Exciting news! Capital as Power — the seminal text written by Jonathan Nitzan and Shimshon Bichler — is now available for free as both an epub and online book. Full disclosure: the typesetter was yours truly.

What’s Capital as Power? And why did I make a free ebook version? Read on to find out.

You must unlearn what you have learned1

I don’t talk much on this blog about my personal journey. That’s mostly because I’m not interested in telling it. I find it annoying when scientists weave personal stories into the exposition of their ideas. In this regard, I’m probably odd. Scientists that tell good stories tend to win Pulitzer Prizes. So apparently many people (or at least literary critics) like their science in story form. With that in mind, here’s the story of why I typeset Capital as Power as an ebook.

The story starts about a decade ago. At the time, I was an amateur political economist looking for good ideas. I was interested in peak oil and climate change, but also in income inequality. I knew neoclassical economics was bullshit (I’d read Steve Keen’s Debunking Economics). But what about the other big canon of political economy — Marxism? I’d read Marx’s Capital and was impressed by his historical accounts. But his theory seemed tenuous. He simply assumed (without evidence) that labor created all value.

These problems, however, didn’t keep me up at night. My main job at the time was learning physics. (I was trying to become a physics teacher.) But that would eventually change. A few years later, I found myself in grad school studying political economy. It was then that I discovered Capital as Power.

My route of discovery is worth telling, because it highlights the importance of peer feedback. In the spring of 2012, I wrote a paper called The Thermodynamics of Neoliberalism. In it, I tried to connect trends in energy use to the emergence of neoliberal politics. In hindsight, there isn’t much in this paper worth keeping. The title is pretentious, and the ideas are vague. But that’s actually why the paper is important.

I sent the paper to biophysical economist Charlie Hall, hoping he’d give me feedback. And he did. In fact, he tore the paper to shreds. Importantly, he pointed out that I was using the phrase ‘capital accumulation’ constantly. But I’d never bothered to define ‘capital’.

At first, I was annoyed by Charlie’s feedback. But after a few days, I realized that he had a good point. I’d adopted a habit that’s rife in political economy — especially among leftists. I spoke ubiquitously about ‘capital accumulation’. But I had no idea what was being accumulated.

And so I turned to the internet. Into the search bar I put something like ‘critical theories of capital’. In the results a title caught my eye: Capital as Power. Interesting name, I thought. So I read the book. With that fateful click, my scientific journey was forever changed. The book upended almost everything I thought I knew about economics.

The thesis in Capital as Power is simple: economists don’t understand ‘capital’. Here’s the problem. In both neoclassical and Marxist theory, capital is supposed to have two sides. On the one side is money. On the other side is so-called ‘capital goods’. The two sides are suppose to be connected. In neoclassical economics, the value of capital goods is supposed to be proportional to their ability to create ‘utility’. In Marxist theory, the value of capital goods is supposed to be proportional to the embodied labor time.

If you read political economy, you’ll find that this capital duality is everywhere. Almost everyone accepts it, at least implicitly. But in Capital as Power, Nitzan and Bichler show that this duality is untenable. The reason is simple: there’s no way to connect the quantity of capital goods to financial capital. Why? Because the units of the conversion — utility in neoclassical theory and socially-necessary abstract labor time in Marxist theory — don’t exist!

To me, this realization was jaw dropping. But there was more. That’s because Capital as Power is really two books. The first half is a devastating takedown of existing theories of capital. This criticism alone would make the book standout. But the second half makes the book a classic. After tearing neoclassical and Marxist theory to shreds, Nitzan and Bichler build their own theory of capital. Capital as power.

Here’s their theory in a nutshell. Capital, they argue, isn’t a thing. It’s a ritual — the ritual of capitalization. Start with property rights. In capitalist societies, property owners are entitled to earn income from their property. They then take this income stream and capitalize it — meaning give it a present value. So ‘capital’ is the ritual conversion between an income stream and a stock of wealth.

The key, though, is what lies under this conversion. Property rights. For centuries, political economists have tried to connect the value of capital to what is owned. But Nitzan and Bichler think this is a mistake. The value of capital, they argue, stems from the act of ownership — the exclusionary act of power. So capital is a quantification of owners’ power. Capital is power.

What are the chances?

