive is crucial: to beat the average means to accumulate faster than others; and since the relative magnitude of capital represents power, capitalists who accumulate differentially increase their power – that is, their broad strategic capacity to inflict sabotage.

The centrality of differential accumulation, we claim, means that in analyzing accumulation we should focus not only on capital in general, but also – and perhaps more so – on dominant capital in particular: that is, on the leading corporate-governmental alliances whose differential accumulation has gradually been placed at the center of the political economy.

The importance of this process can be illustrated by the recent history of the United States. Over the past half century or so, differential accumulation by U.S. dominant capital has advanced in leaps and bounds. In 1950, the average net profit per firm among the top 100 U.S.-incorporated companies was roughly 1,600 times larger than the average net profit per firm in the U.S. business sector as a whole; by 2010, this multiple was fourteen-fold larger, at over 23,000!

This massive increase in differential accumulation quantifies the growing power of U.S. dominant capital; the other side of this trend is the qualitative power processes that differential accumulation quantifies and distils into a single magnitude. Much of our work over the past three decades has been devoted to examining this quantitative-qualitative underpinning of power, in the United States and elsewhere.

Piotr Dutkiewicz: Can you illustrate this type of analysis? How do its conclusions differ from those of conventional social science?

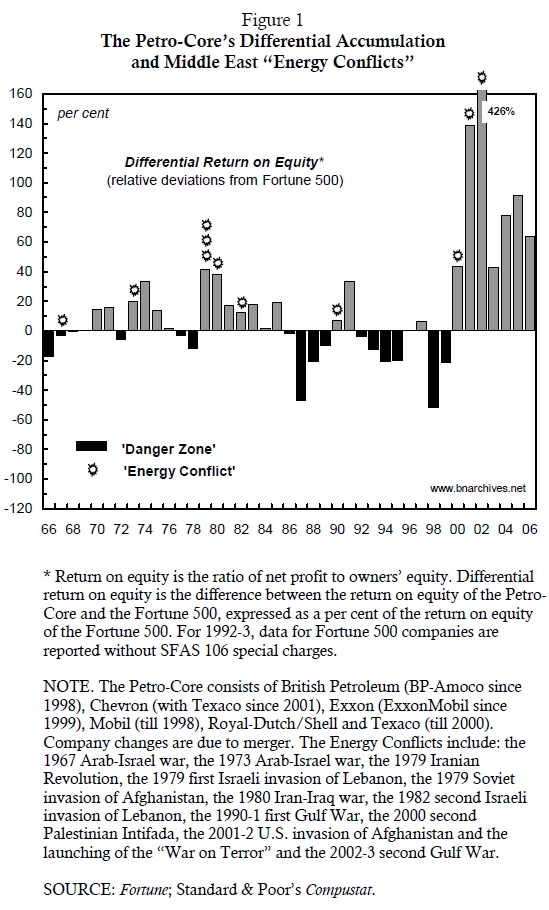

Jonathan Nitzan: Let me take an example from the work Shimshon Bichler and I did on the global political economy of the Middle East. Figure 1 depicts the differential performance of the world’s six leading privately owned oil companies relative to the Fortune 500 benchmark. Each bar in the figure shows the extent to which the oil companies’ rate of return on equity exceeded or fell short of the Fortune 500 average. The gray bars show positive differential accumulation – i.e. the percent by which the oil companies exceeded the Fortune 500 average. The black bars show negative differential accumulation; that is, the percent by which the oil companies trailed the average. Finally, the explosion signs in the chart show the occurrences of “energy conflicts” – a term we use to denote regional energy-related wars.

Now, conventional economics has no interest in the differential profits of the oil companies, and it certainly has nothing to say about the relationship between these differential profits and regional wars. Differential profit is perhaps of some interest to financial analysts. Middle East wars, in contrast, are the business of international relations experts and security analysts. And since each of these phenomena belongs to a completely separate sphere of society, no one has ever considered linking them in the first place. And yet, as it turns out, these phenomena are not simply linked. In fact, they could be thought of as two sides of the very same process – namely, the global accumulation of capital as power.

