Working Papers on Capital as Power, No. 2024/01, August 2024

You can read, quote, reference and link this working paper, but you cannot reproduce or post it in any form unless permitted in writing by the authors.

The Road to Gaza

Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan [1]

Jerusalem and Montreal

August 2024

Abstract

The war that started in 2023 between Hamas and Israel is driven by various long-lasting processes, but it also brings to the fore a new cause that hitherto seemed marginal: the armed militias of the Rabbinate and Islamic churches. The Rabbinate militias, embodied in Jewish settler organizations, have taken over not only Palestinian lands, but, gradually, also Israeli society. The Islamic militias, represented by Hamas and the Islamic Jihad, rose to prominence after the traditional resistance groups of the Palestinians – primarily the PLO and the PFLP and, by extension, also the Palestinian Authority – weakened and proved unable to reverse, let alone stop, the Israeli occupation.

The rise of these militias, though, is hardly unique to Israel/Palestine, or even the Middle East. It is part of a broader, global process, in which ‘private’ military organizations, financed by states, church-related NGOs and/or organized crime, fight for and against states as well as each other. The ascent of such groups is closely related to the decline of the nation-state and its popular armies, a model that developed in the wake of the French Revolution but no longer resonates with the increasingly globalized nature of capital accumulation.

Our previous studies of Middle East wars emphasized the ‘state of capital’ – our notion that the capitalist mode of power fuses state and capital into a single logic in which dominant capital groups are driven by the power quest for differential accumulation. We showed that, in the Middle East, this logic was imposed by a Weapondollar-Petrodollar Coalition of large oil and armament corporations, OPEC, financial institutions and construction firms, whose differential incomes and profits were tightly correlated with – and helped predict – the cyclical eruption of ‘energy conflicts’.

But this mode of power comprises not two elements, but three. In addition to state and capital, it also includes the supreme-God churches, and in this paper we outline the role of these churches and their militias in capitalism generally and in Middle East wars specifically.

1. The Militias

The Hamas-Israel war of 2023-24 has elicited different and often overlapping explanations. These explanations tend to emphasize long-lasting processes, including, among others, the struggle between the Zionist and Palestinian national movements, the many conflicts between Israel and Arab/Muslim states, the rift between western and eastern cultures and the contentions between the declining superpowers (the United States and Russia) and their rising contenders (like China, Iran and Turkey). But the war also brings to the fore a new factor, one that hereto seemed rather marginal and drew limited attention: the rising militias of the Rabbinate and Muslim churches.

The Rabbinate militias, embodied in Jewish settler organizations, have been operating for over half a century under the auspices of and with heavy financing from all Israeli governments (as well as from various neoliberal oligarchs and NGOs, local and foreign). These militias have managed to gradually capture Israeli society by the throat. Following the war of 1967, they have taken over more and more occupied Palestinian lands and, from the 2000s onward, seized key political parties, assumed control over large chunks of the media, penetrated and altered the education system, redefined the socio-political discourse and become a mainstay of the country’s civil service, security apparatuses and military. Looking forward, they plan to turn Israel – by force, if necessary – into a neoliberal-Rabbinate autocracy.

The mirror side of this process is the ascent of Islamic militias. The inability of the Palestinians to arrest, let alone reverse, the long Israeli occupation has caused their traditional resistance movements – mainly the PLO and the PFLP – to wither and the Palestinian Authority to weaken and grow more corrupt. The resulting void has been filled by armed Islamic militias – the Sunni Hamas and the Shiite Islamic Jihad. The former has been financed mainly by Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states, whereas the latter operates largely under the Iranian umbrella of the Ayatollahs.

The rise of these militias, though, is not a purely local phenomenon. It is part of a global process in which ‘private’ armies, backed and financed by states, religious NGOs and/or criminal organizations, fight for and against states as well as each other. The main cause of this broader process is the gradual decline of the nation-state, whose structure and limited reach no longer resonate with the increasingly globalized capitalist mode of power. Instead of representative democracies sanctioned by individual citizens, global capitalism now calls for oligarchic states legitimized by ‘big leaders’, corporate alliances and racist ideologies. And as this structural shift gains momentum, private forces and stand-alone militias gradually supplant the traditional ‘national army’ that grew out of the French Revolution. [2]

Our previous studies of Middle East wars emphasized the ‘state of capital’ – our notion that the capitalist mode of power fuses state and capital into a single logic in which dominant capital groups are driven by the power quest for differential accumulation. We showed that, in the Middle East, this logic was imposed by a Weapondollar-Petrodollar Coalition of large oil and armament corporations, OPEC, financial institutions and construction firms, whose differential incomes and profits were tightly correlated with – and helped predict – the cyclical eruption of ‘energy conflicts’ (Bichler and Nitzan 1996, 2015, 2018, 2023; Nitzan and Bichler 1995, 2009).

But then, this mode of power comprises not two elements, but three. In addition to state and capital, it also includes the supreme-God churches, and, in this paper, we outline their role in capitalism generally and in Middle East wars specifically. (We refer to the ‘supreme-God churches’ rather than to the ‘monotheistic churches’, mostly because our focus is not the belief of their followers but the hierarchical structures that impose these beliefs. As we explain later in the paper, all supreme-God churches are characterized, among other features, by their god’s insistence on and fight for exclusivity, hence the attribute ‘supreme’.)

2. The Supreme-God Churches

All three supreme-God churches started in the Near East, and not for naught: at the beginning of the fourth millennium BCE, dwellers of Mesopotamia and Egypt had the dubious honour of becoming the world’s first subjects of hierarchical, imperial states; the coercive nature of these states had to be legitimized and sanctified; and the role of doing so was assumed by hierarchical churches. [3]

As palatial rankings solidified, so did the pantheon of gods. Violence within and military conquests between states were accompanied by mergers and acquisitions among their deities. Consolidating hierarchies gave rise to supreme gods, thirsty for blood and eager for war. The gods climbed to the skies, severed their direct relations with their worshippers, and grew evermore mysterious and difficult to understand. A hierarchy of intermediaries – read, an organized church – was now responsible for representing and interpreting them. [4]

In the beginning of the first millennium BCE, temporary imperial weakness tempted peripheral rulers to imitate the king-gods of the centre. One of these emulators was a runaway convict named David, whose gang extorted local Philistine villagers and occasionally acted as mercenaries for local rulers. His first claim to ‘big man’ fame was appropriating the wife of a wealthy herder who refused to pay him protection. Later, he employed trickery and hired assassins to eliminate his opponents and install himself as king. To legitimize his rule, he forcefully took the daughter of a former king from her loving husband, having first annihilated her family. His most glorious moment was a blitzkrieg takeover of the autonomous city of Jerusalem, replacing its local forces with a Praetorian Guard of foreign mercenaries, declaring it his holly capital and announcing himself as an eternal, supreme king. Most importantly for our story, once in power, he cut a deal with the city temple to sanctify his dynasty in return for the clergy’s exclusive control over its local followers. Incidentally, the temple housed a particularly demanding god named Jehovah, who insisted on expelling all competing deities, so that his own priests could reign supreme over their subjects, the ‘children of Israel’. [5]

