Ecological limits and hierarchical power

from Blair Fix, Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan

Nowadays, it is commonplace to claim that the economy overuses our limited material and energy resources (Figure 1) and that this overuse threatens both human society and the biosphere. Other than ant-science cranks, the only ones who seem to deny this claim are mainstream economists (Fullbrook 2019).

In our view, though, this conventional condemnation of the economy is somewhat misleading. As we see it, the root of our ecological problems lies not in the ‘economy’, but in the hierarchical power structure of capitalism.

- Hierarchy as a Means

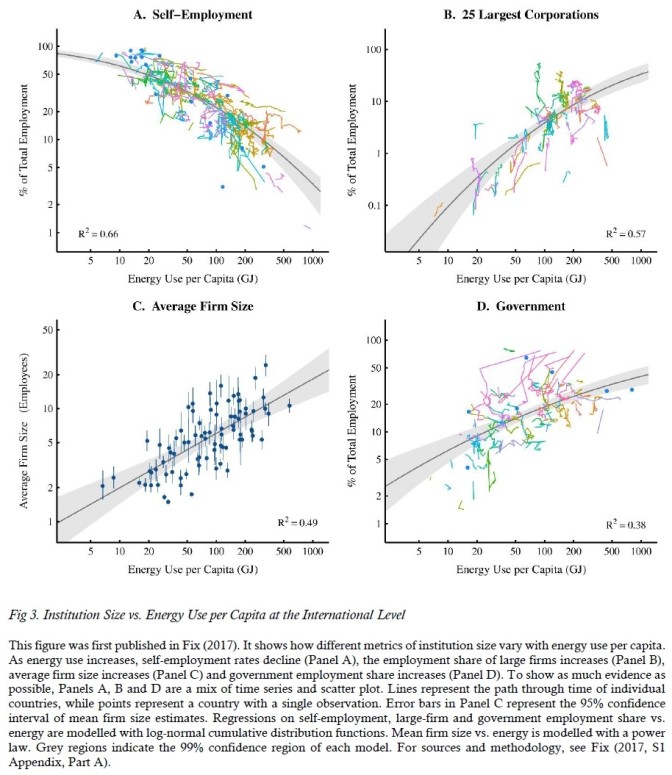

In his PLOS ONE article, ‘Energy and Institution Size’ (2017), Blair Fix shows that per capita energy capture (or energy use) is positively and often tightly correlated with organization size, both corporate and governmental: the larger and more hierarchical the organizations in a society, the greater that society’s capture of energy per person.

This positive correlation is evident in the U.S., where time-series data go back to the late nineteenth century (Figure 2).

And the same positive correlations – using time-series/cross-section data – are also evident internationally (Figure 3)

Fix’s explanation for this positive correlation emphasizes ‘economies of scale’ (Figure 4). Higher energy capture, he argues, demands increasingly complex coordination. Human beings, though, are limited in their natural ability to organize in larger groups. According to Robin Dunbar (1992), the size of the human neocortex makes it impossible to maintain stable personal connections with more than 150 people, give or take (Dunbar’s Number).

The historical solution to this coordination problem is hierarchy (Turchin and Gavrilets 2009). In a hierarchy, each person has a limited number of personal connections – one superior above and a few subordinates below. The modular nature of these connections makes it possible to combine them into huge vertical organizations of almost any size (think of a country like China).

From this viewpoint, hierarchical power is a means of harnessing more energy. Societies that wish to increase their standard of living can do so only by accepting more hierarchical power structures. Without such vertical structures, they would be unable to coordinate on a scale large enough to harness the energy they need.

- Hierarchy as a Goal

But there is a flip side to this argument. In their paper, ‘Growing through Sabotage: Energizing Hierarchical Power’ (2017), Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan argue that much of the energy harnessed by hierarchical societies does not go to wellbeing at all, but rather to building, fortifying and sustaining power hierarchies as such (Figure 5).

The starting point of this argument is that capitalism is best understood not as a mode of production and consumption, but as a mode of power (Nitzan and Bichler 2009). According to this view, the power of a capitalist or a group of capitalists is quantified by differential capitalization – namely, by the size of a group’s capitalization relative to the capitalization of other groups or entities (for example, the ratio of Amazon’s capitalization to Google’s; FAANG’s to the S&P 500’s; the top ten global integrated oil companies’ to Datastream’s world aggregate of all firms; the S&P 500’s to the U.S. population’s average, etc.).

From this perspective, capitalists are driven to augment their power for the sake of power – a quest that leads to a never-ending differential race to erect larger and larger hierarchical organizations, regardless of whether these organizations are more ‘effective’ capturers of energy.

Moreover, the build-up of hierarchical power elicits resistance from those who are subjected to this power, which in turn drives capitalists to build even more hierarchies in order to limit and contain that resistance.

For our purpose here, the key points of this flip argument are that (1) building and sustaining hierarchies requires plenty of energy; (2) the proportion of energy devoted to sustaining hierarchy tends to increase over time; and (3) a large and growing share of our energy use as a society has little or nothing to do with the wellbeing of the population. [1]

- It’s Not the Economy, It’s the Hierarchy

This thinking raises an interesting possibility. What if the recent exponential growth of energy capture (Figure 1) is caused not by ‘economic growth’, but by the growth of hierarchical structures? In this case, achieving sustainability would require dismantling the capitalist hierarchies that dominate us. [2]

Whether these hierarchies can be undone – and before it is too late – is of course a different question altogether.