Reading Capital as Power blew my mind. But here’s the crazy thing. When I finished the book, I realized that one of the authors — Jonathan Nitzan — taught at York University. Not only was that in Toronto, where I lived. York University was where I was doing my masters degree. Nitzan’s office was literally steps from where I studied.

So in the fall of 2012, I took Jonathan’s course called Global Capital. I loved it for two reasons. First, the content was fascinating. Second, Jonathan’s research philosophy struck a chord. He was adamant that science had to be empirical. Yes, in physics there could be a separation of labor between theory and experiment. But in political economy, there was no such luxury. If you wanted to understand the world (as a political economist), you had to roll up your sleeves and find the evidence yourself.

So not only did Capital as Power shape how I view the world, studying with Jonathan Nitzan made me the researcher that I am.

A foray into publishing

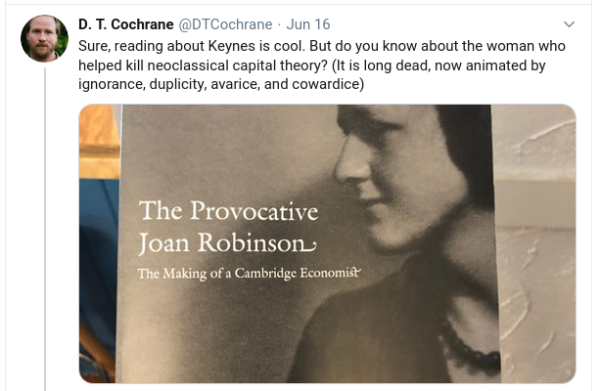

Fast forward to a few months ago. My foray into publishing began with a tweet from fellow economic heretic D.T. Cochrane:

In the ensuing Twitter thread, the Cambridge capital controversy came up. The Cambridge controversy was a debate in the 1950s and 1960s about the nature of capital. Economists Joan Robinson and Piero Sraffa (of Cambridge, UK) showed that the stock of capital goods couldn’t be measured objectively. This threw a wrench in the neoclassical theory of capital (defended by Paul Samuelson and Robert Solow of Cambridge, Massachusetts).

Back to Twitter. Evonomics publisher Steve Roth entered the thread. On the Cambridge controversy, Roth observed:

What’s the relationship between real capital and monetary wealth? Such a great question — one that I had struggled to answer. I responded:

That would have been the end of it, except later that day Steve asked:

Unfortunately, there wasn’t a free ebook version of Capital as Power. Some back story. When Nitzan and Bichler wrote the book, they negotiated (with Routledge) to have the PDF version become Creative Commons after a year. So in the spirit of open science, the PDF of Capital as Power has been free for a decade. But not so the epub version. It remained under the publisher’s paywall.

That’s where I come in. Capital as Power fundamentally changed how I see the world. I wanted other people to have the same experience. Added to this fact is that, for some time, I’ve wanted to learn how to make an ebook. So here was the chance to do two things at once: learn a new skill and make a great book freely available in a new format. And so over the last few months, I worked to convert Capital as Power into a free epub and html version. The results are now up at the Bichler & Nitzan Archives.

(Full disclosure: Jonathan Nitzan was generous enough to pay me for my time.)

The tools

I’m an ardent supporter of open source software. Regular readers will know that I use R for most of my empirical analysis. Well, it turns out that you can now use R for publishing. Software engineer Yihui Xie has created a package called bookdown that is a major leap forward in open source publishing.

Bookdown let’s you write in a simple markup language called Markdown. What’s important is that from one source document, bookdown lets you export multiple formats. You can create an online book, an epub and a PDF all in one go. The results out of the box are beautiful. But if you’re fussy (like me), everything is easy to tweak.

What this means is that authors essentially have no need of publishers. You can easily make electronic books that are as good (if not better) than what a publisher would create. This is especially important in academic publishing, where publishers charge exorbitant prices for pay-walled material. I firmly believe that all scientific knowledge should be open access. Bookdown makes this easy to accomplish.

Once you’ve created an ebook, you can host it for free on GitHub. That’s where I’ve hosted the html version of Capital as Power (below). And GitHub is where I plan to host future books when I write them.

[If you’re interested, the source code for the Capital as Power ebook lives here.]

Read Capital as Power

Back to Capital as Power. Some books make a splash when they’re published but are soon forgotten. Other books land with little fanfare, but become more important with time. Capital as Power is the second kind of book.