And as it turns out, this subjugation model proved remarkably successful – so much so, that in the early 21st century, many Jews (as well as Christians and Muslims) insist that a reincarnated version of that old Jerusalemite king will reappear as their ‘Messiah’, ‘Lord’, or ‘Mahdi’ (having previously slain their heretical enemies in bloody apocalyptic battles). [6]

In due course, Jehovah’s template developed into three supreme-God churches: the Rabbinate, Christian and Muslim. After consolidating in the first millennium AD, these churches adapted to the Byzantine, European and Ottoman empires; they then transformed to fit the new empires of 20th-century capitalism; and, finally, they adjusted to the 21st-century model of global accumulation.

The supreme god of each church is marketed under a different brand, but underneath the distinct logos lurk the same blood-lusting, imperial ambitions and similar modus operandi.

The first maxim of all three supreme-God churches is exclusivity: they all insist on a divine franchise, backed by threat, force and violence, to singlehandedly hold and control their subjects. Each church manifests this demand differently. The Muslim clergy, having been integral to Muslim rule and empire from the very start, did not have to jostle and struggle to control its subjects. But when an external calamity ensues or opportunity arises, it quickly bends its own divine rules to acquire and merge additional subjects.

An example of such calamity-turned-opportunity is the case of Genghis Khan and his heirs, who, during the 13th century, inflicted the greatest holocaust on Muslims, with some 40 million subjects butchered and large chunks of their empire left in ruins. For this murderous record, Muslims considered Khan ‘ملعون’ (mal’un), or ‘cursed’. They called him ‘God’s scourge’. But the calamity also had a clear upside: the victorious Mongol empire boasted a huge swath of potential converts to be taken over and merged into the Islamic church. And so, by the 14th century, Genghis Khan was honourably added to the Muslim pantheon, sanctified at the very top, second only to Muhammad. Once God’s scourge, he was now made a ‘Hanif’, or monotheist, a generic true believer with direct access to the one-and-only Allah (Biran 2007).

Unlike its Islamic counterpart, the Christian church began as a small, prosecuted community offering solidarity with and solace to people at the lowest social echelons of the Roman empires. But in 312, there was a game change. Jesus accepted protection from Constantine the Great in return for securing the latter’s victory over his pagan Roman enemy and false gods, and Christianity suddenly found itself an imperial church. Rising to the occasion, its theologists promptly rewrote its holy history. Constantine was turned into God’s emissary, entrusted with guiding the church’s laity to salvation. True, there were still a few small details to iron out – primarily, which church faction was best suited for the holy task – but with enough Christian grace and the emperor’s mighty sword, the Holy Trinity got the job to the exclusion of its phony competitors – the Arians, Donatists, Gnostics, Monophysites, Nestorians and other imposters.

The Rabbinate church, too, was off to a feeble start. During the second millennium, it lacked a permanent statist stronghold and depended entirely on tentative royal franchises issued by kings, princes and khalifs. Given that the permits could always be (and often were) revoked at whim, the Rabbis stuck to the prudent maxim of ‘ignorance is strength’: they kept their subjects uneducated and isolated from the broader environment, so that they could be easier to rule. Until the 18th century – and in much of Western Europe, until the mid-19th century – most Jews were confined to tightly controlled cultural and professional communities from which excommunication often spelled death. Only under exceptional circumstances – like those of the unmarried, high-tech-lens-polishing philosopher Baruch Spinosa – could Jews live outside those enclaves, safe from the Rabbis’ reach.

The second feature of all three churches is their demand for submission. Given their relations with and dependency on the prevailing mode of power, they all insist that their subjects obey the prevailing hierarchies of state, church, property and patriarchy. They also command them – with ample threats, both immediate and for the afterlife– to constantly reproduce, so that the fresh supply of god’s servants and the rulers’ slaves never dries out. [7]

A third common feature is branding. This practice is a common show of force in many modes of power. American settlers branded their Black slaves as did the Nazis their concentration-camp inmates; Manchu kings made their male subjects shave their heads and grow a braid; Chinese families footbound their young girls so they could fetch a high price in the upscale marriage market; etc. The Rabbinate and Muslim churches brand their male subjects by chopping off part of their penis. [8]

A fourth feature is misogyny. All three supreme-God churches systematically humiliate, oppress and subjugate women to their ruling hierarchy. [9] The Muslim church tops this treatment by allowing, if not encouraging, female genital mutilation and by turning a blind eye to family ‘honour killing’, among other bonuses. [10] In Eurocentric post-colonial lingo, we could say that the aim of this systemic torture and degradation is to ensure women remain the family property of men.

The fifth feature is xenophobia. Their insistence on exclusivity and knack for bedeviling competitors and ‘false gods’ make all three churches hostile to anything and everything foreign. All of them encourage, if not command, the killing of ‘infidels’, especially ‘atheists’. [11] And all of them – particularly the Muslim and Rabbinate churches – condone the enslavement of war prisoners and turning women captives into sex slaves (Tabari 1997: 34-40). During the so-called Muslim Golden Age of the 14-16th centuries, there was a prosperous Mediterranean trade in slaves kidnapped across Europe (Bono 2010; Davis 2001).

The sixth and final item on the list is doublethink – or ‘Taqiyaa’ (تقیة), as it is known in the Middle East. All three churches represent the ultimate truth, but they also possess a rich arsenal of masks, deceit and trickery that they use against powerful friends and foes alike. Depending on the circumstances, this arsenal of duplicity allows them to show off, either as zealous, uncompromising warriors – or as moderate, tolerant peacemakers. And they have deployed deception for so long and with such dexterity, that it has become second nature.

3. The Supreme-God Churches and the Capitalist Mode of Power

The 14th century presented a significant change. It brought, initially in Europe, a new mode of power which we now call capitalism, and this mode of power no longer resonated with the old churches. The new god of this mode of power – capital – represented a totally novel conception of power: anonymous, universal and commodified. It could be owned by anyone, travel anywhere and be traded by everybody. Moreover, it came with a new political framework – the nation-state – which was, in turn, largely shaped by capital for its own ends (on that later point, see Hobsbawm 1990). The interests, structures and flexible modus operandi of the nation-state fitted capital accumulation much better than those of the rigid church-bound kingdoms and sultanates.