To get a sense of this process, consider the following relationships evident in the chart. First, every energy conflict was preceded by the large oil companies trailing the average. In other words, for an energy conflict to erupt, the oil companies first had to differentially decumulate – a most unusual prerequisite from the viewpoint of any social science.

Second, every energy conflict was followed by the oil companies beating the average. In other words, war and conflict in the region – processes that social scientists customarily blame for “distorting” the aggregate economy – have served the differential interest of certain key firms at the expense of other key firms.

Third and finally, with one exception, in 1996-7, the oil companies never managed to beat the average without there first being an energy conflict in the region. In other words, the differential performance of the oil companies depended not on production, but on the most extreme form of sabotage: war.

It seems to me that these relationships, and the conclusions they give rise to, are nothing short of remarkable. First, the likelihood that all three patterns are the consequence of a statistical fluke is negligible; there must be something very substantive behind the connection of Middle East wars and global differential profits. Second, these relationships seamlessly fuse quality and quantity. In our research on the subject, we have shown how the qualitative aspects of international relations, superpower confrontation, regional conflicts and the activity of the oil companies on the one hand, can both explain and be explained by the quantitative global process of capital accumulation on the other. And, third, all three relationships have remained stable for half a century, allowing us to predict, in writing and before the events, both the first and second Gulf Wars.[2] This stability tells us that the patterns of capital as power – although subject to historical change from within society – are anything but haphazard.

5.

Piotr Dutkiewicz: Let’s turn to the economic downturn of 2008–9. We used to hear that it is natural, after the boom like the one we had in the past twenty years, to have a downturn. Given the supposedly cyclical nature of the market system, we should theoretically not worry. But from consumers to bankers, we are all worried. So what is different now?

Shimshon Bichler: In light of what was said so far, I think that what we are experiencing now is not an “economic downturn,” or even an “economic crisis,” but a systemic crisis: a crisis that threatens the very existence of the capitalist mode of power. This crisis has been lingering for more than a decade. It started not in 2008, as most observers argue, but in 2000, and it shows no sign of abating.

Piotr Dutkiewicz: Can you further clarify what you mean by “systemic crisis”?

Shimshon Bichler: Let me take for a moment the viewpoint of the capitalists. As they see it, the key barometer of success and failure is not the growth of production or the level of employment, but the movements of the stock market. The stock market capitalizes their expected future earnings – and by so doing distils and reduces their collective view on the future of capitalism down to a single number.

Now, if we examine the history of the U.S. stock market, measured by the S&P 500 price index, we see that, over the past century or so, capitalists were besieged by four “major bear markets.” Each of these major bear markets was characterized by a massive drop in prices, ranging between 50% and 70% in “constant dollars.” Note, however, that these declines, although roughly similar in quantity, were very different in quality. Each of them signaled a major – and unique – creordering of capitalist power:

1. The crisis of 1906-1920 (–70%) marked the closing of the American frontier, the shift from robber-baron capitalism to large-scale business enterprise and the beginning of synchronized finance.

2. The crisis of 1929–1948 (–56%) signaled the end of “unregulated” capitalism and the emergence of large governments and the welfare-warfare state.

3. The crisis of 1969–1981 (–55%) marked the closing of the Keynesian era, the resumption of worldwide capital flows and the onset of neoliberal globalization.

4. And the current crisis – which, as I noted, began not in 2008, but in 2000, and is still ongoing (–50% from 2000 to 2009) – seems to mark yet another shift toward a different form of capitalist power, or perhaps a shift away from capitalist power altogether.

The current crisis is marked by systemic fear. Capitalists today are not just uncertain or worried; they are scared. Their apprehension is not about this or that aspect of capitalism, but about capitalism’s very existence. Many of them now fear that the capitalist order itself may not survive, at least not in its current form.

Piotr Dutkiewicz: What indication do we have that capitalists suffer from “systemic fear”?