Although written eloquently, Capital as Power was never designed to be a bestseller. It’s far too thorough for that. In taking down existing theories of capital, Nitzan and Bichler leave no stone unturned. They mount a 150-page assault on ideas that most political economists hold dear. This devastating critique is absolutely necessary, but it comes with a cost. It means that readers who are primarly interested in Nitzan and Bichler’s own ideas about capital have to wait until the middle of the book.

With that in mind, here’s my recommendation. If you’re interested in what’s wrong with neoclassical and Marxist theory, read Capital as Power from the beginning. But if you’re already skeptical of these theories, and just want Nitzan and Bichler’s new approach, start with Chapter 9, Capitalization: a brief anthropology. It’s from here onward that Nitzan and Bichler lay out the ritual of capitalization and build their theory of capital as power.

Today, as wages stagnate and stock markets sore, it’s more important than ever to understand the nature of capital. On that front, Capital as Power is destined to become a classic. It questions the foundations of political economy, and dares to take the field in a new direction. It surely belongs with Marx’s Capital in its breathtaking scope. The difference, however, is that Nitzan and Bichler are scientists to the core — adamant that they neither need nor want an army of admirers. Unlike Marx, Nitzan and Bichler don’t connect their research to any particular political goal. In these hyper-partisan times, that makes their theory less palatable . But it does one big thing. It keeps things scientific.

Capital as Power contains no easy solutions for how to make the world a better place. Instead, it lays out a framework for how to understand capitalism. Like everything in science, that framework is unfinished. So read Capital as Power and have your worldview turned upside down. Then get on with the project of building a better theory of capitalism.

Support this blog

Economics from the Top Down is where I share my ideas for how to create a better economics. If you liked this post, consider becoming a patron. You’ll help me continue my research, and continue to share it with readers like you.

Stay updated

Sign up to get email updates from this blog.

Fascinating. I still have to find the time/energy/commitment to read that book.

I’m not an economist, but an interested citizen. Do you think there will ever be a condensed version aimed at general audiences?

It’s infuriating that so much energy in economics is devoted, essentially, to supporting the status quo with mysticism in the form of mathematics. Religion has been distilled into ideology, and theology into economics.

But this seems to be how social power works. It’s all based on beliefs, which are, in turn, based on nothing besides habit and inertia. Power seems to aggregate—to congeal—in the same way matter does, in stars and galaxies. Some small random perturbations lead to imbalances, which lead to large concentrations, and vast areas of near vacuum.

It is the power law and winner take all effect.

But in society, people are conscious of—and displeased by—this “natural” phenomenon, and want to counteract it. So those who have power—solely by accident of history—use that power to reinforce it, both materially and culturally. Whatever the reigning ideology or mythology, they use their influence to corrupt those who are corruptible, making devil’s bargains, and using them to spin stories that justify the way things are.

What kills me is that it’s so obvious, and yet so many people are incentivized to be blind to it. We are, as pragmatic social beings, motivated to take things as they are—or appear to be—and make choices that benefit us. The fact that so much of the functional features of society are interdependent upon social mythology also makes it seem very risky to attack the latter without fear of harming the former.

Maybe one day we will be more enlightened. All we can do is try.

LikeLike

One more thing: is there still no agreed upon fundamental unit of economics? Or productivity? Or something to start from? Besides “money”?

What is the atom that determines the organization of human activity? Is it not the person?

Or is the entire field in fact purely imaginary? Is it possible that there is no physical correlation to our ideas of work, production, and value? If that is the case, what is the use of applying math to questions of economics, or more fundamentally, questions of human welfare?

Or is the unit of economy the same as in any dynamic material environment: energy? (Or “exergy”, as I’ve heard argued elsewhere? Or work?) Is it always and only energy or some variant? But then how do we evaluate whether energy is used well or poorly? That is, how do we make decisions about how to divert streams of energy to one activity or another? How do we evaluate choices as better or worse?

Utilitarianism doesn’t seem feasible, but what other system is there?

What I hate about economic theories of rational actors is not so much the impossibility of having perfect information about the outcome of economic decisions, but the instability of how we evaluate those outcomes. We change our minds, from day to day, and from moment to moment, based on changes in the environment and in our emotional states, which are in turn affected by the environment, including our bodies. When we are hungry, we want to buy food, but when we are sated, we want other things. How can we ever formulate a consistent theory of value or utility when our needs, and perceptions of our needs, are so fluid?