Capitalism served to dismantle communities, particularly in the countryside, turning their interlinked people and families into stand-alone, easy-to-control urban atoms. Following the French Revolution, the prosecution of priests, the dismantling of church schools and the rise of primary state education had together helped boost patriotism, create large armies of citizens-conscripts and, most importantly, standardize the labour force for what, back then, was the beating heart of accumulation: the capitalist factory.

As the new state of capital developed, its rulers needed more and more skilled workers to conjure up new technologies, operate sophisticated equipment and bureaucracies and provide public services, so education had to be upgraded beyond the ‘elementary’ schooling of the French Revolution. Big capitalist owners and their governments gradually appropriated, reshaped and centralized the autonomous impulse of creative research that flourished, however sporadically, in the rising capitalist countries. They remolded it into an organized cult of mechanical rationalism, complete with new saints of enlightenment and knowledge, a brand-new method called science and new mental workers known as scientists. The logic of this new power cult was aptly summarized in 1933, by the logo of the World’s Fair in Chicago: ‘Science explores: Technology executes: Man conforms’ (Mumford 1970: 213).

Until the 19th century, the old churches continued to participate and legitimize imperial expeditions. This was particularly true of the Catholic church, whose exploits in South and Central (‘Latin’) America – including the mass murder of heretics and the conversion of millions to Christianity – have become legendary (Delumeau 1977: 85).

But gradually, the old churches were pushed out by the new. Scientific rationality substituted for old church scriptures. The enemies were no longer religious heretics, but people of inferior races – whether biologically, culturally or developmentally. Patriotism substituted for – or better still, merged with – religious conviction. Imperial loot, previously the gift of God, was now destined for and justified by scientific inquiry, technological development and economic growth.

And so, the supreme-God churches lost ground. Their abyss was the postwar era. The victorious Soviet Union helped spread the Leninist church worldwide, especially to China and the peripheral world. Ideologies of modernization, industrialization, urbanization and education, both liberal and communist, gained momentum. And finally – and damningly – the old churches were now seen as accomplices to the oppressive regimes of the dreaded past. To make matters even worse, the core capitalist countries flourished. The welfare-warfare regime of ‘military Keynesianism’ boosted government spending and social services, progressive taxation helped reduce income inequality and workers’ purchasing power soared. The cult of enlightenment and rationality gained momentum and the number of old-church followers dwindled. [12]

Notably, though, most of the world’s subjects, especially in poorer peripheral countries, continue to believe in a supreme god and dread its churchly representatives (Anonymous 2015). In the U.S., only 3% of the population considers itself purely atheist, (as distinguished from agnostic; Pew Research Center 2015). The global proportion of atheists is probably less than 5%, with most living in the richer, more educated countries.

But by the early 1970s, the Cold War model of military Keynesianism started to wither. The peripheral world started to contest the postwar international arrangements, while America’s defeat in Vietnam marked the beginning of the end of U.S. global supremacy. Economic growth slowed, inflation soared and unemployment seemed chronic. The state of capital, in the United States and elsewhere, entered a legitimation crisis, forcing its rulers to earmark more and more resources for oppressing/placating the boiling masses and manipulating their disobedient consciousness. It was time for a new, neo-liberal order.

The shift to this new order was front-windowed by Margaret Thacher and Ronald Reagan, but its underlying ideological blueprint was provided by the monetarist doctrine of Milton Friedman and the Chicago Boys. Catering to and heavily financed by dominant capital, this doctrine quickly became (and remains) the mainstay of economic theory and government policy the world over. It helped deregulate business activity (or rather, allowed dominant capital to regulate itself), reduce corporate and top personal-income tax rates, cut social services and budget deficits and commence a long process of pork-barrel privatization of state assets at bargain prices. The result, unsurprisingly, has been rising income and wealth inequalities, soaring corporate concentration, heightened business sabotage and increasingly aggressive xenophobic politics.

The French Revolution’s model of the liberal nation-state is now passe. In its stead, we witness the emergence of a new, oligarchic state of capital, decorated with ‘big leaders’ and stirred by the large owners and hierarchical bureaucracies of dominant capital. Liberal ideals of ‘progress’, ‘rationality’ and ‘equality’, irrelevant to this new reality, are giving way to an alternative lingo of ‘identity’, ‘race’ and ‘violence’, combined with – as we shall see below – the resurging rituals of the old supreme-God churches.

In the global periphery, where the nation-state has rarely developed fully, the disintegration flares up in multiple conflicts between regions, tribes, ethnic and church militias and criminal gangs. This process is prevalent across much of Africa, as well as in many parts of South America, Asia and the Middle East. Russian-supported militias – like the Wagner Group and Chechen forces – operate in Ukraine, Syria and Africa. The United States and its allies have been using corporate mercenaries in Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria. Wahhabi militias police the Saudi population, ISIS operates in Iraq and Syria, while the Taliban rules Afghanistan. The U.S. supports Kurdish militias in and around Kurdistan, the Houthis rule much of Yemen, the Iranian-backed Islamic Jihad and Hezbollah operate in Palestine, Lebanon and Syria, while various Islamic groups control parts of Nigeria, Libya, Sudan and Somalia, among other countries. Organized crime gangs, engaged mostly in raw materials and drugs, are prevalent in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Libya, Mexico, Colombia and Southeast Asia, often with global tentacles.

In the developed capitalist countries, the ritual of rational progress has declined, while the scientific-technological process has been appropriated and privatized, almost completely, by dominant capital. The ‘postist’ church has won over the shrinking middle strata. Having devoured the remnants of free scientific thinking and autonomous philosophy, it sanctifies racism (identity politics), political corruption (read correctness) and the appropriation by big accumulators of education, information and open dialogue (it’s all about power, anyway).

But postism cannot be easily imposed on the poorer, less educated parts of the underlying population, and it is here that the revival of the supreme-God churches comes in handy.