Shimshon Bichler: A key gauge of this systemic fear is the way in which capitalists price their equities. The capitalization ritual is unambiguous: it instructs capitalists to discount not the current level of profit, but its estimated long-term trajectory. So, under normal circumstances, changes in stock prices should show little or no direct correlation with changes in current profit – and, indeed, they usually don’t. But periods of systemic fear are anything but normal. During such periods, capitalists doubt the survival of their system, and that doubt makes them lose sight of its future; with the capitalist future having become opaque, the “long-term profit trend” loses its meaning; and with no estimates of long-term profits, capitalists are left with nothing to discount.

In a capitalized world, the inability to capitalize is a mortal threat. So capitalists, desperate for something to hang on to, abandon their sanctified reliance on the expected future and latch onto the present. Numbed by systemic fear, they discount not the eternal long-term trend of profit, but its day-to-day variations. And that is exactly what we observe in the current crisis: since 2000, equity prices, instead of moving independently of current profits, have tracked those profits remarkably closely.

This type of panic-driven breakdown is not unprecedented, though. It also happened in the 1930s. Much like today, capitalists in the 1930s were struck by systemic fear; and much like today, they abandoned the capitalization ritual. Moreover, and crucially, the reason for the breakdown was pretty much the same: in both periods, capitalist power had become so great that capitalists lost confidence that they could retain that power, let alone increase it.

Piotr Dutkiewicz: This claim seems counterintuitive: shouldn’t capitalists be more confident the more powerful they become?

Shimshon Bichler. Only up to a point. Capitalist power is distributional, measured by relative capitalization, so a capitalist group with $300 billion in net assets is three times as powerful as a group with only $100 billion. Now, in beating the average and exceeding the normal rate of return, dominant capital accumulates differentially; and since capital is distributional power, differential accumulation is the augmentation of distributional power. Distributional power, though, is clearly bounded. No group of capitalists, no matter how sophisticated and ruthless, can ever own more than everything there is to own in society. Moreover, in practice, capitalist power is likely to stall long before it reaches this upper limit.

The reason is rooted in the conflictual dynamics of power. Capitalists cannot stop seeking more power: since capital is power, the drive to accumulate is a drive for more power, by definition. But that very quest for power generates its own barriers. Power hinges on the use of force and sabotage, so the closer capitalist power gets to its limit, the greater the resistance this force and sabotage elicit; the greater that resistance, the more difficult it is for those who hold power to increase it further; the more difficult it is to increase power, the greater the need for even more force and sabotage; and the more force and sabotage, the higher the likelihood of a serious backlash, followed by a decline or even disintegration of power.

It is at this latter point, when power approaches its societal “asymptotes,” that capitalists are likely to be struck by systemic fear – the fear that the power structure, having become top heavy, is about to cave in. And it is at this critical moment, when capitalists fear for the very survival of their system, that their forward-looking capitalization is most prone to collapse.

In the United States, this type of collapse was trigged first in 1929, and then again in 2000. As we’ve shown in our work, in both cases the period preceding the collapse was marked by distributional extremes: both in the late 1920s and in the 2000s, the top 10% of the U.S. population controlled nearly half the income. However, it is worth noting that the underlying inequalities today are probably greater than they were during the 1920s. To illustrate, by 2010, the national income share of capitalists (interest and profit), of after-tax profit, and of the net profits of the top 0.1% of all corporations (a proxy for dominant capital) were all at record highs, exceeding anything recorded since 1929, the first year for which full national income data are available.

In order to increase and sustain this type of differential accumulation-cum-power, dominant capital has had to inflict more and more threats, sabotage and anguish on the underlying population. This damage has taken numerous forms, one of the most striking of which is shown in Figure 2.

The solid line, plotted against the left scale, depicts the income share of the top 10% of the U.S. population. The dashed line, plotted against the right scale, measures the ratio between the adult “correctional population” and the labor force (the correctional population includes the number of adults in prison, in jail, on probation and on parole).