Endnotes

[1] These claims should not be confused with David Graeber’s notion of ‘bullshit jobs’ (Graeber 2018). Whereas Graeber identifies the rise of meaninglessness and waste, Bichler and Nitzan emphasize the fortification and extension of differential power. On the difference between wasteful spending and investment in differential power, see Bichler and Nitzan (2017, Section 12.3)

[2] We are speculating here that the expansion of hierarchical power drives the growth of energy. Even if the causal direction is reversed (the need for more energy requires more hierarchy) or is circular (energy and hierarchy drive each other), the need to dismantle hierarchy still seems plausible. If the energy-hierarchy correlation remains positive, a world that uses less energy is likely to be less hierarchical.

References

Bichler, Shimshon, and Jonathan Nitzan. 2017. Growing through Sabotage: Energizing Hierarchical Power. Working Papers on Capital as Power (2017/02, July): 1-59.

Dunbar, R. I. M. 1992. Neocortext Size as a Constraint on Group Size in Primates. Journal of Human Evolution 22 (6, June): 469-493.

Fix, Blair. 2017. Energy and Institution Size. PLOS ONE 12 (2, February 8): 1-22 + appendices.

Fullbrook, Edward. 2019. Economics 101: Dog Barking, Overgrazing and Ecological Collapse. Real-World Economic Review (87, March): 33-35.

Graeber, David. 2018. Bullshit Jobs. First Simon & Schuster hardcover ed. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Nitzan, Jonathan, and Shimshon Bichler. 2009. Capital as Power. A Study of Order and Creorder. RIPE Series in Global Political Economy. New York and London: Routledge.

Turchin, Peter, and Sergey Gavrilets. 2009. Evolution of Complex Hierarchical Societies. Social Evolution & History 8 (2): 167-198.

1. The text links do not work but the reference links do work.

2. On the issue of hierarchies and management fads, I noticed that re-organizations in my bureaucracy were popular with managers. I think ordering re-organizations gave them something to do. Functionally, it acted as a reassertion and reminder of their power. Nothing says “I have power over you” better than ordering someone to do something useless. I guess it’s the same as ordering holes to be dug and filled in again. We need to remember that such hierarchical nonsense is not only the preserve of government departments. It’s just as powerful in corporate hierarchies. The graphs in the article bear this out.

3. Notwithstanding the costs of hierarchy, the full dismantling of hierarchy could lead to anarchy. When I think of anarchy I think of warlord-ism not peaceful co-existing communes. I tend to think that is where matters could lead in a breakdown situation. The salient issue perhaps is how to flatten hierarchical structures without removing them completely. A consideration of powers of ten illustrates that an organization of 10,000 only needs 4 hierarchy levels or maybe 5, if each person manages 10. Could it be that simple?

2. Your point here is similar to that of Graeber in his book “Bullshit Jobs”. The claim in “Growing Through Sabotage” is different. Hierarchies, we argue, are not there only to flatter those who control them. They are there to maintain and augment their power. In this sense, the cost of capitalist hierarchies should be viewed not as waste, but as an investment in capitalized power.

3. The flattening of hierarchies can occur either through the decline of the mode of power (which you refer to as anarchy), or through democratization. In terms of our “hierarchy-energy space”, or hes, the former is described by Trajectory D; the latter by Trajectory C. See: https://twitter.com/BichlerNitzan/status/1112347573740883968.

2. I agree on point two. The Graeber viewpoint can be the limited perspective of the worker. The worker feels frustration when arbitrarily ordered to do things which he/she sees are pointless from the functional viewpoint of getting the real work done.

3. I think a steep trajectory D would end in anarchy, at least until populations adjusted through collapse. Trajectory D is a crash landing. Trajectory C is the desirable trajectory, of course, and in a sense is a controlled emergency landing.

Sociocracy is an interesting variation on hierarchy in which information flows both down and up and, in my understanding, leadership is distributed through the organisation. See the book We the People:

https://www.sociocracy.info

Thanks for the column. It fits my growing perception that command hierarchy has been intrinsic to ‘civilisation’ (living in cities) from the beginning 6000 years ago. See two books called Against the Grain, one by James C. Scott on early states, the other by Richard Manning on how domestication serves the powerful and limits our lives. Oh and Daniel Quinn’s Beyond Civilization.

Professor R.D. Wolff’s call for Democracy in the Workplace or Democracy at Work is relevant here. I will leave people to search the net for those terms.

I think I erroneously switched the descriptions of the two trajectories. So let me try to get it right (see also this summary table: https://twitter.com/BichlerNitzan/status/1112348367676473344).

Trajectory C: Declining Mode of Power.

In this trajectory, overall energy capture per capita, livelihood energy per capita and the share of energy going to hierarchy are all falling. This trajectory is likely to be associated with MOP disintegration and societal decline.

Trajectory D: Democratizing Mode of Power.

Here livelihood energy per capital is rising, while the share of energy going to hierarchy is falling. With these given, we can further distinguish between two sub-trajectories: D1, in which overall energy per capita is rising (eventually unsustainable) and D2 in which overall energy per capita is falling (possibly sustainable).

From the point of view of a person who has both experienced employment where one is treated as an ignorant slave without the ability to think and other positions such as working farm manager and later sales rep. I THINK the above blog and posts deserve a lot more consideration in order to understand how people think and are motivated, and reflect te community and cultural groups they live and work in.Ted