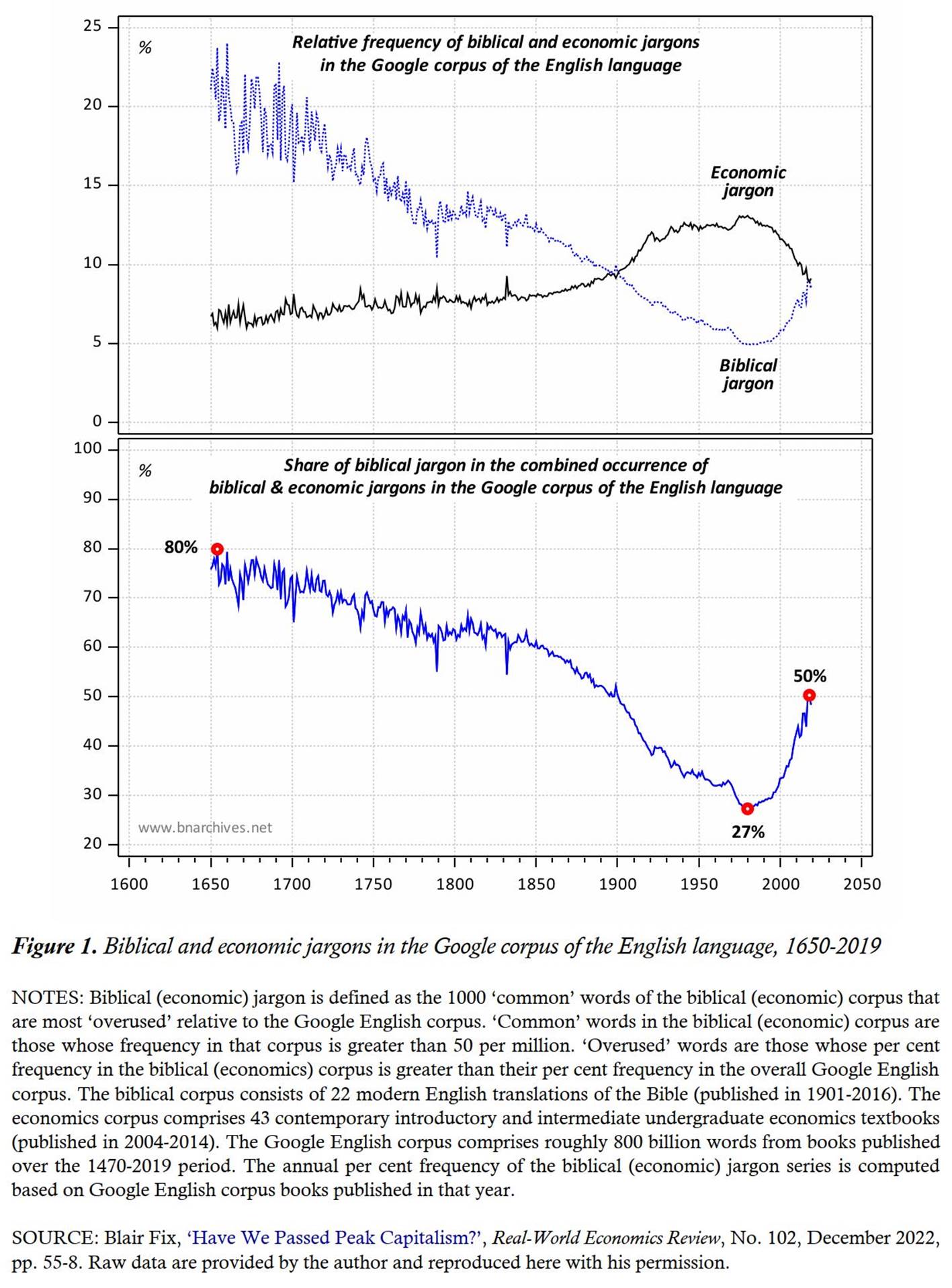

Figure 1 outlines this revival. The chart traces the historical evolution of two opposing rituals: the biblical ritual of the supreme-God churches, which promotes passive obedience and deference to prevailing hierarchies; and the rational ritual of economics, which represents the autonomous quest to understand and alter reality.

The data in the figure are from Blair Fix’s study of shifting ideologies in the capitalist epoch (2022). To conduct his research, Fix constructed two distinct jargons of 1000 words each – one based on modern English translations of the bible, the other on contemporary introductory and intermediate economics textbooks (for more details, see the notes and sources underneath the figure). Using these two jargons – whose contents are largely mutually exclusive – he then measured the relative frequency of each in the Google book corpus of the English language and assessed their historical development.

Figure 1 shows his data from 1650 to the present: the top panel plots the per cent frequency of each jargon in the Google corpus, whereas the bottom panel measures the per cent share of the biblical jargon in the combined occurrence of both jargons in the Google corpus.

The data portray a clear historical U-turn. In the middle of the 17th century, when capitalism and liberal enlightenment were taking their first steps, the submissive jargon of the church dominated: in 1654, it accounted for a full 80% of all biblical and economic words in the Google corpus (bottom panel). With the advent of capitalist modernity, however, the relative prevalence of church jargon dropped – from roughly one-fifth of all words published in English books during the second half of the 17th century, to a mere 5% in 1980 (top panel). The economic jargon, emphasizing autonomy and rationality, moved in the opposite direction, with its Google corpus frequency rising from 7% to 13% over the same period. And as the two opposite movements continued, the relative significance of the biblical jargon in the combined pool of biblical and economic words in the Goole corpus plummeted, reaching a low of 27% in 1980 (bottom panel).

But 1980 marked an inflection point, at which the two trajectories flipped direction: the rational economic jargon collapsed, while the submissive church jargon resurged. By 2018, the relative significance of the biblical jargon in the combined pool of biblical and economic words in the Goole corpus was back to 50%.