As we can see, since the 1940s this ratio has been tightly and positively correlated with the distributional power of the ruling class: the greater the power indicated by the income share of the top 10% of the population, the larger the dose of violence proxied by the correctional population. Presently, the number of “corrected” adults is equivalent to nearly 5% of the U.S. labor force. This is the largest proportion in the world, as well as in the history of the United States.

Although there are no hard and fast rules here, it is doubtful that this massive punishment can be increased much further without highly destabilizing consequences. And yet, the logic of differential accumulation dictates that redistribution and the accompanied increase in sabotage must continue. This clash between the imperatives of capital as power and the instability it engenders explains why leading capitalists have been struck by systemic fear. Peering into the future, they realize that the only way to further increase their distributional power is to apply an even greater dose of violence. Yet, given the high level of force already being exerted, and given that the exertion of even greater force may bring about heightened resistance, they are increasingly fearful of the backlash they are about to unleash. The closer they get to the asymptote, the bleaker the future they see.

6.

Piotr Dutkiewicz: What next for power, capital and the market?

Jonathan Nitzan: To answer this question, we need a new – and very different – research institute.

To re-search means to search again, and that is exactly what the current theoretical-ideological impasse calls for. As we have reiterated throughout this interview, the existing approaches to capitalism – liberal and Marxist – have run their course. They rely on the wrong assumptions; they use fictitious building blocks; they employ misleading categories, concepts and research methods; and most importantly, they often ask the wrong questions. They lead us to a dead end.

Capitalism is not a mode of production and consumption. It is a mode of power. And in order for us to transcend this mode of power, we first need to properly understand its structure, development and crises. In short, we need a cosmology of capitalist power.

Such a cosmology, though, cannot be concocted out of thin air. A new cosmology emerges not from the self-organization of Platonic ideas, but from the relentless empirical inquiries of flesh-and-blood researchers. The detailed empirical investigations of these researchers yield new evidence and novel regularities; the new evidence and regularities undermine and eventually shatter the old dogma; and with the old dogma having been debunked, the door is open for a new system of assumptions, concepts, questions and theories.

This is how modern science was born in the sixteenth century. It emerged not from re-idealizing religion or revamping moral theory, but from empirical research. It was the celestial observations of Copernicus, Tyco Brahe, Johannes Kepler and Galileo Galilei, the hands-on surgical procedures of Andreas Vesalius, the discovery of systemic circulation by William Harvey, the chemical experiments of Richard Boyle and the detailed analysis of magnetism by William Gilbert, among others, that helped undermine the old dogma. And it was this empirical research that eventually gave birth to a novel method of inquiry we now call science. “There is no empirical method without speculative concepts and systems,” says Albert Einstein, but also, “there is no speculative thinking whose concepts do not reveal, on closer investigation, the empirical methods from which they stem.”[3]

Piotr Dutkiewicz: Can you illustrate this theoretical-empirical duality in the study of political economy?

Jonathan Nitzan. Certainly. Take the Keynesian Revolution of the late 1930s. Although Keynes and his followers retained the Newtonian determinism of neoclassical economics (utility-maximizing agents, individual rationality, perfect competition, etc.), their framework nonetheless undermined basic tenets of bourgeois orthodoxy. It separated the macro sphere of government and state from the micro world of consumers and producers, it offered different ethics for private and public management, and it allowed – and indeed called for – stabilizing fiscal and monetary policies by governments.

However, even this limited bourgeois revolution would have been impossible, indeed inconceivable, without a prior empirical-statistical basis – in this case, the prior development of systematic national accounting. The first steps in that direction were taken at the end of the nineteenth century in Europe, the United States and other countries, and they culminated in the 1920 foundation of the U.S. National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) and the official publication of the country’s first national accounts in 1934. Without this emergent empirical picture of national aggregates, it is doubtful that Keynes could have imagined a distinct “macro” perspective, let alone a theory that related its underlying flows and stocks.