It seems like, as a society, we need to do some first principles thinking. Unfortunately, any minority of people with power have a different agenda than any political community “in toto”: they want to shore up and increase their power. Everything else is a smoke screen for that.

LikeLike

About the unit in economics.

All (or nearly all) economists agree that what defines the discipline is its focus on prices. So in affect, prices are the basic unit. But as you’re aware, that doesn’t get you anywhere. We want to explain prices. On this front, economics has basically gotten nowhere.

In some ways, prices themselves are the problem. As Nitzan and Bichler observe, prices aren’t an objective property of commodities. They’re part of what Aristotle called the nomos — the social structure of society. Prices are a quantitative nomos — a unit of account used to organize human activity. The mistake, for centuries, has been to think that something equally simple and equally quantitative lies under prices. But that’s an illusion. Prices themselves may be beautifully simple, but their existence is a messy outcome of social dynamics — sometimes small scale but often involving large-scale power. This means that there is no simple way to understand prices like is proposed in neoclassical economics and by Marx.

If we wanted to be really meta-critcal, we can say that economics is itself an artifact of the modern nomos. It elevates prices to a mystical level — a ‘pure’ outcome of utility maximization. So economics negates the very nomos that it exists to proliferate.

LikeLike

I never before understood this bizarre fact. How can a price be fundamental? It’s not invariant. It’s not even an independent value.

The fact that economists have so much power in the world is not only ludicrous, it’s terrifying.

How is it that every real scientist is not up in arms about the influence of economics? It’s madness.

Is it because economics is ultimately political? And sane people avoid politics? Politics has us all in its trap. And economists help keep us there. It’s a travesty. It’s inhumane. It’s criminal. What a world!

LikeLike

It is terrifying. But it is consistent with the history of ideologies. The powers that be always use ideas to legitimize their rule. Historically, these were mostly religious. But with the enlightenment, science became more important than religion. So the ideology of the day used the appearance of science (mathematics, postulates, etc) to appear legitimate. This was true from the start of economics. That so many people took the ideological claims as ‘science’ is a testament to how well this ploy worked.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’d change the wording somewhat. Prices are secondary. Monetary units of account are primary. They’re the key conceptual technology that eventually emerged (following the invention of abstract numbers themselves) out of the earliest one-to-one token-counting systems that prevailed from ca 8,000 to about 3,000 BCE.

If “price” means dollars or obols per unit, prices can’t even conceptually exist without that prior conceptual invention.

The emergence was complicated and fitful, beginning with (very early) physical commodity units, which started to be used as measures of different commodities. Eventually pure monetary units (often taking the names of commodity units) emerged and were used to designate numeric value for many or all goods.

Monetary units of account address the very problem and question we’re struggling with here: how do you designate the values of heterogenous goods, numerically? They’re what allow us to even create something we call a price list, or make a list of mixed goods and their values, with a sum at the bottom — what we do today on a brokerage statement or the asset side of a balance sheet.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good point.

LikeLike

Thank you Blair for the superb rendering of the ePUB and HTML, for telling readers about your own journey, and for recommending “Capital as Power.” Much obliged.

LikeLike

Steve,

It’s also possible to think of prices and money as two sides of the same thing. The underlying purpose of having a uniform unit of account is to universally quantify qualitatively different things by assigning them a money price. We wrote about this aspect in “Growing Through Sabotage” http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/639/, p. 42:

In early civilizations, the quantification of qualities was often associated with the imposition of power – including the ranking of deities, the measuring of wealth, the parcelling of land, the pricing of violence and the costing of protection, among other inflictions. One of the first written records of such quantification comes from a broken Sumerian clay tablet, written some four millennia ago. The tablet lists various offenses, assigning to each of them a specific pecuniary penalty:

“If a man has cut off with an . . . –instrument the foot of another man whose . . . ., he shall pay 10 shekels of silver. If a man has severed with a weapon the bones of another man whose . . . ., he shall pay 1 mina of silver. If a man has cut off with a geshpu-instrument, the nose of another man, he shall pay 2/3 of a mina of silver.” (Kramer 1963: 84-85; missing parts in the original)

LikeLike