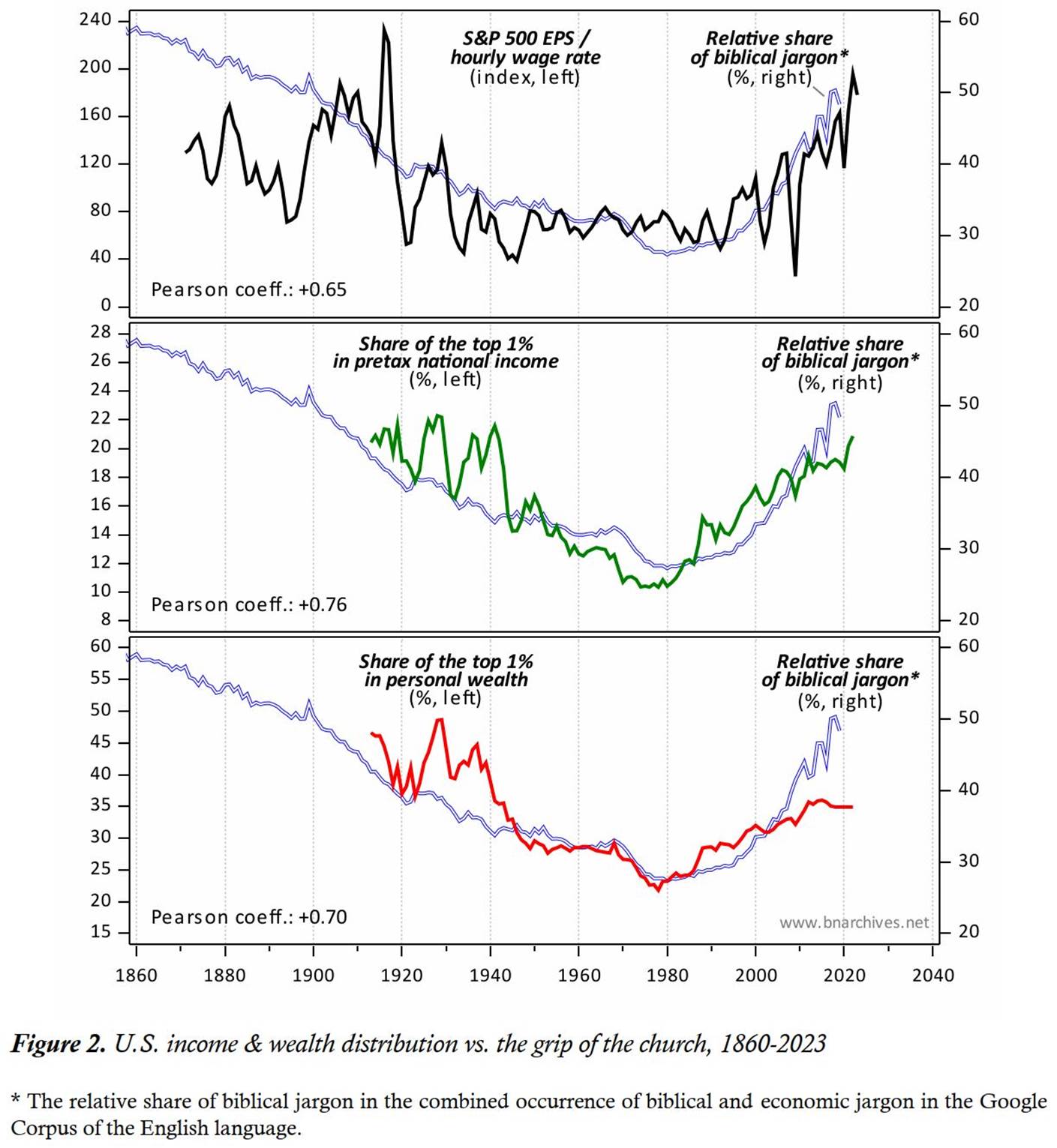

The key reason for this dramatic inflection, we argue, is that the rational-economic language of the monetarist church and the identity discourse of its postist counterpart have become insufficient to offset the rising capitalized power and strategic sabotage associated with soaring income and wealth inequalities. And it is here that the submissive biblical jargon of the supreme-God churches was called in to the rescue. The long-term contours of this process are outlined in Figure 2.

The chart associates the relative share of the biblical jargon in the combined occurrence of biblical and economic words in the Google corpus (double blue series, taken from the bottom panel of Figure 1) with three different measures of U.S. income and wealth inequality. The first measure, shown in the top panel, is the ratio between the S&P 500 earnings per share (EPS) and the average hourly wage rate. This measure, expressed as an index, compares the income of a typical capitalist owner with that of a typical subject in the underlying population. The second and third measures, shown in the middle and bottom panels, respectively, focus more narrowly on dominant capital and its power belt: the second measure shows the pretax national income of the top 1%, while the third depicts the share of this group in personal wealth.

The high Pearson correlation coefficients between these three distributional measures and the relative share of the biblical jargon leave little to the imagination: +0.65 for the EPS/wage rate, +0.76 for the pretax national income share of the top 1% and +0.70 for the personal wealth share of the top 1%. Given that our analysis covers both the fall and rise in the data’s V-shaped pattern, these results, repeating across all three measures, are hard to dismiss as a mere historical fluke.

Whereas the religious attitudes of the underlying population may have changed little since the early 1980s, the focus of those who underwrite the ruling class discourse clearly has. It shifted, decisively, away from the rational jargon of economics and toward the submissive jargon of the supreme-God churches, and it has done so exactly when dominant capital began to erect its new, oligarchic state of capital to boost its differential-accumulation-as-power. The road to a 21st-century cycle of church-sponsored violence and war was now wide open.

4. The Road to Gaza

The first region where the Muslim and Rabbinate churches systematically impacted the accumulation of capital is the Middle East.

After the First World War, the region was parcelled out among the victorious western powers. The dismantled Ottoman Empire was reassembled into a puzzle of ‘nation-states’, whose subjects were destined to become ‘citizens’ once their new masters relinquished their ruling ‘mandates’. It was the gilded age of oil, and the leading international petroleum companies, having divided the world as well as the Middle East amongst them, simply ‘sat’ on their regional concessions. The end of the Second World War reset this international hierarchy, but only superficially: Britain and France retreated, relinquishing most of their petroleum holdings, while the United States and the Soviet Union, along with their own oil outfits, moved in their stead.

Nationalism and modernity seemed on the rise, and the burning question was which Middle East ruler (and oil fields) would come under which superpower. Religion was scarcely on anyone’s mind. Both superpowers believed that the supreme-God churches were waning.

But this belief was ill-founded. In retrospect, the apparent rise of secular, national forces – authoritarian or otherwise – was a thin veil that primarily mislead the foreigners. The Muslim churches remained active and religious beliefs were steadfast. Even in ‘radical’ states, such as Syria under the ‘socialist’ Ba’ath Party, the Muslim magma bubbled. [13]

The 1970s rattled the postwar oil regime. Radical terrorist groups, declaring war on Israel and the United States and challenging the entire Middle East order, captured the headlines, while the Palestinian-Israeli conflict became a key focus of international affairs. Armed Palestinian groups, with strongholds in Jordan and Lebanon, threatened air travel and promised to topple the Saudi and Jordanian royalties.

The U.S. elite, burnt by its Vietnam debacle, embarked on a new, conservative campaign to restore good old ‘American values’ and the country’s former glory. In the Middle East, Washington and its allies nourished and financed traditional movements and supreme-God churches to countervail ‘radical’ groups and Soviet-supported ‘communism’. In parallel, the region’s royal families funnelled petrodollars to madrasas and mosques to help embolden the faithful against the blasphemous American infidels and their Zionist allies.

The ‘free flow’ regime that characterized the world of oil till the late 1960s, shifted to a new, ‘limited flow’ footing, marked by energy conflicts, oil crises, petroleum shortages and rising fuel prices. While capitalism was besieged by intense stagflation, the Weapondollar-Petrodollar Coalition of OPEC, the large oil companies and leading military contractors saw its relative earnings and differential profit soar. The region’s new church wars were changing the nature of global accumulation.