Piotr Dutkiewicz: What does that mean for radical students of society in general and for the study of the capitalist mode of power in particular?

Jonathan Nitzan. In order for us to develop – and negate – the cosmology of capitalist power, we too need an empirical infrastructure; and that infrastructure is yet to be created. The importance of such infrastructure for radical undertakings can be gleaned from the evolution of twentieth-century Marxism. When Lenin wrote his 1917 book Imperialism, the data on which he based his argument were meager and fractured. There were no organized statistics, no time series and no aggregate facts to speak of. Much of his evidence was drawn from works published twenty years earlier by the left-liberal political economist John Hobson. The situation was quite different half a century later. In 1966, when American Marxists Paul Baran and Paul Sweezy published their Monopoly Capital, systems of national accounts had already been implemented, primarily in the developed countries, and aggregate data analysis had become increasingly commonplace. This new infrastructure enabled Baran and Sweezy to enlist the help of Joseph D. Phillips, a statistical expert who subjected their thesis to systematic empirical examination. The result, published in the famous appendix to their book, was an empirical feat that Lenin could not even have fathomed. And yet, even Baran and Sweezy had to restrict their analysis to the United States, and particularly to its macro economy: national accounting was still far less developed in the rest of the world; organized statistics for corporations and financial intermediation were still in their infancy; and global databases were not yet on the radar screen. It was only in the 1980s, with the transnationalization of capital and the advent of cheap computing, that a global statistical picture, however imperfect, became a practical possibility.

These new data and the relative ease with which they can be accessed through the internet offer research opportunities that earlier critical thinkers could only dream of. However, I think we need to bear in mind that these databases have been conceived and developed to serve the capitalist mode of power, not to undermine it. They are geared toward the interests of accumulation, and, as such, they reflect the assumptions, categories, methods and theories of neoclassical economics – the ruling ideology of the accumulators. This fact serves to explain why Marxists have found it increasingly difficult to distance their empirical analyses from those of their class enemy. Having failed to develop their own statistical methods and corresponding data, they have gradually been forced to use those of the neoclassicists. And by using these methods and data, they ended up, often without noticing that they were doing so, validating the very approach they seek to reject.

We need to get rid of all this baggage. To be radical means to go to the root, to start from scratch. We need to develop new questions, new method, new categories, new data and, finally, an entirely new mode of accounting. We need to re-draw the capitalist map in a manner that will uncover and depict the logic and reality of capitalist power. We need to measure the aggregate and differential manifestations of this power in different regions, countries and sectors and at different levels of analysis. We need to identify the specific strengths and weaknesses of that power, so that we can know how to resist and overturn it. And to do all of that, we need to revolutionize the way we think, interrogate and investigate.

This kind of revolution demands an organizational Ctrl-Alt-Del. It requires a new, autonomous research institute – a non-academic scientific organization that will be independent of neoclassicism, Marxism and postism. The purpose of this research formation will be to lay the empirical-theoretical groundwork for a new cosmology of the capitalist mode of power, as well as a counter cosmology to help us creorder a humane alternative.

Endnotes

[1] Quoted in Amos Elon, Founder: A Portrait of the First Rothschild and His Time (New York: Penguin Books, 1996), p. 109.

[2] The first Gulf War (1990-91) was predicted in Robin Rowley, Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan, “The Armadollar-Petrodollar Coalition and the Middle East,” Working Paper 10/89, Department of Economics, McGill University, Montreal, 1989, Section 2.3. The second Gulf War (2002-) was predicted in Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan, “Putting the State In Its Place: US Foreign Policy and Differential Accumulation in Middle-East ‘Energy Conflicts,’” Review of International Political Economy, 1996, Vol. 3, No. 4, Section 8.

[3] Albert Einstein, Foreword to Galileo Galilei, Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems – Ptolemaic & Copernican, Translated by S. Drake. 2nd ed. (Berkeley and London: University of California Press, 1953 [originally published in 1632]), p. xxviii.