Israel, which played an important role in this process, was also drifting rightward. The 1973 War, which many Israelis considered a political and military fiasco, tainted the country’s image as a modern, tolerant democracy with socialist-humanitarian roots (Horowitz 1977). The 1977 election of Menachem Begin’s Likud government exposed the colonial foundations of the state as well of the Zionist project more generally. The earlier David-versus-Goliath perception of righteous Israel standing resolutely against threats of annihilation from pro-Soviet Egypt and Syria was tarnished by the occupation and oppression of Palestinians. After the war of 1967, Israel’s Labour governments insisted that the occupied territories were temporary bargaining chips in negotiating a regional settlement. However, given their massive settlement drives in the Sinai Peninsula, Golan Heights and the West Bank and Gaza, that instance obviously was tongue-in-cheek. And it was hollowed out entirely in 1977, when the incoming radical-right government openly announced it would cleanse these areas for Jewish settlement.

And cleanse it did. By the 1980s, the Likud government had already declared 2 million dunams of Palestinian territories official ‘state lands’. Much of the confiscated areas was densely populated and often appropriated violently. The practice itself was not new, though. During the 1950s and 1960s, Labour governments routinely seized Palestinian lands within the country’s 1949 borders and expelled their inhabitants, but these acts were usually clandestine and drew little attention.

Also, Likud governments, true to their neoliberal convictions, moved to privatize the colonization. They sanctioned and financed para-military settler groups, whose role was to terrorize, scare off and expel Palestinian peasants and herders from agricultural grey zones. The vacated zones, they hoped, could then be converted to promised-land Jewish settlements.

The organization and modus operandi of Jewish settler militias resemble those of the German Freikorps. The latter, financed by rich German landlords along with American and European oligarchs, operated during the interwar period in the grey border zones between Germany and Poland. Their role was to terrorize left-wing ‘red’ organizations and destabilize the Weimar Republic. In due course, they provided the skeleton for the Nazi S.A.

But there is also a big difference. Unlike Europe’s interwar right-wing militias, which were mostly secular, Israel’s settler militias are expressly religious, staffed almost exclusively by acolytes of the Rabbinate church. Notably, this pool of religious followers was first groomed during the pre-state British Mandate period by none other than the secular Labour government in the making.

Politically, the Rabbinate church comprises two factions: one that cooperates actively with the Zionist movement, and another that (allegedly) refuses to do so, and even calls itself ‘anti-Zionist’. Theologically, the two factions are identical. They belong to the same church, follow the same rituals, rehearse the same scriptures, practice the same racism, misogyny and doublethink and await the same Messiah, whose arrival, they believe, will allow the supreme Jewish race to finally reap the gains on its long-term, risky investments. The key difference between them is their investment style. The former faction is ‘active’, seeking to intervene directly in the global redemption market to hasten the Messiah’s arrival. The latter’s stance is ‘passive’, allowing redemption market forces to equilibrate on their own.

And this difference is important. According to the redemption scriptures, the world was disequilibrated after Satan managed to separate Jehovah from his designated spouse, Shekhinah (possibly an incarnation of Anat, allegedly Jehovah’s goddess partner during the first millennium BCE; Bin-Nun 2016). The universal role of the Jews is to bring Tikkun, or ‘fix’, that will heal the fracture between the divine partners and make them copulate. By invading Canaan, killing off its inhabitants and building Jehovah’s temples, the sons of Israel helped bring this redemption a little closer. But then, their repeated betrayals of Jehovah and their prostituting with competing (false) gods, did the opposite, costing them their temple and sending them off to exile (a punishment they obviously deserved).

So, what is to be done? The answer: continue to follow Tikkun. The procedure, written secretly by Cabbala experts, stipulates that all Jews must work relentlessly to unite the godly couple. Specifically, they should follow the Rabbinate rituals to the letter, praying daily to demonstrate their guilt-ridden devotion to Jehovah and their yearning for his and his spouse’s successful sexual intercourse. [14]

According to many in the Rabbinate church, particularly in its ‘activist’ camp, the copulation of Jehovah and Shekhinah will be greatly expedited by the ‘redemption of the land’ – i.e., by expropriating, expelling and, when possible, killing the Palestine ‘gentiles’ still living in territories that the Zionists have not yet colonized, and by settling there in their stead. It is only then, with the divine couple’s orgasm, that the sons of Israel will finally be redeemed and the universe re-equilibrated (Book of Tanya, Part 1).

It is worth noting that, contrary to Israel’s early self-projections as a secular country, the roots of this messianic project predate the country’s 1948 independence. In 1947, Israel’s future prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, signed a surrender pact with the Rabbinate church. To secure the church’s future electoral support, he accepted all its demands – including the imposition of Rabbinate rituals on the country’s political regime, basic laws, army and education system. [15]

And sure enough, education, particularly since the 1980s, was made decreasingly secular and liberal, loaded with more and more church scriptures and increasing doses of patriotism. The result of this process was a fundamental change in Israeli society. Nationalism gradually fused with church-promoted racism – to the point that many ‘secular’ Israelis have become de-facto followers, however incognisant, of the Rabbinate-nationalist church.

The 1980s also saw the emergence of new radical-right political parties. The first batch of parties offered pure-race platforms. The second round, founded mostly by retired generals, glorified the Jewish ‘homeland’ and called for the ‘transfer’ of Palestinians. Then there were those that, inspired by the radical European right, catered to Russian immigrants and ended doubling as Likud satellites. All of them attracted religious supporters, particularly settlers from the occupied territories.

The single most important inspiration for these parties was Kach, a racist Rabbinate party founded in the early 1970s. Its founder, Meir Kahane, was a U.S. convict and former undercover FBI mercenary, assigned, among other tasks, with demoralizing leftwing groups that protested the Vietnam War. [16] His party, which marshalled a Talmudic platform retrofitted to the capitalist state, was condoned by the authorities but remained marginal. In the longer run, though, Kach’s platform, practices and activists served to define the political culture of Israel’s radical right and accurately foreshadowed its rise to power.

In 2022, the ‘active’ and ‘passive’ factions of the Rabbinate church finally united in a heavenly, Likud-led coalition headed by Benjamin Netanyahu. The members of this coalition call it the ‘full-fledged right’. In their eyes – as well as in the eyes of their anti-Zionist critics – Zionism has finally been realized.

The radical Islamic churches, too, have been revived. The watershed was 1978. Ayatollah Khomeini took over Iran, and following his victory, the old supreme-God churches, tweaked to the new technologies of power, retook the Middle East.

The protagonists remained the same: the Suni church with its Wahhabi National Guard militias under the auspices of the royal Saudi family versus the Shia church and its Revolutionary Guards of the Iranian Ayatollahs. Both churches reimposed their rigid rituals on their subjects, rekindled old conflicts with sworn adversaries and broadened their holy wars against new foes.

In 1979, Syrian Suni clerics with royal Saudi financing mobilized the Muslim Brotherhood militias against the brutal repression of the Alawi Ba’ath apparatus. The rebellion, which was probably inspired by the successful revolution in Iran, lasted until 1982, mainly in the cities of Aleppo and Hama, and was suppressed only after an estimated 50,000 people were killed. In a widely circulated communique, the Alawi oligarchy announced that ‘the regime was ready to kill a million Syrians in order to defend “the revolution”’ (Ajami 2012: 40). The rebellious Muslim militias retorted with an ominous quote from 14th‑century theologist Ibn Taymiyya: ‘Their religion externally is Shiism but internally it is pure unbelief’. Ibn Taymiyya’s fatwas against the Alawites (Nusayrites) marked them as apostates, enemies of Islam to be exterminated and dispossessed (Ajami 2012: 17).

The next round started in 2011, as part of region-wide protest (labelled by Western journalists as the Arab Spring). The revolting Syrian militias were again financed by Saudi Arabia, as well as some of the Gulf emirates – but this time, the human toll was much higher, estimated at more than half a million dead and 5 million refugees.

Afghanistan, too, joined the cycle of uprisings. In 1979, its Suni militias, initially supported by the United States, rose against the country’s secular administration which attempted to impose Soviet-style ‘modernisation’. Seemingly indifferent to their own heavy losses, the rebels sustained a brutal, decade-long war, killing at least 15,000 Soviet soldiers, defeating and expelling the Soviet army, taking over the capital Kabul and imposing their radical sharia on their country’s subjects.

In 2001, Al-Qaeda, a Suni militia with close ties to the Saudi royal family, claimed responsibility for blowing up the World Trade Center as well as part of the Pentagon and for murdering 3000 Americans. A U.S.-led coalition retaliated by invading Afghanistan and Iraq (the Second Gulf War), which in turn triggered a new flurry of militia conflicts and takeovers across the region, including in Iraq, Syria, Pakistan and Afghanistan.

It took Afghanistan twenty years to expel the U.S.-led army of infidels, but the victory seemed bitter. The triumphant country was globally isolated and suffered a severe humanitarian crisis. But that did not seem to bother its supreme leader, Hibatullah Akhundzada. On the contrary. Celebrating Eid al-Adha, the Taliban chief sent his hungry subjects a stern warning: ‘We were created to worship Allah and not to earn money or gain worldly honor [. . . .] We have promised God that we will bring justice and Islamic law (to Afghanistan) but we cannot do this if we are not united [. . . .] [T]he enemy takes advantage of it’ (Anonymous 2024b).

Israel’s radical right militias seem equally steadfast. They have openly fused with the Rabbinate church, coalesced with Netanyahu’s neoliberal government, captured key strongholds in their country’s military, security services and government apparatuses, intensified the half-century occupation of Palestine and helped further radicalize the Palestinian resistance. Their messianic endgame is firmly on track.

The net result is a richly financed, well-publicized confrontation between two resolute and heavily armed militias, backed by mutually hostile supreme-God churches that vow, God willing, to never give up. Amen.

Endnotes

[1] Shimshon Bichler teaches political economy at colleges and universities in Israel. Jonathan Nitzan is an emeritus professor of political economy at York University in Toronto. All their publications are available for free on The Bichler & Nitzan Archives (http://bnarchives.net). Research for this article was partly supported by SSHRC.

[2] Steven Pressfield’s thriller, The Profession (2012), describers a not-so-distant future, in which giant mercenary armies complement and cooperate with traditional national armies by offering services to both corporations and governments, including illegal and politically incorrect activities that nation-states prefer to avoid. Gradually, these mercenary armies alter the nature not only of international relations, but of the nation-state itself.

[3] A comparative study of 414 societies in 30 different regions over the past ten millennia, showed that ‘big gods’ tended to emerge together or after – but not before – a significant increase in social complexity (Whitehouse et al. 2019).

[4] ‘Who may comprehend the mind of gods in heaven’s depth? The thoughts of a god are like deep waters, who could fathom them?’ asks a Sumerian epos (quoted in Frankfort et al. 1946: 215). And the clerics kept the veil ever since: ‘who does great things and unsearchable, marvelous things without number’ (Job 5: 9); ‘The Lord is the everlasting God, the Creator of the ends of the earth […] his understanding is unsearchable’ (Isaiah 40: 28); ‘O man, who art thou that repliest against God?’ (Romans 9: 20).

[5] And why would the ‘children of Israel’ submit to Jehovah? Simple. Jehovah freed them from their prior enslavement to the king-priests of the Egyptian temple, so obviously, he was entitled to enslave them in turn to the king-priests of his own temple in Jerusalem (Book of Leviticus 25: 55). Elsewhere in the bible, the ‘children of Israel’ appear as Jehovah’s wife, which was hardly better than slavery: ‘I will betroth you to me in faithfulness. And you shall know the Lord’ (Hosea 2: 20); ‘I remember the devotion of your youth, how as a bride you loved me and followed me through the wilderness’ (Jeremiah 2:2). When botched military campaigns ended in mayhem and destruction for the ‘children of Israel’, the blame was laid squarely on the suffering devotees. They were being punished for committing adultery and whoring with other male gods, for violating their marriage ‘contract’ with Jehovah, for defaming their family’s honour, for breaching the one-sided exclusivity-deed the temple priests signed on their behalf, etc. (Hosea, 1‑3). For a concise summary of the Jehovah rituals in eighth- and seventh-century BCE Jerusalem, the imposition of these rituals on the local population and the ways in which they helped bond the royal dynasty and temple priesthood, see Bin-Nun (2016).

[6] Jesus’ reincarnation as the Messiah son of David is stipulated in the Gospel of Matthew (1). For a summary of his transmutations, see Fredriksen (2018: Ch. 4).

[7] One of the major victories of Europe’s secular-liberal revolution was lowering the bourgeoisie’s birth rate. This reduction was a major setback for the old mode of power (and later also for capitalism). It forced rulers to roam the globe in search of cheap, submissive and rapidly reproducing subjects to replenish their ever-hungry megamachines.

[8] The official reason for this practice is an alleged covenant between Jehovah and a Mesopotamian fellow named Abraham, who ran a security service for commercial and royal convoys. At Jehovah’s behest, the secret deal stipulated that Abraham, his clan’s males and all their male descendants and slaves for ever after, remove their foreskin and serve Jehovah (read, his clergy) in return for some unspecified future services (Genesis 17: 10-14).

[9] Female submissiveness was preached already by the Christian apostles: ‘Wives, in the same way submit yourselves to your own husbands so that, if any of them do not believe the word, they may be won over without words by the behavior of their wives’ (First Epistle of Peter 3: 1). The Protestants elevated misogyny to pathology. According to Martin Luther, ‘No good ever came out of female domination. God created Adam master and lord of all living creatures, but Eve spoiled all’ (Starr 1991: 185). Among Jehovah’s settlers, women fared worse than in the sun empires: ‘If […] no proof of the young woman’s virginity can be found, she shall be brought to the door of her father’s house and there the men of her town shall stone her to death. She has done an outrageous thing in Israel by being promiscuous while still in her father’s house’ (Deuteronomy 22: 20-21). Of course, ‘If a priest’s daughter defiles herself by becoming a prostitute, she disgraces her father; she must be burned in the fire’ (Leviticus 21: 9). In Talmudic writings and those of ‘philosophers’ like Maimonides, women are totally subjugated to men, who are in turn entrusted with maximizing their output of future god’s servants (Talmud Bavli, Nedarim 20b: 4, 6; Talmud Bavli, Sotah 26b; Rambam, Mishneh Torah, Forbidden Intercourse 21: 1, 11, 18). As for the Muslim church, here is how the Quran explains Allah’s divine logic on the subject: ‘Women have rights similar to those of men equitably, although men have a degree of responsibility above them. And Allah is Almighty, All-Wise’ (Surah 2: 228) ‘Men are the protectors and maintainers of women, because Allah has given the one more (strength) than the other […] the righteous women are devoutly obedient […] As to those women on whose part ye fear disloyalty and ill-conduct, admonish them (first), (Next), refuse to share their beds, (And last) beat them (lightly); but if they return to obedience, seek not against them Means (of annoyance): For Allah is Most High […]’ (Surah 4: 34).

[10] In 2024, there were 230 million girls and women worldwide who underwent genital mutilation (UNICEF 2024). Most are in Africa, Asia and the Middle East. In Egypt, for example, the proportion is 87%. See also Hirsi Ali (2007) and Saadawi (2024). For some reason, estimates of the global number of females murdered for allegedly dishonouring their family remains elusive. Fisk (2010) approximates it at over 20,000 annually.

[11] For the Rabbinate version, see, for example, Sanhedrin 82a; Sefer HaChinukh 347: 1; Rambam, Mishneh Torah, Kings and Wars 8: 3.

[12] In the United States, where monotheism remains strong, the overall proportion of church membership dropped from 73% in 1937, to 45% in 2023 (Anonymous 2024a), while the proportion of those believing in a single, supreme god declined from 95% in 1945, to 75% in 2023 (Anonymous n.d.).

[13] Bernard Lewis tells the story of a Second Lieutenant in the Syrian army, a Ba’ath-party enthusiast, who, in 1967, published a paper in an army magazine, which he titled ‘The Means of Creating a New Arab Man’. The only way to build Arab society and civilization, the officer posited, was to create

a new Arab socialist man, who believes that God, religions, feudalism, capital, and all the values which prevailed in the pre-existing society were no more than mummies in the museums of history [. . . .] There is only one value: absolute faith in the new man of destiny [. . .] who relies only on himself and on his own contribution to humanity [. . .] because he knows that his inescapable end is death and nothing beyond death [. . .] no heaven and no hell [. . .] We have no need of men who kneel and beg for grace and pity [. . . .] (Lewis 1993: 5)

Popular reaction to the article was swift. The underlying Syrian population, normally indifferent to politics and scared of the Ba’ath party’s ruthless dictatorship, was flabbergasted by this open assault on Allah and his rituals. The ensuing demonstrations threatened the regime, and within less than two weeks, the author and magazine editor, blamed for collaborating with the CIA, British, Jordanians, Saudis and Zionists, among others, were prosecuted and sentenced to life imprisonment.

[14] Most daily rituals of the Rabbinate church are preceded by reciting the following cabbalistic text: ‘For the sake of the [sexual] congress of the Holy Blessed One and his Shekhinah’ (among other encouragements). Since the prayer is written in disrupted Aramaic, the supplicants rarely if ever understand what they wish for (for details and sources, see Shahak 1994: 39-41).

[15] Mainstream historians dub this the ‘status-quo agreement’, but that label is deeply misleading. These were not existing, but new arrangements. Simply put, Ben-Gurion’s pact was a pre-emptive, (anti)judicial coup.

[16] Hitler, too, arrived in Germany as an Austrian fugitive, where he began his political career as a mercenary for capitalist-financed right-wing militias, trying to demoralize and destabilize left-wing political parties in Munich.

References

Anonymous. 2015. Losing Our Religion? Two Thirds of People Still Claim to Be Religious. June 8. Gallup International.

Anonymous. 2024a. How Religious Are Americans? Gallup, March 29.

Anonymous. 2024b. Reclusive Taliban Leader Warns Afghans Against Earning Money or Gaining ‘Worldly Honor’rel. AP.

Anonymous. n.d. Religion. Gallup.

Bichler, Shimshon, and Jonathan Nitzan. 1996. Putting the State In Its Place: US Foreign Policy and Differential Accumulation in Middle-East "Energy Conflicts". Review of International Political Economy 3 (4): 608-661.

Bichler, Shimshon, and Jonathan Nitzan. 2015. Still About Oil? Real-World Economics Review (70, February): 49-79.

Bichler, Shimshon, and Jonathan Nitzan. 2018. Arms and Oil in the Middle East: A Biography of Research. Rethinking Marxism 30 (3): 418-440.

Bichler, Shimshon, and Jonathan Nitzan. 2023. Blood and Oil in the Orient: A 2023 Update. Real-World Economics Review Blog, November 10.

Fisk, Robert. 2010. The Crimewave that Shames the World. Independent, September 7.

Fix, Blair. 2022. Have We Passed Peak Capitalism? Economics from the Top Down, July 7, pp. 1-41.

Hirsi Ali, Ayaan. 2007. Infidel. New York: Free Press.

Horowitz, Dan. 1977. Is Israel a Garrison State? Jerusalem Quarterly (4 (Summer)): 58-75.

Nitzan, Jonathan, and Shimshon Bichler. 1995. Bringing Capital Accumulation Back In: The Weapondollar-Petrodollar Coalition -- Military Contractors, Oil Companies and Middle-East "Energy Conflicts". Review of International Political Economy 2 (3): 446-515.

Nitzan, Jonathan, and Shimshon Bichler. 2009. Capital as Power. A Study of Order and Creorder. RIPE Series in Global Political Economy. New York and London: Routledge.

Pew Research Center. 2015. America’s Changing Religious Landscape (May 12).

Pressfield, Steven. 2012. The Profession. A Thriller. 1st ed. New York: Crown.

UNICEF. 2024. Female Genital Mutilation: A Global Concern. 2024 Update. New York: UNICEF.